This is yet another gem from Christine Valters Painter in which she invites us to journey with 12 monks and mystics into a deeper understanding of life, faith and personal growth. From the prophet Miriam, to Thomas Merton Christine spans the centuries of wisdom offered by such diverse characters as King David, the Celtic saints Brendan and Brigit, and St Francis of Assisi. I love the way she explores the archetypal characteristics of each and the embodiment of these characteristics in our own lives.

This is not a book to be read quickly. Christine comments: The expressive arts enlarge our capacity to see the holy at work in the world. (xix). Like all her books, Illuminating the Way is rich with invitations to creative practices, guided meditations and the recitation of beautiful prayers and poems that prove this is to be true. This entry into the holy presence of God is further enriched by the inclusion of images of each monk or mystic by Marcy Hall that we are encouraged to explore and reflect on and by scripturally based meditations by her husband John.

I thoroughly enjoyed taking time to reflect on the images and engage in the creative practices, as well as read the stories. It is a book that I heartily recommend to you. Study it alone or with your small group. I am sure you will also find it to be an enriching experience.

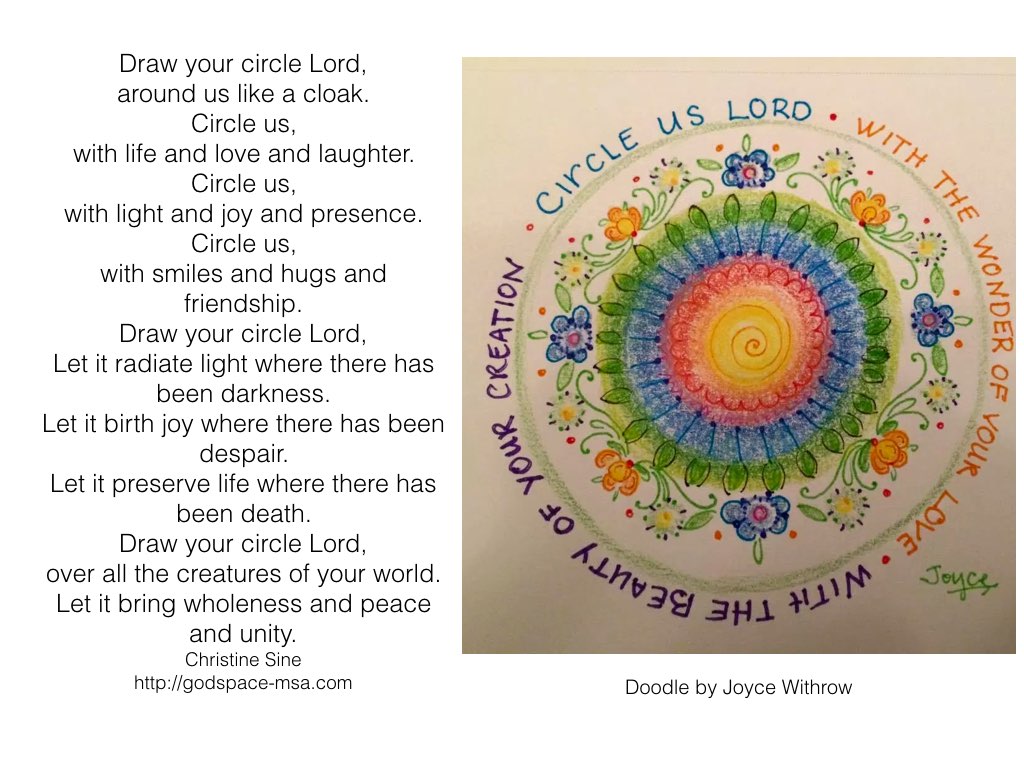

Last week some of you may remember I posted this circling prayer meditation. One person commented: In a busy place draw a circle around you with your finger and envision God enfolding you in a cloak, ask God for peace to hear him. I have spent the whole week doing just that – not just for busy places but also for stressful and challenging places.

And there have been many stressful places this week. I am entering my last week as Executive Director of Mustard Seed Associates and though the transition to Andy Wade’s leadership could not have gone more smoothly, it is still stressful… for both of us, as we try to juggle all the details that such a transition encompasses. Fortunately, as Andy keeps reminding me, I am not going far and will continue to advise and contribute to Godspace.

