Regardless of the destination, Celtic pilgrims saw their physical travels as representing an inner journey as well. They sought to avoid distractions that kept them from focusing on the presence of God. They were searching for their “place of resurrection”, a location conducive to spiritual renewal where they would invest their lives and where their mortal bodies would rest until being reunited with their Lord on the last day. (Journeys With Celtic Christians 27)

WALKING HOME

We are all walking home.

Such a long walk.

In the light, and in the dark.

Sometimes hand in hand,

and sometimes alone.

Sometimes, we stride forward

steady on the path.

Other times we trip on the stones,

on the verge.

In the day we can clearly see our way.

His smile, our light.

We know His hand of blessing,

and His gentle guidance.

While at night we feel our way,

and struggle with what we thought we knew

so well;

what had seemed clear to us in the light of day.

We encounter ourselves.

We are all walking home.

And light and shade define our days;

just as sun and moon distinguish

day from night.

If there were no questions or regrets;

struggles, slips

or back-tracks,

then we would have arrived.

We have not arrived.

Yet we may look, and find,

the blessing in the night.

Those things we cannot see in the daytime,

have a way of surfacing in the dark.

And without our eyes to see,

we feel instead, their edge.

And realise again, our deep need for Him,

who, although we cannot see Him near,

keeps vigil by our side.

Ana Lisa de Jong

Living Tree Poetry

July 2016

“But the people of God will sing a song of solemn joy, like songs in the night, his people will have gladness of heart, as when a flutist leads a pilgrim band to Jerusalem to the Mountain of the Lord, the Rock of Israel…”

Isaiah 30:29

“Behind me, dips Eternity

Before me, Immortality

Myself, the term between”

Emily Dickinson

By Andy Wade –

“God saw all that he had made, and it was very good.” Genesis 1:31

If you see my posts on Facebook, then you know that I’m a fan of mushrooms. I’m fascinated with their diversity and delicate beauty, not to mention their taste (the edible ones, that is).

You may also have seen my earlier posts exploring the amazing role mushrooms play in keeping our world healthy. Today I ran across another talk from mycologist Paul Stamets, this one from the Bioneers Annual Conference in October, 2014.

What has once again captured my imagination is how God invites us into what has already been created, discovering and finding applications for this “very good” design.

As Stamets points out, often our human-inspired solutions to so many of the issues we face create more problems than they solve, frequently making worse the very problems we were attempting to address. We’ve seen this played out in the farming industry, first with mass tilling of the soil, then the application of copious amounts of chemical fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides, and now with the advent of GMOs.

What Stamets may not recognize is that his work (and I have no clue about his religious inclinations) is actually a theological exegesis of creation, God’s very good creation. He is a prophet, of sorts, calling us to re-examine, or perhaps examine for the first time, the micro-workings and inter-relationships of all that God has formed.

Here at Godspace // Mustard Seed Associates we talk a lot about imagination and innovation. These are essential aspects of our faith as we are created in the image of God: Creator, Redeemer, Sustainer. It makes perfect sense that God’s creation would reflect these qualities, qualities we ignore to our own — and creation’s — peril.

As you watch this video I encourage you to reflect not just on the information you’re hearing, but on how this approach to discovering solutions by observing what God has already created can move us into truly uncharted waters.

“In this 6th Age of Extinctions, the biosphere’s life-support systems that have allowed humans to ascend are collapsing. Visionary mycological researcher/inventor Paul Stamets illuminates how fungi, particularly mushrooms, offer uniquely powerful, practical solutions we can implement now to boost the biosphere’s immune system and equip us with benign breakthrough mycotechnologies to accelerate the transition to a restored world.”

Tom and Andy and I have just returned from the Wild Goose Festival, a wonderful celebration that takes its name from the Celtic symbol for the Holy Spirit. We have experienced rich days of fun, food and fellowship with friends old and new while at the same time drinking in the challenging messages calling us to justice, and engagement in our hurting world.

