by Lynn Domina

I have been thinking about Jesus the teacher. He instructs many people, friends and enemies, the naïve and the sly, those hoping for grace and those hoping to outwit him. But as a good teacher once described a classroom, “There’s more teaching than learning going on here.”

We hear Jesus when he unrolls the scroll in the synagogue and reads from Isaiah, proclaiming good news. When he is finished, he rolls the scroll up, sits down, and says, “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.” His immediate listeners are first amazed and then angry—Jesus is nothing if not scandalous. We hear him telling stories, parables that seldom quite make sense. His immediate listeners (who are often his disciples) frequently misunderstand, interpreting his words literally rather than figuratively. They’re hearing the words, it seems, but they’re not comprehending the meaning.

So how do we understand Jesus? We hear his words and we observe his actions as they are described for us in scripture, but when Jesus repeatedly urges, “Let anyone with ears to hear listen!” he’s not talking simply about our physical capacity, though ears and eyes and hands and feet make for good metaphors throughout the gospel. Whether our physical senses are acute or dulled, understanding requires so much more than just perking up when sound waves strike our eardrums.

Understanding takes a lifetime of meditation with an open heart, thinking about what the stories in scripture might have meant then and what they might mean now, discerning how the lessons we each need to learn are revealed in our own lives. I’ve been thinking for years now about the story of the woman bent over in Luke 13: 10-17. When the story opens, Jesus is teaching on the sabbath. He sees the woman, interrupts his lesson, and heals her. Immediately, he’s criticized for performing work on the sabbath. His response is sensible—in emergencies, we’re permitted to work on the sabbath.

I have known women bent over, and we’ve probably all seen one or two. I have seen women bent at the waist, walking with canes, faces toward the ground, and I’ve tried to imagine what that feels like. I imagine the discomfort of looking up, the strain on your neck as you try to have a normal conversation with just about anyone. How uncomfortable it would be to try look toward the vast sky, the clouds, the moon, the stars. How painful it would feel when a child on a high swing calls, “Look at me, Grandma!”

I wonder whether there’s more to Luke’s story of Jesus. Isn’t healing the work of God just as much as praying is? I wonder whether healing isn’t a necessary component of Jesus’ sabbath teaching, different from the drudgery of much human work—scrubbing pots, tilling fields, counting up the cash of a day’s receipts. There’s the work of God, and there’s employment, the work we do to keep ourselves out of destitution, yes, but also to maintain our status, to acquire so many things that have so little to do with God. If we are each made in God’s image—the woman bent over, the disciples, the Pharisees—how does our work resemble God’s work?

The word “liturgy” is frequently defined as “the work of the people,” in the sense that the people participate rather than simply observe, but from what I’ve read recently, it might more accurately be translated as “work for the people,” work that benefits others. So curing the woman bent over is as liturgical as reading from scripture. It’s as liturgical as singing “Be Thou My Vision” or consecrating bread and wine or turning to one’s neighbor and saying, “Peace be with you.” It makes sense, then, that Jesus would stop preaching in order to heal. Both acts are works of and for the people.

Hearing Jesus, hearing deeply, with our entire beings, we understand that God’s work is our work, that permitting ourselves to heal and to be healed are acts of worship.

How did Jesus practice inclusiveness? I was faced with that question last week as I put together a resource list for our month on listening to the life of Jesus. One person complained because I included an author who is fairly conservative, excluding women from leadership and condemning LBGTQs. Another person complained because I included an author they thought was too liberal. It is very difficult for us to be inclusive across the full spectrum of Christian belief. Often in our attempts to include the excluded we alienate and therefore exclude the once included (hope that makes sense). Conservatives exclude progressives, progressives exclude conservatives.

While I was pondering on this today, I read this quote posted by my Facebook friend Kevin Bennett:

E. Stanley Jones, the missionary to India, once asked Mahatma Gandhi: ‘How can we make the Christian faith more native to India, so that it is no longer something “foreign” which is associated with foreign governments and seen as foreign religious practice, but it becomes part of life in India and a faith that makes a powerful contribution to building up this country?’

