by Greg Valerio

PREPARED TO BE IN COMMON WITH THE CROWD.

BE ALONE IN A SEPARATE PLACE NEAR A CHIEF CITY, IF YOUR CONSCIENCE IS NOT

There can be no doubt that the Celtic Saints knew how to choose a location and be alone with God. Aidan’s Lindisfarne, Cuthbert’s Inner Farne, Kevin’s Glendalough, the disciples of Dicuil’s Bosham or Columba’s Iona are places that are inhabited by a true sense of the wild, the wonderful, the dramatic and the intensely beautiful. They were on the very edge of where humanity at the time could exist. The sensory overload you experience when standing in such locations is truly majestic. I have always been struck by what overwhelming instinct would drive ordinary men or women to abandon the shelter of their homes and warmth of their partners beds to journey to the edge of the known world and live out a sparse and meagre existence. Nowhere in Britain and Ireland is more exemplary of this than the wild and exposed monastic rock of Skellig Michael, resting as it does, in the arms of the wild Atlantic and its Creator.

What is immediately recognizable when you begin to read Columba’s rule was that he placed the location of our encounter with Christ before the ‘naked imitation of Christ (rule 2)’. The more we reflect upon the location of our encounter with The Trinity, the more we can begin to appreciate the simple logic in this, as well as the profound impact that such a step could have in our lives.

Alone and separate does not mean lonely and isolated. There can be no doubt that to embrace the idea of being alone, can be a terrifying experience for many people. Walking away from the noise and bustle of modern society and the sense of self-importance derived from eating at this table, is an intentional step that is extremely counter intuitive in society and conventional church culture. The daily activity of modern life bombards ones senses with images, noises and activities, that in the final analysis, are questionable regarding how aligned they are to ones eternal reality.

‘If you belonged to the world, the world would love you as one of its own. Because you do not belong to the world, but I have chosen you out of the world-therefore the world hates you.’ John. 15:19. To intentionally remove ones self from the world’s narrative is a bold step for anyone. A simple objective, yet complex to execute. One of Our societies primal tools used to keep us wedded to the worlds system is fear and desire. It is fascinating to reflect upon the crude nature of advertising as an illustration of this. Its

* Desire to possess what we do not have or need,

* Fear of what may happen to us through what we cannot see or control,

* Ownership of a product that will satisfy the desire or alleviate the fear.

All this gives us the illusion of being in control over the natural order through domesticating of the world

Being separate and alone moves us to a place where we have to live with our own inner turmoil, conversations, fears and desires without the soma of modern living that drowns out the voice of our true selves. Finding that place is not easy. For St. Columba and his many followers this was the first step. Find your space, find your location, find your stillness, find your place where you can be alone with the Trinity.The pursuit of Columban spirituality is not just a practice of personal stillness and prayer, it equally involves discovering, with the Creator, that place that embodies the dynamism, drama and breadth of the encounter of the living Christ. The Columban charism is not cloistered, it is always seeking those places of liminal exposure in the landscape. This extract from the Columcille Fecit beautifully illustrates this point, St. Columba locates himself on a promontory, from where he can participate in creations conversation,

‘Delightful would it be to me to be in Uchd Ailiun,

On the pinnacle of a rock,

That I might often see,

The face of the ocean;

That I might see its heaving waves

Over the wide ocean,

When they chant music to their Father

Upon the world’s course’.

Naturally this practice takes on many shapes and forms. It can be a location, it can be a meditative state that opens one up to the eternal presence, it can be an iconoclastic image that triggers humility. Yielding to the ‘aloneness’ of self, ushers in the face of Christ in whom we encounter our true identity. It is here we are discovered and discover that we are never alone. The opening phrase of the Rule of Columba begins to capture the true kernel of what the indigenous Christian spirituality of the British Isles is all about. The yearning for intimacy with Christ in the total abandonment of self to love and passion of the Godhead. This can only be experienced through naked intimacy (one cannot be intimate in public after all, as society and institutionalised religions, classes that as indecent).

Yet this aloneness and the richness that flows from it is also set in an eternal location. The inner journey is captured in harmony with the created order. For the monastics of Britain this creational journey had to be remote, wild, exposed and inhabited by our presence with God alone. Creation it would seem is the cathedral of our worship. In the world of God’s Spirit intimacy means naked exposure, for example, the Psalmist could only capture the depth of God’s presence through the experience of being overcome by the power of water.