This gathering of friends old and new made me aware once more that I am a guest in God’s world, walking, living and eating in the company of friends. Now as I sit and get the morning program ready for our 25th Annual Celtic retreat I am even more aware of this.

In some ways all of us are guests, guests of God and of God’s world, generously and lavishly experiencing the hospitality of a world that is itself a gift from God. I am aware of that as I pick raspberries in the early morning, enjoying the abundance of God’s provision. I am aware of it too as I gaze on the beauty around me and breathe in the fragrance of God’s presence.

Celtic saints, who saw themselves as hospites mundi, or guests of the world, living lightly on this earth and not becoming attached to possessions or to one location. These followers of Christ, saw all of life as a pilgrimage, a journey towards God. They believed that we live in perpetual exile, constantly seeking after Christ, and our outward journeys are to reflect our inner transformation. In exiling themselves from the comforts of home, pilgrims taught themselves to rely only on God.

The Celts had a saying for those setting out on pilgrimage: “Let your feet follow your heart until you find your place of resurrection.” This was a spot where God’s will for a pilgrim would be revealed and fulfilled. The place of resurrection need not be a famous holy site or a place far away. It could be a simple stone hut, a windswept island, or a secluded valley. The important thing was that each person needed to find their own site.

Recognizing ourselves as guests and pilgrims effects how we view everything that happens to us. Pilgrims and those who travel frequently do not take anything for granted. They learn to be grateful for comforts that those who never leave home take for granted. For a guest, each meal, especially a home cooked meal, is a gift of love from the host. Each bed provided for us to sleep in is a generous act of sharing and caring. Everything is now a gift of God.

So as you go out into the world think of yourself today as a guest of the world and prepare yourself for the amazing gifts God wants to lavish on you today – gifts of friendship, and food. Gifts of fellowship and love and caring. And let me know what new things open up for you as a result.

And don’t forget there is still time to take advantage of the Early Bird special rate for our Celtic retreat.

When I first became acquainted with Celtic Christianity, I delighted in the stories of St. Brigid. In my imagination, I could see a little rambunctious girl cleaning out the kitchen cupboard to feed a passing beggar or giving away her father’s prized sword to a leper who happened by. I saw her as an adult rushing to the aid of an unfortunate man who accidently killed the king’s trained fox and the cunning way she maneuvered his release.

It was obvious that these legends as well as those of turning water into beer and feeding the hungry were meant to show her as continuing the ministry of Jesus. She followed his example of practicing an extravagant, even reckless, generosity in caring for those most in need. This outreach to the poor, exploited and marginalized was so pronounced that Edward Sellner notes that no fewer than 23 of the 32 chapters in Cogitosus’s hagiography show her engaged with those on the extremes of society.

We often think of hospitality as ensuring that guests in our homes are well fed and made to feel at home. Different regions of the country and the world pride themselves on their particular customs of going out of their way to provide a sense of welcome to visitors. Indeed, in ancient Celtic society as in most tribal cultures, hospitality to strangers was central to their identity, a non-negotiable expectation. In the monasteries, the guest house was often the most comfortable structure in a most accommodating location.

But the Celtic Christians make sure we know that hospitality goes well beyond providing tea and sandwiches. It involves welcoming those we may not choose to be our guests, serving people who might even appear threatening, doing the hard work of challenging systems that deprive people of basic food, shelter and security.

Current events have brought these issues uncomfortably close. Unspeakable violence has turned thousands of desperate people into refugees, literally running for their lives, doing what any of us would do, looking for a place to settle and provide for their families. Immigrants are scapegoated as the source of problems that existed long before they arrived. The poor, many working multiple jobs with little social support, become labeled as “takers” and “lazy.” Citizens of ethnic origin or who practice particular religions are told to “go home,” kicked out of their own house when they already are home.

In times of economic instability and great social change, it’s tempting to give in to fear of the other, to look for someone to blame. It’s also natural to draw one’s resources close, to become selfish, and to long for a return to a supposed golden age where all was well, at least in our selective memory.

