Several years ago I watched a documentary on the Apartheid in South Africa during Denver’s Film Festival. I have spent time in South Africa and love the country. I have seen Mandela’s cell in the prison on Robben Island. I have been to Soweto and the museum in Johannesburg and listened to the stories. Though the film revisited many of these places, I actually recall very little of it except for the story of one man. He had a position in the South African government that supported and benefitted from the apartheid, the system of legislation that enforced severe racial segregation. He was also a Christian.

What I do remember of the film was his ache. “I didn’t see, I didn’t see,” he cried. Tears of repentance and lament dimmed his eyes as he described his awakening to the suffering and humiliation imposed on black South Africans by the privileged white regime. His lament is one that I hope and pray will be the cry of many white Americans as we slowly awaken to the reality of the experience of black people in America.

We simply don’t see. It is extremely difficult for white American Christians in particular to recognize our racism. We don’t like this word. We react to this word. But to move towards healing, we need to face this word. It’s not that most of us would ever wish misfortune upon a person of color, nor would many of us knowingly treat a person of a different race insensitively. Most of us just go about our lives, trying to be nice. And comfortable. And happy.

We simply don’t see.

We have a built in defense against seeing our complicity in the painful realities of the lives of those who are not white in America. We have created a church culture in which any sense of darkness, failure or just plain selfishness in ourselves is too shameful to admit. We have learned to cast the yuckiest parts of ourselves into shadow so we can present what is manageable and attractive. It is not uncommon to hear people talking about “what the Lord has been working on in me.” But it’s rare to hear the real humility of simple honesty: I am both saint and sinner, glorious and grotesque. And sometimes I’m just a jerk. I’m afraid. I get nervous when walking past a black man I don’t know. I assume that if a cop shoots a black man then he must have been guilty. “They” struggle because “they” don’t work hard enough. We don’t admit these things out loud very often. We are too practiced at presenting ourselves to be better than we actually are, and so we are not transformed in the deep places.

We don’t understand what life is like living in a black body in this nation. We simply can’t understand why “they” can’t just be like “us.” We don’t understand systemic injustices. We don’t realize that we judge others’ experiences and complaints and sufferings through the lens of our own lives and opportunities and presumptions. We don’t see that white lives are very privileged, which means that everything is tilted in our favor. We rarely meaningfully interact with people who struggle to survive underneath our society’s oppressive heel. We don’t see that we all have an innate suspicion of the other. We simply don’t see that we are deeply racist because we are deeply human.

It will be costly to learn to see through the eyes of the other. But it doesn’t start with scolding. It starts with love. Our faith brings us face to face with the gaze of Love. Most often we turn from its penetrating brightness. But once the light of that love has illuminated our hearts, we can begin to see others with new compassion. We can see ourselves with that compassion too, and be less fearful of seeing the ugly things we haven’t wanted to see. Encountering this Love is way of healing. It lifts the logs from our eyes and we see anew. It is the way of Christ.

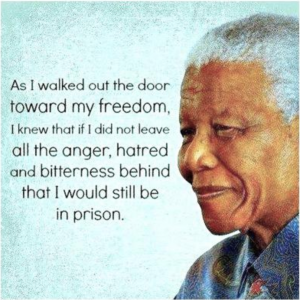

Nelson Mandela knew such love. He was imprisoned for 27 years for opposing a regime whose apartheid laws constitutionally entrenched the humiliation and condition of de facto slavery for South African blacks. He was considered a terrorist. However, he spent his imprisonment learning Afrikaans, the language of his white captors and over time he won their respect. He read their books, and their poetry. He knew their souls. He created relationships through which he entreated the prison guards to treat him as a fellow man – one with human dignity. When he was released he treated everyone, including his former enemies, with the same respect and dignity that he had engendered for himself. He had fought white domination and therefore refused to allow black domination. He was a master reconciler; he persuaded a whole people, in this case the most racially divided people on Earth, to change their minds towards one another.

After Mandela’s release and the dismantling of apartheid law, the ANC (African National Congress) party was certain to win the first democratic election in South Africa in 1994. Nelson Mandela would become the President of South Africa. The party faced the small problem of deciding what would be the new national anthem for an essentially new nation. The old anthem celebrated the advance of white colonizers as they crushed black resistance. The unofficial anthem of black South Africans was a soulful, heartfelt tune about their longsuffering. It was gleefully clear to the new committee that the official white anthem was out. Mandela responded however, “This song that you treat so easily holds the emotions of many people who you don’t represent yet. With the stroke of a pen, you would take a decision to destroy the very – the only – basis that we are building upon: reconciliation.” He had spent 27 years getting to know the heart of those who had been his enemies. He taught that you win over people by respecting their symbols and all that is deeply meaningful to them saying, “You don’t address their brains, you address their hearts.” Eventually they pulled together two anthems in five languages into one united song.

And slowly, gently, hearts were changed, like that of the weeping Christian man in the documentary. “I was blind and now I see,” he cried. Hearts were transformed because someone listened, learned, and opened himself to the other. Mandela refused to ever compromise on the dignity of the human person no matter what color, political stance or religion. Some in the former apartheid regime feared a reverse apartheid. Instead, Mandela learned their stories, he listened to their souls, and he honored their lives. He crossed over into the reality of the other. And a nation healed.

May it be so for us, America. We have been graced with the light of God’s love and the hard won wisdom of this teacher who helps to illuminate our darkened path.

The Light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it. (JN. 1:5)

“I once asked Archbishop Desmond Tutu, a Nobel peace prize winner like Mandela, and one of the people who knew him most intimately, if he could define Mandela’s greatest quality. Tutu thought for a moment and then – triumphantly – uttered one word: magnanimity. “Yes,” he repeated, more solemnly the second time, almost in a whisper. “Magnanimity!”

There is no better word to define Mandela. No leader more big-hearted, more regal, more generously wise. Not now and, quite possibly, not ever.” ~John Carlin

Mandela was a reader. Some books that help with learning and listening include: Disunity in Christ by Christena Cleveland, Divided by Faith by Emerson and Smith, The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander, Just Mercy by Bryan Stephenson, Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates, and the many powerful novels by Toni Morrison.

[This has been reposted, originally from Nelson Mandela Day 2016]

For more posts about Nelson Mandela:

- Every Heart Beats in Every Chest – Nelson Mandela Day by Jenneth Graser

- Thank You Nelson Mandela by Rowan Wyatt

- A Liturgy of Remembrance for Nelson Mandela by John Van de Laar

- A Tribute to Nelson Mandela – Quotes that Inspire Me by Christine Sine