From Imaginary to Real

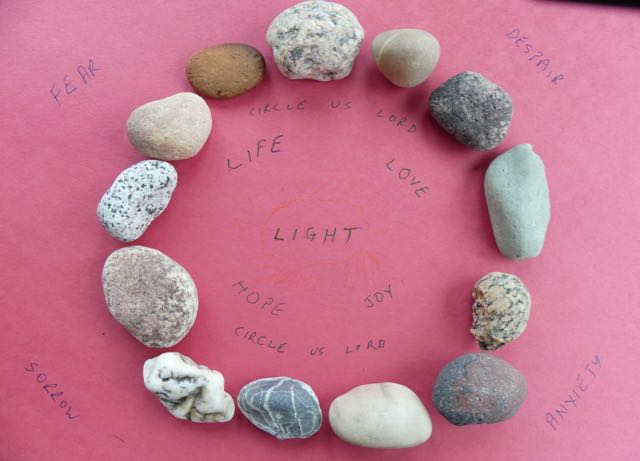

I used this process for my reflection (updated in 2017) but even more helpful for me has been an exercise to move my circles from the imaginary to the real. I didn’t use a cloak, but instead grabbed a piece of construction paper and some of my rock collection and made a circle.

I sat for several minutes contemplating my circle and reminding myself of all the attributes of God I wanted that circle to embrace. I wrote those around the inside, added the words circle us Lord, and envisioned that enfolding cloak of God around me. Then, outside the circle, I wrote the attributes I would like to see excluded from God’s enfolding cloak. It was so comforting and strengthening.

As I continued to meditate on my circle, a heart shaped rock I acquired recently caught my eye and I knew it had to be added to the centre. God’s loving heart is at the centre of my circle. God’s loving heart is where life and light, hope and joy abide.

The finished “work of art” sits on my desk as a reminder of God’s embracing presence. It is a wonderful way for me to recentre my soul and my spirit each morning. It has already inspired the creation of the prayer above and I suspect will inspire other creations in the future.

What is your response?

When I posted a meditation on circling prayers in January this year, I received several responses from people who were inspired to use their own creative medium to respond – like Joyce Withrow who created the doodle above. I invite you also to respond in the way that seems most appropriate for you. What is the creative activity that most inspires you? Perhaps you like to doodle, or knit, or paint. Or you might prefer to garden, or go running or draw on a sandy beach. Or perhaps you like to sing or compose music. All of these creative exercises can be used to craft images that reflect the encircling embrace of God.

Gather your materials. Sit quietly for a few moments with your eyes closed. Listen to the video below. Repeat the words circle me Lord aloud several times. Draw an imaginary circle and picture God enfolding you in a cloak.

What images come to mind? Express those with your creative gifts.

Father James Martin in his book, My Life with the Saints describes saints as simply being “friends on the other side.” For this lifelong Protestant, this was eye-opening, mind-bending, and soul-expanding good news. Father Martin’s words allowed both mind and soul to intersect and to assimilate the idea that I could experience and embrace Celtic and Anglo-Saxon saints as friends on the other side.

While working on the Master of Divinity degree in a seminary where women are trained that they are not allowed to become pastors or teachers of males, discovering St. Hilda (Hild) of Whitby in a History of Christianity course was both life-changing and liberating. When the professor taught about the Celtic and Catholic gathering of minds concerning some theological issues at St. Hilda’s double monastery for the Synod of Whitby in 664 AD in Northeast England, I was both stunned and elated to learn that this synod was held at a double monastery under the authority of an Abbess named Hilda. Wow, that was life-altering news that a woman in history had been in spiritual and vocational leadership over both women and men.

Curiosity got the best of this former librarian and I began chasing Hilda by reading everything I could find on her and I knew that I must travel to those places where she had lived and served. Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People became my bible of sorts as I began this unexpected journey of chasing Hilda and her Celtic and Anglo-Saxon friends. Just as the Synod of Whitby held at St. Hilda’s monastery was a watershed moment in the Celtic Church, it was for me also.