But we are not the first people to live in uncertain times. In fact, the ancient world was an incredibly dangerous place where people were very susceptible to drought, political upheaval, exploitation by the rich and powerful, and a simple infection could lead to the loss of a limb or one’s life. Yet the call of the great spiritual teachers was not to take care only of one’s own. They knew that the way to abundant life for an individual or a community was in the practice of radical hospitality – to go beyond the fear and anxiety and peer pressure – to discover that in sharing there is enough for all.

This expansive view usually attracts more excuses than proponents. Jesus was once challenged on this by a religious scholar who wanted to define “neighbor” so narrowly that it didn’t apply to anyone. In response Jesus told the story of a man who is accosted on the road from Jerusalem to Jericho and left for dead. A priest and a Levite come upon the scene but choose to pass by on the other side. It is a Samaritan, considered by Jesus’s audience as the enemy, the other, who stops and cares for the person, going out of his way to bind his wounds and arrange for his long-term recovery.

In a sermon, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. speculated on why the first two persons refused to show basic hospitality to one obviously in need. “It’s possible that those men were afraid,” he said. “You see, the Jericho road is a dangerous road. . . . And so the first question that the priest [and] the Levite asked was, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” But then the Good Samaritan came by. And he reversed the question: “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?” That’s the question before you tonight.”

So how do we answer that question? Do we focus more on our own concerns to the point that it debilitates us from acting on behalf of others? Do we make excuses – we don’t have the right skills or the proper resources? Or dare we risk following the Samaritan into a love that asks no questions about ethnic or religious identity, about background or worthiness, and to be willing to be taught by our enemies what love of neighbor means?

There is a story of a poor man who asked St. Brigid for a small amount of honey. She expressed her sorrow that she had none to give but then she heard a hum of bees coming from beneath the floor of the house. When they dug into the place of the noise, they found enough honey to give to the man who received the gift with thanks and went on his way rejoicing.

While this story may not be as dramatic as others we know of the saint, I find it fascinating in how she was present for the man. She didn’t question why he was poor, or want to know what he was going to do with the honey, or why he didn’t ask for something more substantial to eat. No, she simply offered him the hospitality of truly listening to him. And in that act of listening she heard the humming of the answer to his need. Sometimes showing hospitality involves the hard work of advocacy, establishing shelters, and investing time and money. And sometimes it is shown in the simple act of listening and in so doing we may just discover that what is needed has been with us all along.

The great Irish teacher John Scotus Eriugena taught that God speaks to us through two books. One is the little book, he says, the book of scripture, physically little. The other is the big book, the book of creation, vast as the universe….

Eriugena invites us to listen to the two books in stereo, to listen to the strains of the human heart in scripture and to discern within them the sound of God and to listen to the murmurings and thunders of creation and to know within them the music of God’s Being. To listen to the one without the other is to only half listen. To listen to scripture without creation is to lose the cosmic vastness of the song. To listen to creation without scripture is to lose the personal intimacy of the voice… In the Celtic world, both texts are read in the company of Christ.

J Philip Newell in Christ of the Celts

There is within Celtic Christianity a deep appreciation of the natural world that grew out of the belief that all creation was birthed not out of a void of nothingness but out of the substance of God. Creation is translucent, the glory of God shines through it.

What is your response?

What difference would it make if we viewed everything as a translucent curtain through which the glory of God shines? Grab your journal or a sheet of blank paper, a coloured crayon or pencil and a pen and head out into your closest green space. Look around. What immediately catches your attention? Perhaps it is a rock of a certain shape, or a leaf of a special colour. It might even be a weed that you want to pull out! In what ways does the glory of God shine through it? Take a few moments to pay attention to the object and reflect on it in your journal.

This view of the earth is so important. How we view God’s creation reflects our attitude towards it. If we believe this world is just a place to build our houses, drive our cars and dig for oil we will have a very utilitarian attitude towards it, with little respect or concern for its preservation. If we believe that it was created from the substance of God and reflects the glory of God, we see it as sacred, a beautiful tribute to the God who created it and loves it. It is to be reverenced (not worshipped) cared for and protected.