Gandhi replied: ‘Firstly, I would suggest that all Christians – missionaries and others – must start living more like Christ. Secondly, practise your faith without blurring it or watering it down. Thirdly, put special emphasis on love because it is the central point of Christian faith and therefore the decisive motivating force. Fourthly, study non-Christian religions with great sympathy, so that you can appeal to people of other faiths more effectively.’Ray Simpson (2002-08-01). A Holy Island Prayer Book (Kindle Locations 1001-1007). Canterbury Press Norwich. Kindle Edition.

And I thought: There it is. Jesus had friendships and relationships that seemed to span the spectrum of society and I suspect of religious beliefs. And I think that Jesus would have applauded Gandhi’s perspective.

- Live more like Christ. This is not an easy statement to understand or to follow. We have different ideas of what it means to live like Christ, but as I read the gospels what I see is in Christ love, compassion, generosity, and acceptance. Jesus did not turn his back on those who were considered unacceptable by his audience be they Pharisees, Samaritans, Gentiles, lepers or prostitutes, unless they turned their backs on him. One characteristic of Christ I love is the way he treated people who brought “sinners” to him for judgement. He always pointed back to the sin in their own lives. Acceptance not condemnation is the way of Christ. We are all called to work on the sin in our lives, not on the sin in someone else’s.

- Practice your faith without blurring it or watering it down. Jesus calls us to take our beliefs seriously and to live them out with confidence, grappling with the hard questions such commitment raises. As we do so we learn more of what it means to be a follower of Jesus and sometimes in the process our beliefs change.

- Put specific emphasis on love. Wow – if we all lived this one out we would not need the others. Love is the centre of Christian faith – love towards friends and enemies. There is no place for hate in Christian faith. Our response to those who think differently should be to reach out in love, to seek to understand their perspectives and help them understand ours.

- Study non-Christian religions with great sympathy so that you can appeal to people of other faiths more effectively. I would expand this to say “study Christians with other faith perspectives with great sympathy too” and be prepared for the fact that you may need to change as much as they do. Christianity is about unity not uniformity. When those outside the faith see that we are able to love each other across the barriers of race, gender and sexual orientation they will truly be impressed and willing to listen to our message. I suspect that was one of the reasons they were so open Jesus. He welcomed them, questioned them and allowed the Holy Spirit to work in their lives to help them understand truth.

What is your response?

Watch the video below. Think about the way you live your life and represent Christ. Are there people you exclude by your attitudes and beliefs? Are there times you might have excluded Christ in the process? Are there ways you could become more inclusive? What response is Christ asking of you today?

by Jeannie Kendall

For much of my professional life I was paid to listen. Working as I did, as a counsellor, I had the enormous privilege of listening to many people. For some, the words came easily. For others, it was a painful struggle, each word hanging in the air like a bubble which I dare not catch too soon lest it disappear. At times I had the great honour of hearing the words “I have never told anyone this” – and at such times I knew that I was on holy ground.

My granddaughter, in contrast, is six and has no difficulty in talking. She tells me about her day, her friends, what she wants to do next and, currently, what she would like for Christmas. Life for her, it seems, is one long glorious self-expression.

What struck me recently though is that she very often prefaces her next soliloquy with “Can I tell you something?” Loving her as I do, I always answer yes, and she begins.

I’ve been reflecting on this simple phrase. The power of telling someone something is enormously significant. So many of us, for different reasons and in varying contexts, have been told, directly or indirectly, not to tell. Sometimes this is catastrophic, as when abusers silence others with threat or inappropriate and disempowering secrecy. Sometimes it is less obvious but still damaging: where the unspoken expectation of a family is that things are not spoken of: feelings are to be silenced, shame unvoiced.

One of the greatest gifts we can give another person is to allow things to be told: to create a safe and non-judgemental space where the fears and pain can be shared without reprisal, where we can find a voice for the unspoken things which sit achingly in our soul. Such trust, for some, takes time and can be fragile but it is inexpressibly precious. When a friend asks – directly or indirectly and it is often the latter – “Can I tell you something?”, we are being given the opportunity to give a rare and valuable gift which has the potential for healing.