‘As deep calls to deep, at the thunder of your cataracts:

And all your torrents, all your waves have flowed over me’. Psalm. 42:7.

St. Columba understood that aloneness meant ‘togetherness without distraction’ and that the creation was

the bed upon which we lie down with the Godhead. As we are enfolded in the dynamic personality of the

Spirit, the immanence of Gods-self in the wonder and beauty of the created order will enable us to enjoy

the nature of our true selves.

By Andy Wade –

Many of you know that I’ve transformed our backyard into a food garden sanctuary. It’s not big, but it’s bountiful! It’s also where I sit and listen, work and listen, and graze and listen, to the voice of God.

Our Godspace Community theme this month is “Listening to the Celtic Saints” and, although this post isn’t about any particular Celtic saint, it carries within it the deeply Celtic understanding that nature itself is a testament to God. Saint Columbanus once said, “If you want to know God, first get to know his creation.”

When I go into my backyard sanctuary I carry with me the joys and concerns encountered in the world around me. I am not cut off from them but actually become more aware of their impact on my life and my interconnectedness with all that buzzes in and around my world.

When I plunge my hands into the earth I’m reminded of my connectedness to all creation. God formed me from the richness of the soil and breathed life into me. Like all creation, I am alive and sustained only by the grace of God.

When I plunge my hands into the earth I’m reminded of my connectedness to all creation. God formed me from the richness of the soil and breathed life into me. Like all creation, I am alive and sustained only by the grace of God.

Norman Wirzba, in his book Food & Faith: A Theology of Eating, speaks eloquently about the interconnectedness of all creation. God’s whole system of creation is based on sacrifice and interdependence – for something to live, something else must sacrifice and die. The entire web of life created by God is sacrificial at its core.

So even when I’m alone in my backyard, I am not truly alone. This is not a place of escape but of understanding more deeply my part in this web of life. This is a place where God cultivates my heart and prunes my mind so that I may bear good fruit to share with the world around me.

Likewise, when I venture into the front yard, or into the larger community, I carry with me the still small voice of God experienced in the backyard sanctuary. If I have listened and learned well, the community is where I put these lessons into practice. If, instead, I keep my life segregated into private/spiritual and public/secular, I will simply reap a harvest of hypocrisy.

No matter your diet, something has to die for you to eat. Something has to sacrifice its life so that we can live – be it plant or animal. This profound lesson is often lost on us as we head off to the grocery store or sit down in a restaurant. All of life, and all of living, is built on sacrifice.

No matter your diet, something has to die for you to eat. Something has to sacrifice its life so that we can live – be it plant or animal. This profound lesson is often lost on us as we head off to the grocery store or sit down in a restaurant. All of life, and all of living, is built on sacrifice.

You can take this lesson even further and realize, even if you grow all your own food, you’re still connected to the world around you:

-

Will you cook your food? Where does the gas, electricity, or wood to cook it on come from?

-

How about the appliances and utensils used to cook it?

-

What about the dishes, the silverware, the table, and the chairs?

It’s easy for us to forget just how interdependent we are. And when we forget the sacrifice of others so that we might eat — the harvesters, the growers, the transporters, those who store the food, the grocery store employees, and on and on — when we forget about all these important people in our lives, we too easily forget to give thanks for all they’ve made possible.

In the letter to the church in Rome, the Apostle Paul purposefully includes creation’s role in God’s plan. Listen to these words in Romans chapter 1:18-20:

The wrath of God is being revealed from heaven against all the godlessness and wickedness of people, who suppress the truth by their wickedness, since what may be known about God is plain to them, because God has made it plain to them. For since the creation of the world God’s invisible qualities—his eternal power and divine nature—have been clearly seen, being understood from what has been made, so that people are without excuse.

It’s easy to read these words and simply focus on God’s wrath and judgment, failing to see that behind those words lies an important truth: God’s creation also gives testimony to the reality and glory of God.

