by Louise Conner, originally posted on the Circlewood blog The Ecological Disciple, here: The Art of Creation: Safe Passage

In the effort to provide safe passageways for all kinds of mammals, fish, crustaceans, and turtles, to name a few, wildlife corridors in all shapes, sizes, and locations are being built so creatures can move safely through areas which could otherwise be hazardous to them. These corridors pass over railroad tracks, under freeways and sometimes, as in today’s post, through an entire city, as they attempt to mitigate the danger that human structures can be to the wild creatures living in the neighborhood.

The Oslo Project

In 2015, BiBy, a beekeeping group in Norway, created a different kind of wildlife corridor, a “Pollinator Passage,” which helps pollinators find safe passage amidst the city streets of Oslo, Norway. Worldwide, pollinators are suffering from a decrease in the habitat they depend upon. Finding a safe pathway is particularly a problem for pollinators in large cities, where pavement is more plentiful than flowers and where even green space doesn’t necessarily provide the nutrients and safe haven that pollinators need (particularly if the green space consists of monocultural lawns or non-native plants, or if pesticides which are harmful to pollinators are used).

Meadows are an optimal feeding grounds for bees and other pollinator insects because of the wide variety of flowers within them. The variety of pollen and nectar produced in a meadow provides for different types of pollinators, and the rotating bloom of different flowering species provides sustenance throughout the season. But meadows are being lost as areas are cultivated or paved over, and are particularly rare in large urban areas.

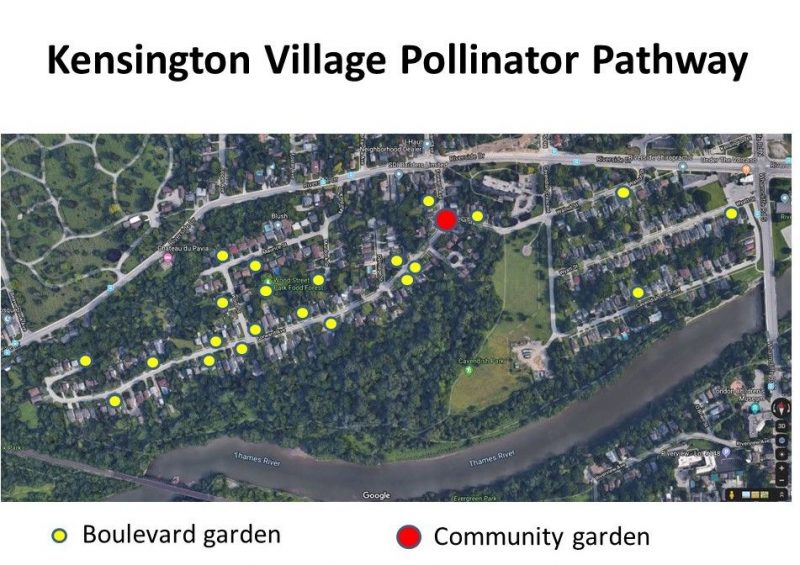

Since most people in the city don’t have the ability to plant an entire meadow, the Oslo pollinator passage works by creating a pathway of flowers from one person’s patio to another’s yard, one yard to another window box, a window box to a local cemetery, a cemetery to a rooftop, the rooftop to a city garden, one leading to the other, creating the equivalent of a meadow pathway through the heart of Oslo. Through coordination, the separate pieces come together into an amazing whole.

Strategic planting and placement of flowers grants pollinator insects’ migration paths and easy, accessible food as they make their way across the city without the stress of being unable to find the food they need. Government, private businesses, and individuals all joined the work in building this highway, making it possible to achieve the results with no one person or group having to use massive resources. With many individuals and groups joining in with small and large contributions, in their particular location in the city, a pathway beyond what any could have accomplished by themselves was created.

Although the soil needs to be cultivated and maintained with good growing practices to develop the pollinator passage, it is still relatively inexpensive, especially since most of the flowers that support wildlife are technically weeds. Once they are planted, being native “weeds,” they require little care since they are already well adapted to the environment in which they find themselves.

In addition to plantings, appropriate housing for the pollinators was also a need in Oslo. Different species of bees for instance, have different housing needs. While honeybees live primarily in man-made beehives, solitary bees prefer cavities in dead wood or nests in sand and soil; bumblebees like bumblebee boxes, mouse-hole-type constructions. Discarded snail shells or flowers with the heads upside down are also ideal rest stops for some types of bees.