The Psalms reveal that the writers had found a level of friendship with God that made such telling possible. Fear, anger, loneliness are poured out without edit with the implied assurance that God is listening, that His answer to “Can I tell you something?” is always an eager “Yes, of course, I have been longing for you to”. In friendship we model, imperfectly, this open welcome for our deepest emotions. For some, this human listening is an important step in discovering this: to experience human, imperfect acceptance models the possibility of One who hears and understands perfectly. We may need to experience the seen to begin to trust the unseen. For many of us, someone who gently and consistently listens allows us the first tentative steps towards a journey of trust, of daring to expose the fragility and vulnerability at lies within. In the end though, our gifts of welcoming friendship always point to an eternal listening Love which is always waiting readily for our halting self-disclosure.

Jeannie Kendall is a pilgrim who has travelled several public paths: teaching, running a community coffee shop and counselling work and, more recently and currently, a Baptist minister. Her private paths are as a questioner who loves words and pictures. She lives in Surrey with her husband and has two grown up children and 2 grandchildren.

watercolour by Dave Baab

The Gospel of Mark records a busy first week of ministry for Jesus (Mark 1:14-34). Jesus announces the “good news of God” and calls disciples. He heals a man with an unclean spirit and many other people, including Simon’s mother-in-law. He casts out demons. He teaches in the synagogue on the Sabbath.

The next morning, “while it was still very dark, he got up and went out to a deserted place, and there he prayed” (Mark 1:35).

Simon and the other brand new disciples hunt for him. When they find him they tell him that everyone is looking for him, presumably to ask for more healing. Instead of jumping up and going back with the disciples to the village where they were the day before, Jesus replies, “Let us go on to the neighboring towns, so that I may proclaim the message there also; for that is what I came out to do” (Mark 1:38).

Jesus’ time of prayer in the dark morning gave him a renewed sense of his purpose. He was able to say “no” to other people’s agendas because he knew what he “came out to do.” I long to have that kind of clarity about my purpose, so I wish the Gospel writer had recorded more details. I have so many questions about this incident.

I wonder what Jesus was thinking and feeling when he talked about going on to the neighboring towns to proclaim the message. Was he frustrated that so many people came to him to be healed the day before rather than wanting to hear more about the good news of God? Did he want to go on to the other towns so he could get back to his ministry of preaching? Or did he view his healing ministry as a part of proclaiming the good news? Did he simply want to scatter the seed widely, both by preaching and healing, so it was important to move on to new villages? I admit that the answers to these questions wouldn’t have a huge impact on my own life and ministry, but I’m curious.

I have other questions that are more relevant to my desire to hear God’s guidance clearly. I wonder about what happened in the very early morning in that deserted place. Did Jesus hear the voice of his Father giving new instructions? Maybe he heard, “You did a lot of healing yesterday in only one town. You need to go to other towns and focus on proclamation rather than healing.”

Perhaps being alone, away from the clamoring crowds, helped Jesus recover his original sense of call. He says, “This is why I came out,” and perhaps some time alone enabled him to evaluate the previous week in the light of his resolve. Maybe solitude and prayer renewed his clarity about his goals.

I wonder if maybe the time alone with his Father in prayer was simply pure joy. Maybe he knew his calling clearly and felt that the days before had been significant and purposeful. Maybe he just wanted a few peaceful moments to enjoy intimacy with his Father.

I also wonder if being in a deserted place, enjoying the beautiful world he helped create, gave him a sense of restored purpose. It was full dark when he got there, but perhaps the birds’ raucous dawn chorus began while he was praying. Perhaps a sliver of light on the eastern horizon announced the arrival of the sun and revealed the trees and green hills of Galilee. Perhaps the beauty of what he could see and hear reminded him that he came to earth to restore the whole created order to its original design.

I don’t want to say that time alone at dawn in prayer is the only way to gain or regain a clear sense of the goals and purpose God has for us. But I do think Jesus provides a model that combines several components: intimacy and joy in God’s presence, listening to God’s guidance, and enjoying the beauty of the earth that came from the mind and Word of God, and which now needs to be restored back to its intended purpose. I want to listen to the pattern of Jesus’ life and learn how to draw near to God more often and more fully.