Later, in Romans chapter 8:19-23a (NLT), Paul goes on to speak directly to the connection between humankind and the rest of creation:

For all creation is waiting eagerly for that future day when God will reveal who his children really are. Against its will, all creation was subjected to God’s curse. But with eager hope, the creation looks forward to the day when it will join God’s children in glorious freedom from death and decay. For we know that all creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. And we believers also groan, even though we have the Holy Spirit within us as a foretaste of future glory, for we long for our bodies to be released from sin and suffering.

God’s creation is not somehow separate from God’s plan of redemption but woven right into the fabric of God’s overall design! When we forget this, we easily take for granted God’s gift of creation and our call to steward it as an act of worship and obedience. When we forget that God’s very good creation also gives testimony to God, we can begin to think that it’s ours to trample on, ours to exploit, and ours to use for our own selfish purposes.

But no, creation too is part of God’s plan and part of its testimony of God is the reminder of sacrifice. Even the plants in our garden require sacrifice to live. Dying plants and animals feed the soil that nourishes the new, emerging plants.

In the very simple act of eating, God demonstrates for us that all of life is connected and all of life is sacrifice. For this reason, in the season of Lent we are reminded that we are dust, we are soil, mud of the earth, and to the earth we shall return.

Jesus’ words should not surprise us then, radical words like:

-

This is my commandment, that you love one another. There is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.

-

Whoever wants to save her life must lose it.

-

By this we know what love is: Jesus laid down His life for us, and we ought to lay down our lives for one another.

-

At just the right time, when we were still powerless, sinful, broken, enemies of God, Christ died for us. Very rarely will anyone die for a righteous person, though for a good person someone might possibly dare to die. But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us. AND…

-

Take up your cross daily and follow me.

SACRIFICE. God built it into creation and calls us to enter into this rhythm of life and death with joy. But it’s also much bigger than that. Going clear back to the fall, to Adam and Eve’s disobedience in the garden, we learn that broken relationships are costly.

Hiding in the bushes, ashamed and not wanting to come face to face with God, God calls them out. Although they had fashioned fig leaves in an attempt to cover their “nakedness”, their shame, God chooses to clothe them with animal skins. Even here, at the beginning of the story of God and creation, we discover death, sacrifice, as a means to deal with our brokenness.

So we have God’s naturally created order with a deep, deep interdependence of all creation built on a system of self-sacrifice; for something or someone to live and thrive, something else must die. And when relationships are broken, when we step outside the shalom-order of God, an even greater sacrifice is required.

Perhaps the most profound place we discover this connection is at the Communion table. Simple elements of bread and wine, fruit and grain harvested, “sacrificed”, for our sustenance while at the same time representing on a level almost too deep to understand the body and blood of our Lord given for us that we might live.

As we gather around this table and share this bread and wine, the fruit of creation, we are the body of Christ. Together we join with Columbanus and all the saints, the whole community of faith past, present, and future, and become one. Here we are nourished. Here we receive life. Here we both embrace the sacrifice of Christ for us and enter into his invitation to give ourselves for the life of the world around us.

As I reflect on Celtic retreats we used to hold, I am also revisiting many of the Celtic prayer books on my shelves. Reading Rodney Newman’s book, Journey with Celtic Saints, with its excellent bibliography has also tempted me to consider some new books to add to the list so it seems like an appropriate time to update my Celtic resource list. This is not a comprehensive list. It draws from a larger Celtic bibliography compiled by Celtic expert and spiritual director, Tom Cashman. A significant portion of this list is also contributed by Linda Lockwood of the Celtic Christianity and Music Facebook group.

Celtic Books

Adam, David: The Edge of Glory; Prayers in the Celtic Tradition; David Adam’s best known work provides prayer in lorica, litany, and free verse formats for personal and group usage.

The Rhythm of Life: Celtic Daily Prayer; This book offers a seven-day cycle of prayer for individual or community use. There are segments for morning, mid-day, and evening comprised of scripture and prayers of his own origination. Tom and I have used this for years as part of our prayer rhythm.

The Open Gate

Aelred of Rievaulx: Spiritual Friendship

Allen, J Romilly: The Romano – British Period And Celtic Monuments

Balzer, Tracy: Thin Places: An Evangelical Journey into Celtic Christianity

Bamford, Christopher (Translator): The Voice of the Eagle: The Heart of Celtic Christianity

Bradley, Ian: The Celtic Way; Still the best basic overview of Celtic Christianity. Often used as the text for initial classes on Celtic spirituality.