It is not only the Celts who were aware of the beauty of God shining through creation. The Hebrews too were aware of this as is expressed in the following responsive prayer from Psalm 65. This prayer is part of this longer litany for creation.

God you call forth songs of joy from all the earth

You answer us with awesome deeds of righteousness,

God our Saviour you are the hope of all the ends of the earth

You are the hope of the farthest seas,

When morning dawns and evening fades

You call forth songs of joy

God you call forth songs of joy from all the earth

You care for the land and water it;

You enrich it abundantly.

The streams of God are filled with water

To provide the people with grain,

For so you have ordained it.

God you call forth songs of joy from all the earth

You drench its furrows and level its ridges;

You soften it with showers and bless its crops.

You crown the year with your bounty,

And your carts overflow with abundance.

God you call forth songs of joy from all the earth

The grasslands of the deserts overflow;

The hills are clothed with gladness.

The meadows are covered with flocks

And the valleys are mantled with grain;

They shout for joy and sing

God you call forth songs of joy from all the earth

What is your response?

Pick up a leaf. Place it behind the next clean sheet of paper in your journal and make a rubbing of the leaf with your coloured pencil. Be gentle but press hard enough that you begin to see the outline of your leaf’s shape and its stem and veins. Take time to study your leaf closely. Smell it, rub your fingers across its surface. Touch it to your skin.

Next to your rubbing reflect on the following thoughts: What does this leaf tell you about the God who created it? What does it tell you about yourself as a created being? Your thoughts may have come together into a prayer or poem. Write that down too.

Now read through the prayer above several times. What other thoughts come to mind? Are there ways that God is prompting you to show your respect for creation in new ways?

by Nurya Love Parish

Twenty years ago I was a young woman in my early twenties. I was just beginning ministry. I knew enough to know that our world was broken by sin and violence. I also knew I wasn’t well enough equipped to resist the sin and violence in my own soul. And I was in a bookstore.

Those were the days before the Internet and before Amazon: before anyone could publish writing to the world on their own from their home, before bookstores mostly vanished from Michigan, where I live. In those days, when I needed more wisdom than I could find on my own, those days before Google and Facebook, when email was still a novelty and the Book of Common Prayer was not yet my own, I went to a bookstore.

On this day, on the shelf of a bookstore whose name I no longer recall, I found The Cloister Walk by Kathleen Norris. That book came home with me. Through it I met a man whose influence on my life and ministry has been second only to the influence of Jesus Christ. I met St. Benedict.

I am glad I met him that way. The other way to meet St. Benedict is by reading his rule itself, which has always been too dense and different from my own life for me to fully grasp, though I keep trying. Kathleen Norris’s book told the story of her time with the community of St. John’s Abbey, in Collegeville, Minnesota. Her reflections made St. Benedict approachable, even friendly. Norris described a community marked by worship, humility, and honesty. They were that way for a reason: the Rule they followed.

As soon as I met St. Benedict through reading about Kathleen’s experiences as a Benedictine oblate (a lay affiliate of a monastery), I wanted this experience myself. At the first opportunity, I made a retreat at a Benedictine house, where the world Kathleen described came to life. My first Benedictine retreat was at Mount Saviour, a Roman Catholic monastery in New York State. I was probably the only twenty-six year old single female Unitarian Universalist pastor that visited them that year. But they couldn’t have been more welcoming.

St. Benedict laid a foundation for communities to institutionalize kindness. “All guests are to be received as Christ,” the rule states. He also created a rhythm of life that still is kept by communities around the world: each day contains prayer, work, study, and rest.

H e serves an antidote for the restlessness of our world: his vow of stability, a commitment to a certain place and people for a lifetime, gives incentive to work things through together for the common good, rather than leave when the going gets rough.