My spouse who is a fellow pilgrim in life travelled with me on our first journey of chasing Hilda. We arrived in Northeast England in February and stayed in Ampleforth Abbey as we thought it was close to Whitby. While staying in this stunningly beautiful and historical English Benedictine Abbey, we excitedly told a monk at breakfast that we were headed to Whitby for the day. Almost instantaneously, we received a message from the Abbot that he would not allow us to go to Whitby as the curving, narrow icy roads were too treacherous. My husband and I still muse that this was our first encounter with the power of Abbots. Later on during the week when the snow and ice melted, we finally made our pilgrimage to Whitby where we wandered in wonderment through the mystical grounds and magnificent museum. We were really in the very place where St. Hilda had resided and had developed this coastal land into an Abbey that made a significant mark on Christian history.

Back at home, while gazing upon my first icon of St. Hilda of Whitby, I sensed that she was telling me, “get thee to Lindisfarne.” Yes, she spoke in Old English. I explained to my spouse that we should go to Lindisfarne and somehow he trusted that Celtic command. I had no clue where Lindisfarne was, but had read about it in reference to Aidan’s call to Hilda to become an Abbess. Two weeks later, we were once again chasing Hilda by plane and a little coracle of a car to Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island where the magnificent early 8th c. handwritten and illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels was produced. Yes, Hilda was correct, I did need to go to Lindisfarne as it provided the background information to better understand the Celtic and Anglo-Saxon saints.

Throughout the past fifteen years of chasing Hilda on numerous pilgrimages to Lindisfarne; Whitby; Hartlepool; Hackness; Monkwearmouth; St. Hilda’s South Shields Church; Hinderwell; and even modern day St. Hilda’s Priory in Whitby, it has been an enriching experience of discovery, faith, and transformation. Visiting and praying in ancient Celtic monastic sites and in churches etched with a millennia of prayers associated with St. Hilda have all enriched my love and admiration for this courageous and wise woman of vision and faith. Studying about Hilda’s family and especially her sister, Queen Hereswith, has also led to further journeys in East Anglia and Central France east of Paris including Chelles, Faremoutiers, and Jouarre.

In 2013, for an Advent spiritual discipline, I composed a daily devotional on the Celtic and Anglo-Saxon saints entitled, “Celts to the Creche” that became part of my Saintsbridge blog. It continues to be a delightful and humbling surprise that people from around the world are also interested in these saints and read these posts.

Chasing Hilda has gloriously grown new friendships in both the U.S. and the U.K. with those who also have a passion for St. Hilda and the Celtic and Anglo-Saxon saints. Thank you St. Hilda for being a friend on the other side and as I chased you, I think you may have been chasing me also.

*If you would like further information on St. Hilda of Whitby, please follow this link: http://saintsbridge.org/2013/12/01/st-hilda-of-whitby/

by Jan Blencowe

The imagery of a nest fascinates me. Have you ever come upon a bird’s nest in the autumn when the trees are almost bare? Have you taken a moment to observe it or even hold it in your hand? They are marvels of construction, made from the most fragile materials, grasses, twigs, fur, sometimes bits of ribbon or scraps of frayed cloth and paper. Yet, many are amazingly sturdy. Carefully and expertly woven, they are the containers for the next generation of bird, so the species can continue and life will go on.

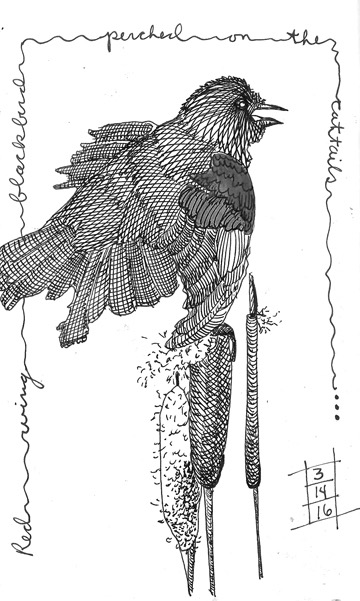

I have always dearly loved the story of the Celtic St. Kevin and the blackbird. While kneeling in prayer, deep in contemplation, arms outstretched and palms facing upwards towards heaven, waiting to receive what the Lord would bestow, a blackbird lands, and treating his hand as a nest, lays an egg there. St. Kevin with a patient and loving heart, neither closes his hand nor withdraws it, but remains still in prayer and contemplation until the egg is hatched.