Following the Celtic Way, A New Assessment of Celtic Christianity

Celtic Christian Communities: Colonies of Heaven; This more recent book by Bradley takes us into practical application of the world view and spiritual practice of the Celtic Christian church. This is a “must read” for any student of the future, emerging church.

Bryce, Derek: Symbolism of the Celtic Cross

Carmicheal, Alexander: The Carmina Gaedelica; This is the classic primary source book of oral tradition collected between 1855 and 1910 by Alexander Carmichael largely in the outer Hebrides. Included are many prayer forms that stretch our 20th century definition of prayer in the Christian tradition. Some of the ”charms” and “spells” remind us of Psalms that call down God’s wrath against our enemies. There is also great depth and beauty in many prayers that have been rescued from oblivion by Carmichael. Most of these prayers are available online here.

Child, Jenny: Celtic Prayers and Reflections

Clunie, Grace: Sacred Living: Practical inspirations from Celtic spirituality for the Contemporary Spiritual Journey

Cole, David: 40 Days with the Celtic Saints: Devotional Readings for a Time of Preparation

Connell, John: The Man Who Gave His Horse To a Beggar: following in the footsteps of Aidan of Lindisfarne

DeGregorio, Scott (Editor): The Cambridge Companion To Bede

De Waal, Esther: Every Earthly Blessing; Rediscovering the Celtic Tradition; One of the best introductions to Celtic Spirituality containing splendid examples from Celtic poetry and other writings.

The Celtic Way of Prayer; This is one of my favorites which provides not just an introduction to the different aspects of Celtic spirituality but also a rich array of prayers.

Doherty, Jerry: A Celtic Model of Ministry: A Reawakening of Community Spirituality

Donaldson, Christopher: Martin of Tours: The Shaping of Celtic Spirituality

Earle, Mary C.: The Desert Mothers: Spiritual Practices from the Women of the Wilderness

with Sylvia Maddox: Holy Companions: Spiritual Practices from Celtic Saints

Ferguson, Ronald: Chasing the Wild Goose: The Story of the Iona Community

Fitzgerald, William J.: A Contemporary Celtic Prayer Book; Perhaps the best practical guide for community daily liturgy yet. Fitzgerald is a retired American priest who reframes the Carmina for today. An excellent 7-day cycle of prayer is the book’s core. The second half provides prayer for special needs and extraordinary occasions.

Blessings for the Fast Paced & Cyberspaced; Provides this extension of prayers for the hectic world in which we live today. For example, there are blessings for “the computer as I sit down to it,” for soccer moms, and for couples trying to conceive. He takes us through many routine life situations with an eye towards finding the sacred in all of them.

Fleeson, Mary: Life Journey: A Call to Christ Centred Living

Freeman, Mara: Mara Freeman Kindling the Celtic Spirit

Gameson, Richard (Editor): The Treasures of Durham University Library

Gildas and Giles, J.A.,: On The Ruin of Britain

Hardinge, Leslie: The Celtic Church in Britain

Hayward, Anne: A Celtic Pilgrimage A Walk from Wales to Brittany

Hunter III, George G: The Celtic Way of Evangelism

The Iona Community: Iona Abbey Worship Book; The forward of this wonderful book offers insight into the uses of these prayers, liturgies and litanies within the Iona Community and the thinking that underlies their composition and use. Suggestions are also made for use in Iona communities world-wide. These prayers offer insight into the essential theology and ethos of the Iona Community.

James, Chalwyn: An Age of Saints: Its Relevance for us today

Jones, Kathleen: Who are the Celtic Saints?

Lacey, Brian: Colum Cille And the Columban Tradition

Mackey, James: An Introduction to Celtic Christianity

Marsden, John: Sea-Road of the Saints Celtic Holy Men In the Hebrides

Mayers, Gregory: Listen to the Desert Secrets of Spiritual Maturity From the Desert Fathers and Mothers

McColman, Carl: Christian Mystic’s: 108 Seers, Saints, and Sages

McIntosh, Kenneth: Water From and Ancient Well: Celtic Spirituality For Modern Life; Using story, scripture, reflection, and prayer, this book offers readers a taste of the living water that refreshed the ancient Celts. The author invites readers to imitate the Celtic saints who were aware of God as a living presence in everybody and everything.