Two of the most impressive beehives in Oslo were designed by the same person who designed the Oslo Opera House; they are found on top of Dansens hus in the Vulkan neighborhood.

The main instigator of the Oslo pollinator passage, Agnes Lyche Melvaer, points out that it is not so much the honeybee that most needs these pollinator pathways. Bees are most fragile in early spring, when they’re weakened from winter. “Honeybees can normally fly very far; they are living in societies with hundreds of thousands of members and have to fly very far to find food, but solitary bees only fly a few hundred metres, and they have to find all that food in a small radius. So, we have to connect landscapes for the solitary bees, so they are not living in isolated islands.”

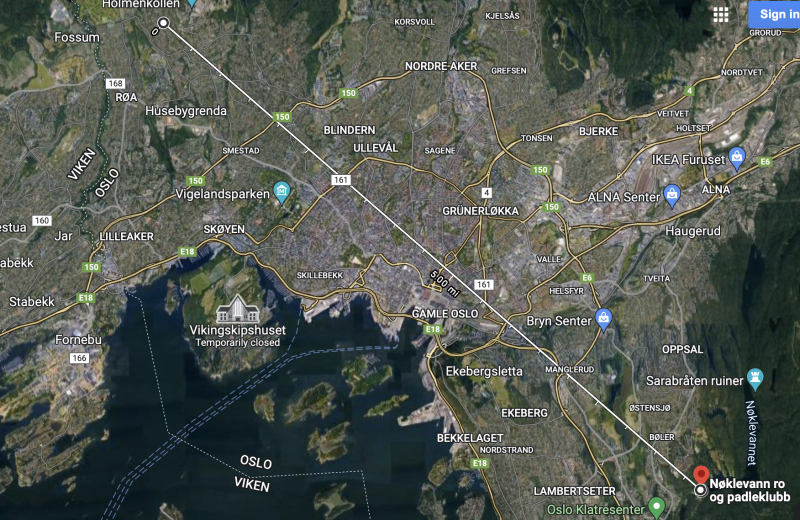

The “pollinator passage” of Oslo reaches from Holmenkollen in the northwest, to Lake Nøkkelvann in the southeast. As you can see from the satellite map below, it passes right through the center of Oslo. Green roofs, lush parks, and strategically placed beehives make it possible for the pollinators to find resting places and food almost anywhere in the city; dead spots have been pretty much eliminated from this pathway as participants have filled in the needed links along the way with their contributions to the project.

Beyond Oslo

The concept of the pollinator pathway has spread far beyond Norway as other communities and environmental groups have embraced the concept. The publicized Colony Collapse Disorder has alerted people to the importance of pollinators, although this has also caused some dissent and misunderstanding with what many believe is a misplaced emphasis on honeybees. More significant native pollinators are often overlooked with all the attention going to the non-native honeybee.

This point is made often and strongly by Sarah Bergmann of Seattle, Washington, who was an early developer of the Pollinator Pathway in that city. As people have become more aware of the threat to pollinators and the importance of their survival, examples of pollinator pathways have become more numerous, spurring even more cities, states, and even entire countries to develop their own pollinator pathways. Many cities in the U.S. have pollinator pathways projects; and some countries have set far reaching goals for such projects—the United Kingdom’s B-Lines being an example.

The beauty of these pathway projects is that even a single individual can make a valuable contribution to the effort and by connecting the plots and pots together, these benefit just get more amplified.

For those who want to plan and organize a project like this in their own community, there are many examples to learn from and even downloadable resources to help guide a person through the planning and implementation, such as this one from Sarah Bergmann.

As Melvaer says, she has faith in the “butterfly effect,” believing that, “If we manage to solve a global problem locally it’s conceivable that this local solution will work elsewhere too.”

Reflection Questions: If you have flowers in your yard, do you know what percentage of them are native plantings? Is the area around you “pollinator-friendly”? Is there a way you could make it more so?

You may contact Louise at info@circlewood.online

Whatever season your garden is in – winter, summer, spring, or fall – there is something to enjoy and tasks to accomplish. And there is spirituality to put into practice! Find God and community through the richness of soil and the shared values of growth. We have many resources available to help – click here to explore!

Whatever season your garden is in – winter, summer, spring, or fall – there is something to enjoy and tasks to accomplish. And there is spirituality to put into practice! Find God and community through the richness of soil and the shared values of growth. We have many resources available to help – click here to explore!