by Louise Conner, originally posted on the Circlewood blog The Ecological Disciple here: The Art of Creation: “Back” and Its Stories

For the past 20 years, Isabella Kirkland has documented flora and fauna in danger of extinction through paintings that combine techniques of Old Dutch Masters paintings with scientific accuracy learned through past experience as a taxidermist and current experience as a Research Associate at the California Academy of Sciences. Kirkland measures, photographs, draws, and observes firsthand (using live or preserved materials) the subjects of her paintings and then re-creates them with oil paint in anatomical accuracy and true-to-life scale. Each painting takes at least a year for her to complete, and each creates an awareness of the important of biodiversity and our current environmental problems.

Her Taxa collection includes six paintings that, combined, depict almost 400 species whose existence has each been deeply affected by human actions. Kirkland began working on the series after reading a list of the 100 most-endangered species in the United States.

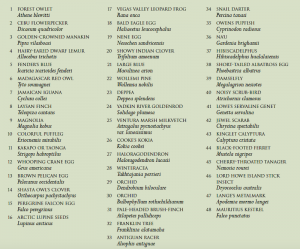

Each painting in Taxa (the plural form of “taxon,” meaning order or arrangement), includes species of animals and plants who have been affected in particular ways by humans. The painting Gone features plants and animals that have become extinct, Trade—species that are harvested in the wild and sold through both legal and illegal markets, Collection—plants and animals that are treated as decorative objects, Ascendant—non-native species that have been introduced to the U.S. and are increasing and overtaking native species, Descendant—endangered species, and finally, the painting which I share within this post, Back—species which were either nearly extinct and have rebounded or were thought to be extinct, and have been rediscovered. In other words, species which have come back from extinction.

The forty-eight species in still-life Back have rebounded through sustained attempts to reintroduce them to their original habitats, and at times through sheer resilience.

The forty-eight species in still-life Back have rebounded through sustained attempts to reintroduce them to their original habitats, and at times through sheer resilience.

Each of these species has its own story, many of which demonstrate the power humans have to change the outcome for species if research and sustained effort are brought to the work. Some in the painting, such as the bald eagle represented by the egg labeled #18, are poster children for regulation, education, and success; the stories of many others are less well-known.

Consider the Owens Pupfish (#35 in the picture). These natives of California’s Central Valley from the Owens River and associated sloughs and marshes, have an amazing survival story. During the California Water Wars of the 1920’s and 30’s, the diversion of water from the Owens River to the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area eliminated most of the pupfish’s habitat. Introduced species such as largemouth and smallmouth bass, brown trout, bluegill, crayfish, and bullfrogs further decimated the population. By 1948, the Owens Pupfish was thought to be extinct. Upon its rediscovery, pools were built and barriers erected to keep out nonnative predatory fish, but in 1967 it was listed as endangered, and in 1969, the pools which provided its habitat almost completely dried up due to weather causes. Certain employees of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife were aware of the urgent crisis and raced to an area called Fish Slough with buckets, nets, and aerators in an urgent effort to save the fish. They put 800 of the survivors into mesh cages in a nearby pool, intending to move them to better sites the following day. But, before leaving for the day, one worker, Phil Pister, checked on the fish and realized they were dying from a lack of oxygen due to poor placement in the water flow. With just two buckets on hand, he quickly gathered as many of the still-living fish as he could fit into the buckets and moved them to nearby pools with more aeration. The species survived—because of intense dedication, passion, and hard work (plus a dash of luck). In this article, Phil Pister tells this story in detail, and also gives an overall picture of the importance of saving those species that are at risk.

As Isabella Kirkland herself says,

“In-depth study of a single species can yield a world of information: each life cycle is deeply entwined with that of others in its community. The more we learn about the intricacies of one organism and its ecosystem, the more we can see the limits of our current knowledge. The more we discover, the more we comprehend our responsibility for every other living thing.”

The Owens pupfish is just one of the species portrayed in Back—and its story is just one example. Each species has its own story. Some of those stories involve human care and intervention that can inspire us to act in similar ways. The Franklin tree (#32) was preserved by a man named John Bartram who collected seeds that grew into the only Franklin trees then still in existence and which all Franklin trees are now descended from. The dedication of Japanese ornithologist Hiroshi Hasegawa has brought back the once-believed extinct short-tailed albatross (#38). The large blue butterfly (#21) became extinct in Britain despite conservation efforts until the research of scientist Jeremy Thomas and associates was able to pinpoint the causes of its demise (an introduced species of red ants that instead of having a cooperative relationship with the butterfly as the native species had, instead attacked and killed them). As a result of this knowledge, the blue butterfly of Sweden was successfully introduced into an intentionally and carefully recreated habitat that met the needs of the butterfly, needs which had been discovered through this research.

Reading these stories brings home the danger of thinking that “small” actions have no real consequences in the bigger world. For instance, releasing an aquarium fish into the wild may seem like no big deal, but it can have effects on the natural populations that we may not foresee. Planting a nonnative species can devastate an ecosystem one species at a time if that nonnative species happens to be invasive or predatory to the native species already present. On the flip side, eliminating detrimental species can have a positive ripple effect as the native flora and fauna become reestablished and planting something that can create habitat for a struggling species in your area can be an important part of rebuilding the health of a particular species, and even by extension, an ecosystem. Through our presence, we change our surroundings; by caring and learning, we can make those changes positive for our environment, rather than negative.

If you want to find out more about some of the species in Back, check out the links included here: Forest Owlet, Cebu Flowerpecker, Madagascar Red Owl, Jamaican Iguana, Kakapo, Antiguan Racer, Lord Howe Island Stick Insect, and Lange’s Metalmark. You can also search for the other species listed in the painting key above.

What can be learned from the type of careful observation found in the art of Isabella Kirkland? Are there actions you can begin or end that can help foster the struggling plants and animals in the area where you live?

To see the rest of the Taxa paintings and more of the work of Isabella Kirkland, visit her website.

Feel free to contact Louise directly at info@circlewood.online.

Explore the wonderful ways that God and God’s story are revealed through the rhythms of planting, growing, and harvesting. Spiritual insights, practical advice for organic backyard gardeners, and time for reflection will enrich and deepen faith–sign up for 180 days of access to work at your own pace and get ready for your gardening season.