McNeill, John: The Celtic Churches, AD 200 – 1200

Mitton, Michael: Restoring the Woven Cord

Newell, J Philip: Listening for the Heartbeat of God: A Celtic Spirituality; Discusses how different persons from the Celtic tradition serve the common theme of carefully listening to God.

Christ of the Celts: The Healing of Creation; Newell connects the Celtic tradition with our more conventional Christian beliefs and offers a vision of concern for healing creation and the environment. This is a must read book for all who are passionately concerned for our world.

Celtic Prayers from Iona: The Heart of Celtic Spirituality

The Book of Creation: An Introduction to Celtic Spirituality

Sacred Earth, Sacred Soul: Celtic Wisdom for Reawakening to What Our Souls Know and Healing the World

Newman, Rodney: Journeys with Celtic Christians; This easy to read introduction to Celtic spirituality invites readers to experience their personal faith journey through Celtic lenses. Readers are encouraged to consider the many ways pilgrimage shapes their personal faith. This book with its accompanying Leaders Guide is ideal for small groups and book clubs.

Northumbrian Community: Celtic Daily Prayer; In addition to providing a daily cycle with lectionary, it also includes Complines in the tradition of various Celtic Saints, meditations, and a Holy Communion service. The latter portion offers themed and situational prayers and blessings. Two series of daily readings after the tradition of Aidan and Finian comprise the final section. This is a substantial resource.

O’Donohue, John: To Bless the Space Between Us: A Book of Blessings This is my favourite of O’Donohue’s books. A wonderful collection of prayers and blessings for many occasions.

Walking in Wonder: Eternal Wisdom for a Modern World

Anam Cara: A Book of Celtic Wisdom This is the best known of his books. AnamCara is the Gaelic word for “soul friend” a concept that O’Donohue explains in this book as well as unfolding much of his Celtic wisdom.

O’Donohue, Noel Dermont: Angels Keep Their Ancient Places: Reflections on Celtic Spirituality

Ramirez, Janina: The Private Lives of the Saints

Rees, Elizabeth: Celtic Saints Passionate Wanderers

Sharkey, John: Celtic High Crosses of Wales

Simpson, Ray: Exploring Celtic Spirituality; Founder of St. Aidan Trust, Ray Simpson offers a vision of the future as well as an exploration of our Celtic roots. Like Newell, he sees the Gospel of John as representative of the Celtic & Eastern Churches, balancing the Petrine & Pauline legs of the Christian tripod.

A Holy Island Prayer Book

Sellner, Ed: Wisdom of the Celtic Saints; This is an excellent collection of stories and legends of various saints, including some of the more obscure. Particularly useful is the introduction identifying hallmarks of the Celtic Christian worldview.

Stories of the Celtic Soul Friend; Tracking the anamchara concept of the Celtic Christians, Dr. Sellner explores the spiritual practice of the soul-friend relationship in the Celtic church. He also follows it as an overall icon of the value of relationship in the Celtic Christian culture.

Stimson, Edward W.: Renewal in Christ, As the Celtic Church led “The Way”

Taylor, Thomas: The Celtic Christianity of Cornwall

Telepneff, Father Gregory: The Egyptian Desert In the Irish Bogs

Toulson, Shirley: The Celtic Year A Celebration of Christian Saints, Sites and Festivals

Valters Painter, Christine: The Soul’s Slow Ripening In this book Christine introduces us to 12 Celtic practices. She begins each chapter with the story of a Celtic saint. A delightful and enriching book.

Earth Our Original Monastery: Cultivating Wonder and Gratitude through Intimacy with Nature

The Soul of a Pilgrim

Van de Weyer, Robert: Celtic Fire; A great whimsical collection of prayers. Good as an introduction for those that know nothing about Celtic spirituality. I love this book, which was the first gift Tom ever gave me.

Ward, Tess: The Celtic Wheel of the year: Old Celtic and Christian Prayers

Woods, Richard J.: The Spirituality of the Celtic Saints

Fiction

Beuchner, Frederick: Brendan, A Novel interweaves history and legend to re-create the life of St. Brendan the voyager whose story is related here by his long-time friend and travelling companion, Finn.