Here in this tender story I find a picture of God’s care for us and a model for our care of creation. We see St. Kevin demonstrating the patient and loving heart of God towards us, extending a hand of mercy, compassion and provision that never closes and is never withdrawn. A hand that steadfastly remains open until we are fully formed and hatched. A hand that supports and shelters us like a nest until we hatch from this world into everlasting life and are transformed from an egg into the wholeness and completeness of who we are truly meant to be.

I think it is telling, that this story has a blackbird using St. Kevin’s hand as a nest and that he tirelessly remains, arms outstretched, sheltering and protecting the blackbird until the egg has hatched. In this I sense a deep message about our own roles as protectors and stewards of the natural world.

Nests while often sturdy, hold eggs which are fragile. Recently, in my wanderings among a thicket near the beach I came across the remains of a robin’s egg on the ground. It was the most impossible shade of delicate blue imaginable. These are the sorts of discoveries I like to record in my nature journals, so I sat down and made the entry with pen and paint. I wanted to inspect it more closely so I tried to pick it up but the vulnerable shell collapsed at even my lightest touch. Had St. Kevin closed his hand he easily could have crushed the egg and extinguished all possibility of life continuing.

God has placed the whole of his glorious creation within the hand of humanity and it is within our power to close our hand and destroy it. Practices like deforestation and strip mining, crush the possibility of life on a grand scale. Even the simple construction of residential developments and shopping centers are like a hand closing and crushing a place where life in the natural world could incubate, hatch and flourish. We all share this planet and certainly we human beings have needs for our own existence. Yet, after our use of the land, we withdraw our hand from nature and rarely think to spend any effort at restoration. Where we could replant, and recreate habitat around our homes, shopping malls, offices and schools we withdraw our hand and give no thought to how we could patiently and lovingly support the whole of creation that surrounds us. God is treating our hands as nests. He is trusting that we will neither close our hand and crush his creation nor withdraw our hand from supporting and protecting it.

I believe that if we remain in prayer and contemplation like St. Kevin we will see a vision of God placing the care and support of his creation in our hands. Then we will use our hands to shelter birds and wildlife, plant seeds, garden to create native plant communities and give thought to restoring the landscape after we have cleared and constructed on scales both large and small.

What fragile “egg” has God placed in your hand? What small part of the creation is within your reach? Will you close or withdraw your hand, or will you lovingly and patiently open your hand and tend the earth given into your care? By designating us stewards of the earth, God demonstrates and amazing amount of trust in us to follow St. Kevin’s example to remain gentle, open and actively involved in supporting life on the planet, as well as the planet itself. May we all seek ways to follow that example so our hands become nests where life can flourish.

Jan Blencowe earned her BFA in 1984 from Caldwell College. She has enjoyed a long career as a successful landscape painter, but her most profound joy is keeping a personal sketchbook of her life experiences. The boldness of an ink line on paper and the use of free flowing water media allow her to engage life’s moments both great and small with gratitude, and presence. Her deepest connection is with the natural world and she makes a regular practice of sketching the ongoing drama of life that unfolds at the beaver pond on her property in Clinton, Connecticut, and throughout New England’s woods and marshes. Her nature journal sketches are featured in several books on sketching outdoors and in interdisciplinary science curriculums.

Jan Blencowe earned her BFA in 1984 from Caldwell College. She has enjoyed a long career as a successful landscape painter, but her most profound joy is keeping a personal sketchbook of her life experiences. The boldness of an ink line on paper and the use of free flowing water media allow her to engage life’s moments both great and small with gratitude, and presence. Her deepest connection is with the natural world and she makes a regular practice of sketching the ongoing drama of life that unfolds at the beaver pond on her property in Clinton, Connecticut, and throughout New England’s woods and marshes. Her nature journal sketches are featured in several books on sketching outdoors and in interdisciplinary science curriculums.

Her sketching and nature journaling can be found at: Jan Blencowe Sketchbook.