Our theme this month on the Godspace Community Blog is “listening to the life of Jesus”. As Christine Sine and I reflected on this theme we both had favorite authors we thought fit well, and so this month we have two “Featured Authors”, Kenneth Bailey and N.T. Wright.

Today I want to share a reflective review of N.T. Wright’s book, The Lord and His Prayer. Wright opens up “The Lord’s Prayer” by looking at what it must have meant for the disciples who first heard it. Taking the prayer line by line, Wright puts the words squarely in their historical context. But his purpose is not to leave them there. Wright brings the past forward into our present, drawing us into God’s future and our future with Him. While the prayer reveals to us the purposes of God in Christ, it also shows us our intended relationship to those purposes and offers a clear and grace-filled invitation to enter into the Kingdom purposes of God.

Today I want to share a reflective review of N.T. Wright’s book, The Lord and His Prayer. Wright opens up “The Lord’s Prayer” by looking at what it must have meant for the disciples who first heard it. Taking the prayer line by line, Wright puts the words squarely in their historical context. But his purpose is not to leave them there. Wright brings the past forward into our present, drawing us into God’s future and our future with Him. While the prayer reveals to us the purposes of God in Christ, it also shows us our intended relationship to those purposes and offers a clear and grace-filled invitation to enter into the Kingdom purposes of God.

Our Father: I easily grasp these words and find comfort and love. Here is a God who is not far off in some distant heaven but rather one who, in love and grace, draws near to me. But I also resonate with Wright’s words, “It is no doubt true, here as elsewhere, that the end of all our striving will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time,” and “But it will take full Christian maturity to understand…what those words really mean.” (p.12). At once there is a peace in the presence of Father, but there is also a mystery I do not fully understand. The God of the entire universe calls me Child and invites me to call him Father. At the very beginning of this prayer, for me, is a sense of invitation into the mystery and love of God.

Thy Kingdom Come: Perhaps one of the reasons I so enjoyed this book is that it touches on several central features of my own beliefs. God’s Kingdom is coming, has come, and is present right now. Wright demonstrates how Jesus lived out this coming kingdom in fulfillment of Isaiah’s prophecy (Is. 40-55). But unlike many people occupying seats in the church on Sunday, Jesus didn’t call us to rest on his laurels. Jesus calls us to step out in faith and continue the work of ushering in the Kingdom. For many this is limited purely to evangelism, and when it does take on a more social tone, it’s often centered on the agendas of the political right or political left. But for Jesus the Kingdom of God was not right or left; it was central. He would not allow his Kingdom-focus to be sidetracked by the zealots, even though their message contained some truths of God’s Kingdom. Nor would he side with the Pharisees, even though their heart was to preserve the truths of the Law without compromise. Jesus was not willing to compromise, but he was also unwilling to place law above love.

For Jesus, “Thy Kingdom Come, Thy will be done” meant following the heavenly leader and exposing the deceptions and confusion clouding the thinking of all political and religious parties. “Thy Kingdom” means God’s Kingdom, not ours. To pray “Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” means to relinquish my hold on “reality” with all the various and assorted assumptions it contains and allow God’s Kingdom to reign in my mind as well as my heart, then walk out the door and live it!

Wright continues this idea of not just saying the prayer but living into it as he approaches the issue of daily needs. “Give us this day…” Our daily needs are important to God. Wright correctly states that, “…the promise of the Kingdom includes those needs, and doesn’t look down on them sneeringly as somehow second-rate.” (p. 43) God cares about us and intends for us to live in this world, a world created by God; therefore our daily needs are needs created in us by God and we look to Him to meet those needs.

But going beyond this very personal request, Wright challenges us to realize the deeper need of the world. To pray this prayer and not be aware of the millions around the world in need is to miss the whole focus of the prayer itself – “Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done…”. If this is indeed our prayer then we must not only support causes of those in need but also empathetically enter into that need with the love and grace of God. It’s too easy to send money. It’s quite another thing to befriend the poor, the orphaned, and those in prison.