Trantor, Nigel: Columba; This is the story of St. Columba. Born an Irish prince he left his beloved country after a dispute that resulted in war, to found and become abbot of the Celtic monastery on Iona.

Tremayne, Peter: Absolution by Murder; This first book in a set of murder mysteries by the author takes place at the synod of Whitby in 664. Sister Fidelma of the Celtic Church (Irish and an advocate for the Brehon Court) and Brother Eadulf of the Roman church (from east Anglia and of a family of hereditary magistrates) set out to find the killer. Helpful in understanding some of the conflicts between the Celtic and Roman churches.

Celtic Music

Jeff Johnson at arkmusic.com is my favourite Celtic musician. For contemplative music, I particularly love his Selah Services.

The Iona Worship Group has produced several CDs of beautiful worship songs.

Eden’s Bridge, Celtic Psalms. I particularly enjoy their version of The Lord is My Light.

Online Resources

My favourite writer of Celtic prayers is John Birch at Faith and Worship.

For great prayers and commentary on Celtic Christianity, I recommend two Facebook groups: Celtic Christian Spirituality and Celtic Christianity and Music.

Another great Facebook group for some wonderful photos, prayers and links, check out The Celtic Christian Tradition.

Rev Brenda Warren has an excellent resource Celts to the Creche, that she put together several years ago for Advent. I highly recommend walking through the season (or any other season) with her help.

The Celtic Center offers an extensive resource list including books and other resources that are worth taking a look at.

I have also posted a number of Celtic liturgies and blessings on Godspace. You might like to check out some of these too:

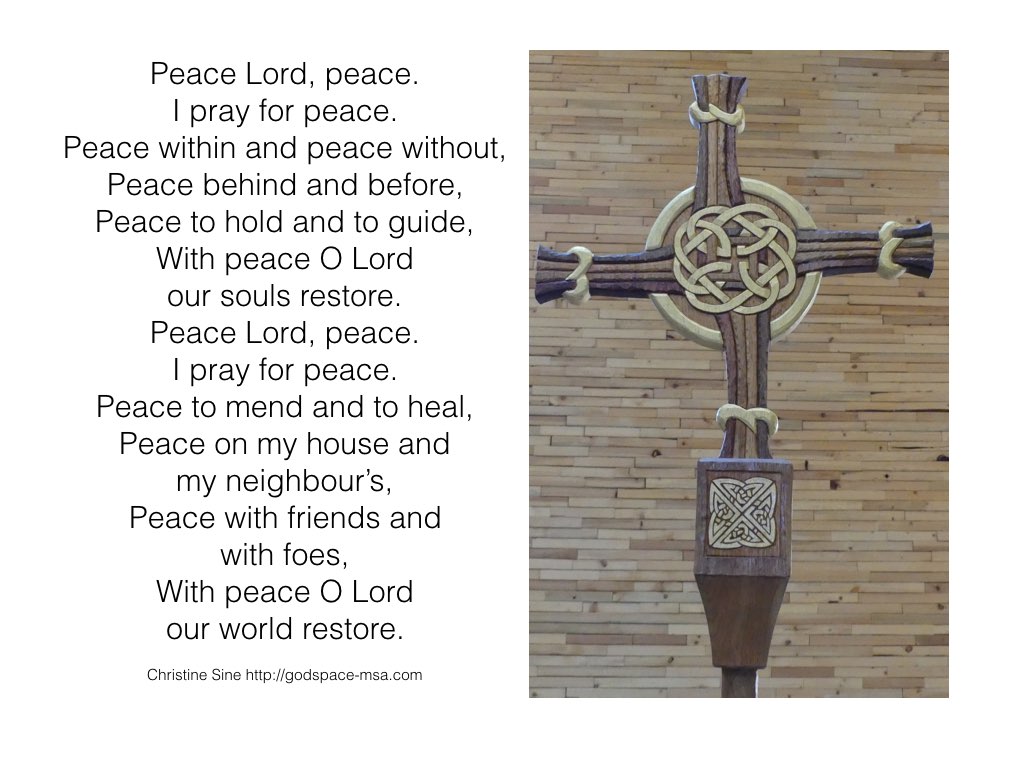

Today I am struggling with a heavy heart. The bombings today in Saudi Arabia, yesterday in Baghdad, and recently in Istanbul, and Pakistan, as well as the killings in Florida weigh heavily on my mind. My soul is weeping, my heart is bleeding. God keeps prompting me to pray for peace. Will you join me in praying for peace and a cessation of violence in our world?