As the daughter of a refugee, I know that geographic stability can be an impossible, longed-for luxury. And yet, as someone whose ministry has taken place for the last fifteen years in one place (albeit in two denominations), it is Benedict’s commitment to stability that has come to mean the most to me. Sin and violence have not lost their grip on the world. But as I practice faith in my particular place, I come to understand more and more clearly what is wrong in the particular slice of the world I live in. I also discover more and more about how God is at work in my place. Fifteen years in, I have relationships that would have been impossible fifteen years ago. Some of those relationships have shown me more about the sin and violence in my own soul. Many have helped me overcome it.

In Benedict’s commitment to creating a school for God’s service through stability, conversion of life, and obedience, I found a path for discipleship that guides me still. It is not for everyone. But it is for me.

The Cloister Walk is still in print, twenty years later. In its day, it was a New York Times bestseller. More people than I are looking for a way to serve God in this world. Listening to St. Benedict – and listening to the many people who have followed his Rule through the generations – will help us find one.

The Rev. Nurya Love Parish is a priest with the Episcopal Church and ministry developer for Plainsong Farm, a community supported farm attempting to explore agriculturally supported discipleship outside of Grand Rapids, Michigan. She curates the Guide to the Christian food movement and edits Grow Christians, a group blog for families practicing faith at home.

The Rev. Nurya Love Parish is a priest with the Episcopal Church and ministry developer for Plainsong Farm, a community supported farm attempting to explore agriculturally supported discipleship outside of Grand Rapids, Michigan. She curates the Guide to the Christian food movement and edits Grow Christians, a group blog for families practicing faith at home.

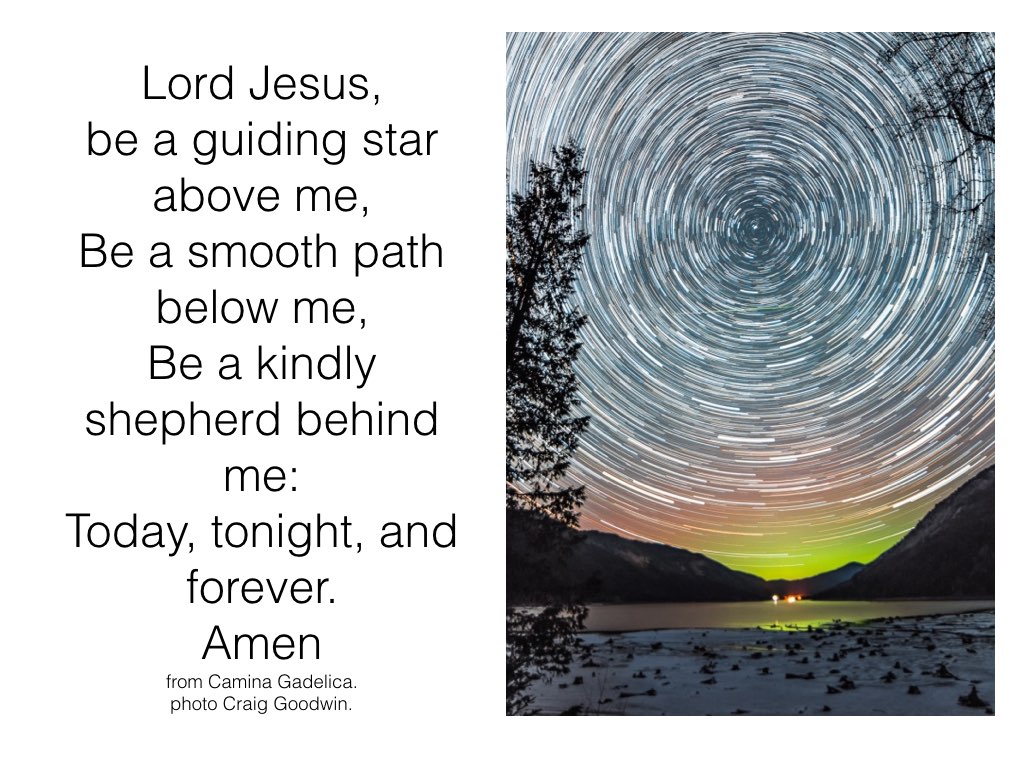

Psalm 19 tells us that the heavens speak to us:

The heavens are telling the glory of God;

and the firmament[a] proclaims his handiwork.