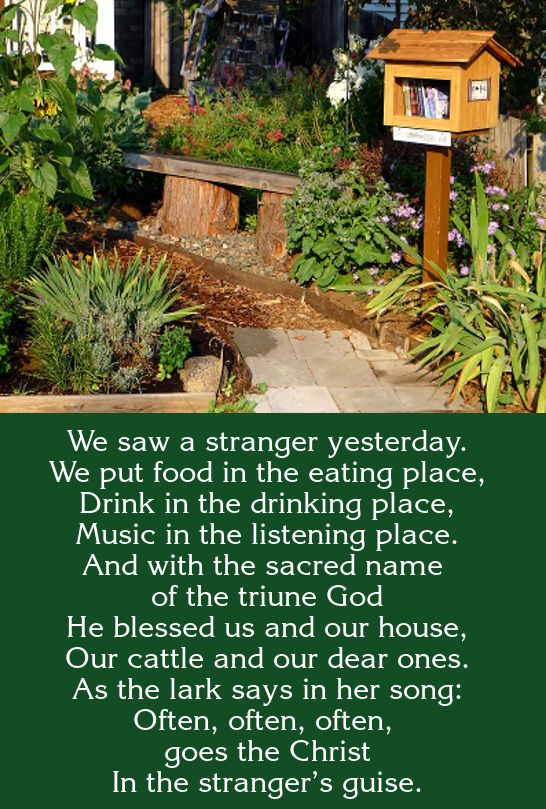

As we continue our Godspace theme of listening to the Celtic Saints, I’m struck by how important the area of hospitality is. The ancient rune to the right is a good example of the Celtic mindset when it comes to entertaining both neighbor and stranger.

As we continue our Godspace theme of listening to the Celtic Saints, I’m struck by how important the area of hospitality is. The ancient rune to the right is a good example of the Celtic mindset when it comes to entertaining both neighbor and stranger.

Many of us are “really nice people”, but so many of us, at least in the United States, have lost the art of true hospitality. We’ve become accustomed to returning home, driving into the garage, and walking into the house. When we do venture outside more often than not it’s into the backyard or back to the car to run a quick errand.

Before I launch into my top ten ideas, let me begin by confessing that some of them are still just ideas. While I’ve done many of these things, some are still forming in my mind and the ones I’ve done are still a work in progress. With that caveat, here we go:

1. Look for barriers: Does the border of your front yard create a barrier to hospitality? Is there a fence, a row of shrubbery, or other obstruction that says, “Stay on your side”? Take it down or find creative ways to poke holes of hospitality into it.

2. Put up a Little Free Library: This one’s pretty simple and one of the first things we did. You can find instructions, ideas, and plans at the LFL Website. Once you’ve got yours up and running, why not encourage an LFL community tour? You’re likely to find others in your community, and what a wonderful way to walk the neighborhood! Although we live on a small loop off the main road, our library is so well-used that I’m building a bigger one to hold all the books, adding a children’s section for all the kids who stop by with their parents!

3. Add a bench or hospitality space: A bench or space near the sidewalk is best as it doesn’t require venturing deep onto someone else’s property to take a rest.

4. Add a pet station: Dogs and other animals get tired and thirsty. Why not create a space with water, “poop bags”, and a shady spot to rest?

5. Welcome creation: Speaking of animals, don’t limit your hospitality to domesticated pets. The Celts were great at recognizing and welcoming all of God’s creation. Bees, butterflies, and other insects need water. Keep a birdbath full of fresh water, and include rocks so that there are different levels of access for the different types of animals. Also incorporate rocks and rotting wood into your garden space; good animal homes are often difficult to come by.

6. Create a “free” garden space: We added a free sun tea and herb garden and invite neighbors to feel free to cut and pick as needed. You could also consider a cutting flower garden, fruit trees, or fruit bushes.

7. Did I mention creation? Part of welcoming creation is making sure that your space is safe and accessible to animals. A birdbath too near the ground may be accessible to all, but a bit too tempting for the cat lurking nearby. Lawn and garden sprays that kill weeds and pests may make an area pretty, but they also kill bees and other beneficial wildlife.

7. Did I mention creation? Part of welcoming creation is making sure that your space is safe and accessible to animals. A birdbath too near the ground may be accessible to all, but a bit too tempting for the cat lurking nearby. Lawn and garden sprays that kill weeds and pests may make an area pretty, but they also kill bees and other beneficial wildlife.

8. Create an alternative sidewalk: While at Wild Goose Festival, I was talking with a new friend about how to create hospitality in a long, narrow section along the side of his house. As we talked I had this vision of an alternative sidewalk. One could fairly easily create a wandering path, somewhat parallel to the sidewalk, that meanders through lavender, hyssop, or other flowers and fragrances. Invite your neighbors to an alternative path that helps them slow down and enjoy the sights, sounds, and smells of creation.