July’s Featured Author: Rodney Newman

With our 25th Annual Celtic Prayer Retreat, “Celebrating the Goodness of God with All the Saints”, fast approaching, it’s fitting that we feature Rodney in our month-long focus, “Listening to the Celtic Saints” over on our Godspace Community Blog.

With our 25th Annual Celtic Prayer Retreat, “Celebrating the Goodness of God with All the Saints”, fast approaching, it’s fitting that we feature Rodney in our month-long focus, “Listening to the Celtic Saints” over on our Godspace Community Blog.

Featured Author Rodney Newman is a United Methodist pastor and higher education chaplain. He teaches undergraduate courses in Celtic Christianity and leads study abroad trips to Ireland.

In 2015, Abingdon Press published Rodney’s book, Journeys with Celtic Christians, along with a leader’s guide for use with small groups.

Rodney and his wife, Ann, live in Oklahoma City. They along with their son, a university student, and daughter in high school, are active in working for social justice and building interfaith relationships.

Celtic Prayer Retreat Early Bird Special Ends July 15th!

The super early bird special has flown the coup and the early bird special will soon fly away too! Don’t miss these special discounts.

The super early bird special has flown the coup and the early bird special will soon fly away too! Don’t miss these special discounts.

This is our 25th year joining with you at our annual Celtic Prayer Retreat. We’re excited to welcome back musician Jeff Johnson, who will lead our worship on Saturday.

To help celebrate, we’ve added a Friday evening program, Introduction to Celtic Spirituality with Pat Loughery, followed by a music jam, as well as three Saturday afternoon workshop options. We also are updating our prayer trails and will have a full morning of worship before departing on Sunday.

Find out more HERE, or go directly to tickets.

Wild Goose Festival – July 7-10

Tom Sine has invited Jensen Roll to share how he and other young changemakers are creating new forms of social enterprise to create more just communities. Tom will invite you to imagine new ways that you, your friends and community can participate in this new changemaking celebration.

Tom Sine has invited Jensen Roll to share how he and other young changemakers are creating new forms of social enterprise to create more just communities. Tom will invite you to imagine new ways that you, your friends and community can participate in this new changemaking celebration.

Look for Christine Sine at her worshop, “Messing with Spiritual Traditions.”

And come find Andy Wade over in the publishers village where we’ll have MSA resources available.

Join the Expanding Community on Our Godspace Community Blog!

We’re always looking to diversify and expand our band of poets, artists, and writers. This is a great time to join with us as the seasons change and we continue exploring the spiritual discipline of listening. We’re almost to 50 contributors from around the globe. All we’re missing is you!

Share your voice and let the world hear your unique perspective. We take blog submissions (600-800 words with a picture), poetry, prayers, liturgies, and artwork. We want this to be your place to explore the intersection of faith, imagination, and sustainability.

Drop us an email and let us know you’d like to find out more.

So Christ has truly set us free. Now make sure that you stay free, and don’t get tied up again in slavery to the law.

For you have been called to live in freedom, my brothers and sisters. But don’t use your freedom to satisfy your sinful nature. Instead, use your freedom to serve one another in love. For the whole law can be summed up in this one command: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” But if you are always biting and devouring one another, watch out! Beware of destroying one another. Galatians 5:1, 13-15 NLT

What does it mean to be free? Today is Independence Day in the U.S. when Americans celebrate their “freedom”. To be honest, it is a celebration I struggle with because I don’t believe God calls us to be independent but rather interdependent. I also realize that our cultural perspectives shape our views of freedom.

To Americans, the concept of freedom focuses on the freedom of individual choice, which can be as trivial as the right to choose whether I want my eggs sunny side up or over easy, or as serious as the right to bear arms. What I struggle with is that there seems to be little recognition of the often dire consequences our individual choices can have for the society or for the world in which we live.