Day to day pours forth speech,

and night to night declares knowledge.

There is no speech, nor are there words;

their voice is not heard;

yet their voice[b] goes out through all the earth,

and their words to the end of the world.(verses 1-4, NRSV)

What are the heavens saying to us? Are we listening?

We are good at acknowledging God as our redeemer, the righteous one who communicates to us through the Bible and calls us into relationship through his son, Jesus. Yet we have neglected to see God’s handiwork in nature as a call to prayer and praise. We have missed something central about how God communicates to us through the Creation.

We are good at acknowledging God as our redeemer, the righteous one who communicates to us through the Bible and calls us into relationship through his son, Jesus. Yet we have neglected to see God’s handiwork in nature as a call to prayer and praise. We have missed something central about how God communicates to us through the Creation.

Maybe this omission comes from our fear that we will be viewed as pantheists if we talk about God’s hand in creation. Maybe the pervasive emphasis of New Age thinking has made us fearful that we will lose a Biblical perspective if we think too highly of creation.

The New Testament doesn’t talk about God the Creator as much as the Psalms do, and maybe we are concerned that we need to faithfully reflect the priorities of the New Testament. Maybe we like viewing ourselves as autonomous human beings who don’t need to depend on God for every breath and every meal. I don’t know for sure what has caused the focus on God the Redeemer while neglecting God the Creator, but I do know that we are missing something wonderful.

The Celtic saints would agree. The Celts saw God’s handiwork clearly in nature. They expected God’s creation to communicate about the One who made it. To them, a shamrock spoke of the Three-in-One God, and the stars and sun spoke of God as light. They heard the “voice” of the Creation praising God all the time, and they joined in.

They understood that the supernatural realm is very close to the physical world; in fact they believed and experienced the spiritual world touching our world in certain places. They had a name for the places and times when the spiritual world was most near: “thin places.” Water, oak forests and mountains were considered to be “thin places,” as were saints’ birthplaces and sites of past miracles and extraordinary events.

The significance of “thin places” drew the Celtic Christians into frequent pilgrimages. Celts valued travelling for a spiritual purpose, to visit a place or places where God might be close by. In addition, the profound connection that the Celts felt between their lives and God’s creation spilled over into their art. It’s no accident that there are rabbits, mice, lizards and fish drawn between the lines and around the edges of the pages of the Book of Kells, a beautiful illuminated manuscript of the four Gospels.

Sister John Miriam Jones, in her book With an Eagle’s Eye, writes that their sense of God’s presence and love experienced through the creation led the Celts

“to artistic expressions using metal, wood, stone, paint, words, and music. These wholehearted art lovers found countless ways to utilize the arts in expressing their beliefs and their love. The monastic era coincides with the production of the best of Celtic metalwork, manuscripts and sculpture – all of which attest to their awareness of and yearning for God’s immanent presence.” [1]

She believes that all of this creativity and artistry come from the truth that “deeply felt love requires expression.” [2]

The Celts saw in the creation the deep love of the Creator, and they felt moved to create also. Their art was deeply symbolic. The Celtic knots that have become so popular in jewelry and art and symbolic of the love of God, which has no beginning or end.

Celtic Christians listened to the “voice” of Creation, and that voice called them to honor God by expecting to find God everywhere, especially in thin places. The “voice” of creation called them to create beautiful art that manifested their love for God. We have so much to learn from them.

[1] Sister John Miriam Jones, S.C., With an Eagle’s Eye: A Seven Day Sojourn in Celtic Spirituality (Notre Dame, Ind.: Ave Maria Press, 1998), 65.

[2] Ibid.

As an Amazon Associate, I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links.

Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

When referencing or quoting Godspace Light, please be sure to include the Author (Christine Sine unless otherwise noted), the Title of the article or resource, the Source link where appropriate, and ©Godspacelight.com. Thank you!