Wright ties these ideas together in the Eucharist/Communion as we come together to share at the Lord’s Table. Jesus is the Bread of Life, not just for me but for the whole world. To bring in my mind and heart a brother or sister in need to the table of the Lord should be a natural thing. Jesus gave himself “for the life of the world” (Jn. 6:51). When I receive the bread and cup I must remember this tremendous gift is not just for me but for those still imprisoned in darkness, longing for the light.

Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who have trespassed against us. This is a terrifying line. Jesus is teaching us to ask God to forgive us in the same way that we forgive others. If it wasn’t obvious earlier in the prayer, it is now; we are not just praying to God, but through our prayer we are also committing to becoming part of the answer to this prayer as it’s prayed by our neighbors. “Forgive me God, but forgive me in the same way, to the same degree, that I forgive those around me.” I am, in effect, praying, “forgive me to the extent that I enter into your kingdom purposes here on earth.” I am accountable for my actions! When I pray in this way I’m saying that yes, grace is free, but once I received it, I enter into a whole new reality – the reality of God’s Kingdom, with all its joys and responsibilities.

I cannot end without mentioning Wright’s inclusion of “Jubilee” in this prayer. All that is prayed speaks to the Jubilee of God – canceling of debts, forgiveness, return to the family land. Each phrase speaks of how this Jubilee is lived out through the power and presence of God in our lives.

Jubilee means that I can no longer really speak of “my faith” but rather “Our Faith”. While very personal, God’s Kingdom purposes are intended for the whole world. To ignore the fullness of this prayer by making it merely a personal petition flies in the face of Jubilee and our connectedness to others. Ultimately, to truly know God as “Father” is to fully embrace God’s purposes for us and the entire world. Jubilee indeed sets us free by turning the world right side-up, making God central rather than living with humankind at the center and God as our servant.

For me, this prayer and this book is a perfect way to begin the month “Listening to the life of Jesus.” To understand Jesus’ prayer more fully, both in the context in which he taught it and as it applies in our lives and world today, draws us to the heart of Jesus. Once there, we must decide how we will respond.

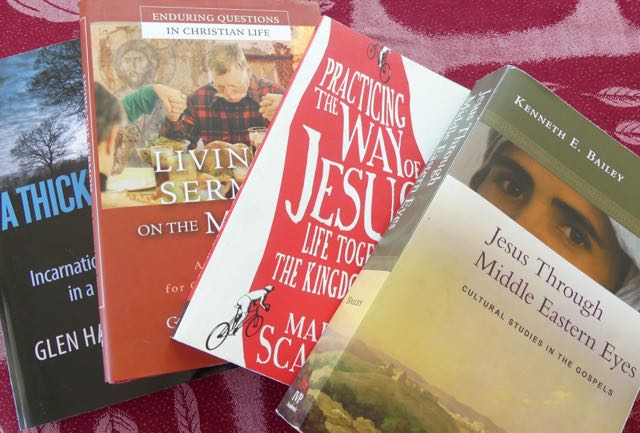

Over this next month we will be focusing on listening to the life of Jesus. Here is a short list of books that we have found helpful in our quest. We have chosen theologians and practitioners from a variety of perspectives and drawn from suggestions given by several of our authors. However we would love to expand the list – you may note for example that all these authors are white males! Who are the women and those of other ethnic backgrounds that speak to us from the life of Jesus? So often we feel that we jump straight from the birth of Jesus to his crucifixion and death and live more through the words of Paul then the life of Jesus. What books would you recommend that help us learn from the life of Jesus and the gospel stories?

Bailey, Kenneth: Jesus Through Middle Eastern Eyes.

Bock, Darrell L.: Recovering the Real Lost Gospel: Reclaiming the Gospel as Good News.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich The Cost of Discipleship.

Bourgeault, Cynthia: The Wisdom Jesus: Transforming Heart and Mind–A New Perspective on Christ and His Message

Keller, Timothy: The Prodigal God.