9. Create a children’s garden: If you have children in your neighborhood, why not create a garden area where kids can get their hands dirty and learn the wonders of growing their own food? One friend put in a raised garden and had the kids help by decorating the wood surrounding the beds. Ask the children what their favorite vegetables are and let them help plan the garden. If you’re in an area where strawberries grow well, why not plant a section of strawberries they can munch on while tending the garden?

10. Spend time in the front yard: All of these ideas are helpful but the best way to meet your neighbors and enter into engaging conversations and new friendships is to make sure you spend time out where you can meet them.

I realize that people may be uncomfortable with some of the ideas here. Opening our front yards to neighbors is not “normal”, and some of these may be more of a stretch for you than others, so try to start with entryways to hospitality that are easy. You can always expand as you and your neighbors get comfortable with this strange new idea of front yard hospitality.

- What have you tried?

- What has worked… or not worked so well?

- If you live in an apartment or don’t have a front yard, how can you use what you have to cultivate

- neighborhood hospitality?

- What other ideas do you have?

I’ve just started birding, and it is teaching me a lot about listening. I’m in a beginner’s ornithology field class. It started in the cold, early spring when the trees were still bare here in the Northeast. That was good. The birds were in plain view, even if at a distance through binoculars and scopes. So we quickly started learning their names, colors, and markings. But now, in the early summer, the trees are fully leafed, the oak, maple, locust and basswood trees making an impenetrable green wall. Almost all we have now are the sounds. It was maddening at first, a cacophony of random calls and no easy way to know who’s who.

But I am learning to focus my hearing, more than my binoculars these days. Best now to stand in one spot and strain to hear, to listen deeply. I love being with someone whose ear is trained and can guide me into this soundscape. What sounds to me to be various squawks and cheeps, to the trained ear are each distinct vocal signatures…a chipping sparrow, a goldfinch, a chickadee. I am starting to be able to discern the everyday familiar sounds and to catch, from time to time, the unusual snippet of a song, the arrival of an unfamiliar bird and an opportunity to learn.

But I am learning to focus my hearing, more than my binoculars these days. Best now to stand in one spot and strain to hear, to listen deeply. I love being with someone whose ear is trained and can guide me into this soundscape. What sounds to me to be various squawks and cheeps, to the trained ear are each distinct vocal signatures…a chipping sparrow, a goldfinch, a chickadee. I am starting to be able to discern the everyday familiar sounds and to catch, from time to time, the unusual snippet of a song, the arrival of an unfamiliar bird and an opportunity to learn.

I’ve also learned about the spring migration, with many species flying a thousand miles or more from their tropical winter homes to be with us for the summer, and then return. This has been called the pulse of the living planet. On a single day in May, 15,000 birders from 145 countries in the online “eBird” community, counted 6,242 species and recorded their locations.

The early Celtic Christians seemed to have ears well trained for listening. Deep listening. Even extreme listening. My favorite birder is St. Kevin. His beloved place was Glendalough, with its lakes and cliffs, south of Dublin. One morning in the early 500s he lifted his hands in prayer. It is said that in the stillness and openness of his prayer, God invited a blackbird to nest there in his open palm. She even lay eggs. And Kevin, in deep contemplation and in compassion for the creatures, kept his pose for weeks until the eggs hatched, and the chicks grew and finally took flight out beyond his loving hand.

Stillness, openness, appreciation of the familiar, being ready for the unexpected — I’m learning these lessons from birding, from Kevin, and from those straining to listen more deeply to God and to each other.

Seamus Heaney, winner of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature, reads his poem, “St. Kevin and the Blackbird”

John Finn is an engineer, climate change educator, and church servant-leader. He was a contributing author to Secular Monasticism: A Journey which is the story of the Lindisfarne Community in Ithaca, New York, where he was ordained. Current projects include engineering with AguaClara sustainable water treatment, and public speaking with Citizen’s Climate Education. He lives in Ithaca with his wife and two grown children. John worships with Living Hope Fellowship and loves making maple syrup and kayaking on Cayuga Lake.