To Australians, freedom revolves around the freedom of society and the recognition that our decisions all have consequences, not just for us as individuals, but for all of our society and our world. Consequently, most Australians are willing to give up the right to bear arms for the good of a safe society in which we don’t have to worry about mass gun violence and killings. In the Australian political system, voting is compulsory because of the belief that with the freedom of citizenship comes the responsibility of participation in the process that provides our freedom.

Unfortunately, neither country does very well when it comes to granting freedom to all. We like to be exclusive – no freedom to immigrants, to those of other sexual orientation, those with disabilities, those of other races or religions. Whether we think of freedom as individual or societal, we all like to limit who we give freedom to.

All of this leads me to my most important question about freedom, “What does freedom look like in the kingdom of God?”. Obviously there is an element of individual freedom – all of us need to take on the individual responsibility to kneel at the foot of the Cross, repent and reach out for the salvation of Christ. However, our entry into the family of God faces us with serious consequences for how we act in society.

Our freedom as Christians means that we no longer focus on our own needs but rather “consider the needs of others as more important than our own” (Philippians 2). It means that we live by the law of love – what James calls “the royal law” (James 2:8). In the quote above, Paul sums this up very well, “Do not use your freedom to indulge the sinful nature; rather serve one another humbly in love. For the entire law is fulfilled in keeping this one command: Love your neighbour as yourself.”

What is Your Response?

What comes to mind when you think about freedom? Take out your journal and piece of paper and divide it into 2 columns. On one side write the words that come to mind when you think of freedom. In the other column, write down the negative consequences of your personal freedoms for others, for the earth and even for your life. Listen to the video below and reflect on the true meaning of freedom.

Sit quietly for a few minutes reflecting on your lists and the video you have listened to. Allow God to speak to you. Are there changes you need to make to your original lists based on your reflections? Are there places in which God calls you to repent of your “independence”? Are there ways in which God may ask you to give up your personal freedoms for the common good?

In my vocation of prayer as a Christian mystic listening is fundamental, as is the deep silence that feeds it, moving in waves of molten magic underneath this seemingly ordinary world. But one of the first things we learn on our spiritual journey, particularly if we are called to any kind of contemplation, is that nothing is ordinary. We might experience the same things day in and day out, but within them there is still glory to be seen and wondered at. If we really had the eyes to see and ears to hear that are offered us in God’s kingdom, we could sit, entranced by our linen baskets and our gateposts, lost in awe at their symmetry, the holding together of their molecules, and any number of other factors. One leaf could hold our attention for a decade, if we could really see it.

But we are not built with that kind of patience and sight, or we have forgotten it, and it comes oh so slowly, and holy listening is the same. It also is something that travels up into our beings through our hearts and souls before it reaches our heads. This is one of the reasons that it is tough to put spiritual things into words. As a former language student I find it can feel a lot like trying to translate something from one language to another. When I want to convey what I have heard in my prayer times, the words can often come grudgingly, struggling to climb out of heart and into worded metaphor (or indeed simile!) like a mayfly wriggling out of its old skin.

At other times, the words come so fast that I can hardly keep up with them, again not exactly bypassing my head, but using far less of it than my own convoluted thinking does. Other things need to take their time, nestling into my heart or in my subconscious till they are ready to sprout into words, poetry or art. For me, creativity is the next stage on after listening and seeing, which are both ways of receiving from the Lord. Most listening prayer is of course silent, and spent in stillness, where we join with love. Then when there are things to be received, not everything is meant for sharing, as much is for our own personal edification or direction. But when there is something that could be helpful to others, I feel the urge to craft it into something shareable.

More often than not for me that means words, and it means hearing with my heart and then coating the bones of meaning with the flesh and sinews of the semantics that will enable it to be heard by others. It is perhaps somewhere in that process a lot like that larva that lay deep in the muddy layers for three years, similar to the things written in my prayer journals and languishing on my hard drive, which then finds itself grown to readiness, climbing up a stalk and working its way into a new winged life, where others can see it soar as an iridescent mayfly, even if only for a day.

As an Amazon Associate, I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links.

Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

When referencing or quoting Godspace Light, please be sure to include the Author (Christine Sine unless otherwise noted), the Title of the article or resource, the Source link where appropriate, and ©Godspacelight.com. Thank you!