Kraybill, Donald: The Upside Down Kingdom.

Newbigin, Lesslie: The Gospel in a Pluralist Society.

Nouwen, Henri The Return of the Prodigal Son.

Scandrette, Mark: Practicing the Way of Jesus.

Stassen, Glenn: A Thicker Jesus.

__________: Living the Sermon on the Mount: A Practical Hope for Grace and Deliverance

Stott, John R.W.: Life In Christ: A Guide For Daily Living.

Vanier, Jean: Drawn Into the Mystery of Jesus Through the Gospel of John

Wright, N.T. : The Challenge of Jesus.

_________: The Lord and His Prayer

You might also like to browse back through some of the posts in a previous series Following Jesus What Difference Does it Make.

Tag, You’re It!

It’s August, which means that Christine Sine has officially retired as active Co-Director of Mustard Seed Associates // Godspace and handed the reigns over to Andy Wade. Christine and Andy agree it’s been an extremely smooth transition.

It’s August, which means that Christine Sine has officially retired as active Co-Director of Mustard Seed Associates // Godspace and handed the reigns over to Andy Wade. Christine and Andy agree it’s been an extremely smooth transition.

What does this mean? We’ll be writing more about that in our August newsletter but, in short, it means Christine no longer needs to worry about the day-to-day operations and administration of the organization and can instead focus on writing and workshops. If you’re a regular reader of our Godspace Community Blog, or follow any of our pages on Facebook, you likely won’t even notice the change.

Godspace Community Blog

Exciting things are happening on the Godspace Community Blog. We’ve just passed the 50 contributor mark with women and men from over nine countries and a wide variety of traditions contributing their perspectives and insights.

This month on our blog we’ll continue our series on listening, with the theme, “Listening to the Life of Jesus”. We’ll also be featuring two authors and a couple of classic books this month. It should be another insightful and inspiring month.

Would you like to do more than just read the blog? Check below for how you can join our growing community of writers and artists.

Godspace Featured Authors for August

N.T. Wright: Former Bishop of Durham in the Church of England and one of the world’s leading Bible scholars, Wright is now serving as the chair of New Testament and Early Christianity at the School of Divinity at the University of St. Andrews. For twenty years, Wright taught New Testament studies at Cambridge, McGill, and Oxford Universities, and he has been featured on ABC News, Dateline, The Colbert Report, and Fresh Air.

Kenneth Bailey (1930-2016): An author and lecturer in Middle Eastern New Testament studies and an ordained Presbyterian minister, Bailey also served as Canon Theologian of the Diocese of Pittsburgh of the Episcopal Church, USA. He held graduate degrees in Arabic language and literature, and in systematic theology, and his Th.D. was in New Testament. He spent forty years living and teaching New Testament in Egypt, Lebanon, Jerusalem and Cyprus.

Join the Expanding Community on Our Godspace Community Blog!

We’re always looking to diversify and expand our band of poets, artists, and writers. This is a great time to join with us as the seasons change and we continue exploring the spiritual discipline of listening.

We’re always looking to diversify and expand our band of poets, artists, and writers. This is a great time to join with us as the seasons change and we continue exploring the spiritual discipline of listening.

Share your voice and let the world hear your unique perspective. We take blog submissions (600-800 words with a picture), poetry, prayers, liturgies, and artwork. We want this to be your place to explore the intersection of faith, imagination, and sustainability.

Drop us an email and let us know you’d like to find out more.

Top Godspace Posts in July

- My Top Ten Ideas for Cultivating Hospitality in the Front Yard – Andy Wade

- Meditation Monday: Draw Your Circle Around Me, Lord – Christine Sine

- Chasing Hilda – Rev. Brenda Griffin Warren

- Discovering the Rule of St. Columba – Greg Valerio

- Radical Hospitality: the Way of the Celts – Rodney Newman

As an Amazon Associate, I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links.

Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

When referencing or quoting Godspace Light, please be sure to include the Author (Christine Sine unless otherwise noted), the Title of the article or resource, the Source link where appropriate, and ©Godspacelight.com. Thank you!