When you overhear someone talking about their friend you know that more information is needed to determine the nature of the relationship. That term could refer to people who spend a great deal of time together, or a casual acquaintance, or even strangers who belong to a mutual shared social network.

The foundation of ancient Celtic society was the tuaths, small tribal villages that provided a sense of identity built on interconnected relationships. When Christianity arrived, the Celts readily accepted the desert tradition of soul friendship, intimate relationships nurtured between two persons for the purpose of mutual growth in faith. This practice felt right, acknowledging the communal nature of the Christian life while demanding individual accountability.

“Soul friend,” or “anamcara,” was not a generic term; it had the specific meaning of an intimate bond where two people opened their hearts to one another, sharing their doubts and fears, their struggles and successes, encouraging one another on the journey. It called for active listening, speaking when necessary but always out of a knowledge of who the other person was and what they needed.

Stories abound of soul friendships from the Celtic saints. St. Brigid, for instance, required the practice. When overhearing a young man mention that his anamcara had died she insisted that he find another one immediately, “A person without a soul friend is like a body without a head,” she famously remarked.

These relationships often flourished regardless of differences in age or gender and persisted even if the participants became separated by great distances, or, as in one delightful account involving Ciarán of Clonmacnoise and Kevin of Glendalough, even death.

In 6th century Ireland, Ciarán stood out among a very illustrious crowd. While still a student at Clonard and later on Inishmore, his distinguished teachers predicted that he would accomplish great things. Indeed, while still a young man, he founded a significant monastery at Clonmacnoise situated at the intersection of major travel routes in the center of the island. Kevin was just as gifted but his calling was expressed more modestly, gaining renown as a person of great holiness and prayer. He attracted quite a following and tried to preserve his time alone by escaping to the Wicklow Mountains but his disciples found him. Only when they prevailed upon him did he establish a monastery in this remote location. Although differing in style and ambition, these two saints formed a strong soul friendship.

While in his early 30s, Ciarán fell ill, probably from the plague, and died. The brothers laid his body in the little church until his anamcara could arrive from Glendalough. Kevin entered the church, dismissed the others in attendance, and, as he prayed, the beautified spirit of Ciarán returned to his body. The two engaged in conversation for a while then shared the Eucharist and exchanged gifts. After a brief time, Kevin emerged and declared that the body of his friend was ready for burial.

The wide-spread practice of soul friendship on this level has certainly diminished since the height of Celtic Christianity. Today many people benefit from meeting with a spiritual director but the relationship tends to be more one-directional than mutual. Accountability groups of different kinds are popular but they can’t always create an atmosphere conducive to more intimate sharing. While few may enter into traditional anamcara relationships, these other forms witness to the great power generated in direct human encounter for the purpose of spiritual development.

There is no substitute for being physically present with another person as a companion on the journey. Kevin made the arduous journey some 90 miles to Clonmacnoise and Ciarán’s spirit even re-animated his body so their friendship could be fully embodied.

But the mystical elements of this story suggest that there is something going on beyond the physical. After his death, Ciarán existed in a liminal space, a reality beyond that bound by space and time. This “virtual reality” invites us to imagine new possibilities for spiritual growth and engagement.

Advances in communication and information technology have enabled people to rekindle and deepen old friendships and to meet strangers they would never have encountered in the past. We have access to a great of diversity of voices and personal experiences, opening windows to the many ways that God is at work in the world. Not only does this have the potential to shape and enhance our spiritual lives, it also brings to our attention areas of great need. Pain inflicted by racism, for example, has always been with us but seeing videos of it in real time leads to greater boldness in calling it to account. Now we can act as friends to people we may never meet in person. Soul friendships between individuals are still important but now we also have the means to extend that friendship by caring for individuals and groups around the globe, the ones who have been too often overlooked, even the earth itself.

As Christianity encounters this brave, new world, the Celts have already shown us the way forward – listen respectfully to one another, hold each other accountable for the health of the community, and honor how we are all interconnected, now more than ever.

But I believe that the mystical elements of this story invite us to embrace a reality beyond that bound by space and time, a virtual reality, which offers new opportunities for spiritual engagement.

As an Amazon Associate, I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links.

Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

When referencing or quoting Godspace Light, please be sure to include the Author (Christine Sine unless otherwise noted), the Title of the article or resource, the Source link where appropriate, and ©Godspacelight.com. Thank you!