I have lived with uncertainty for so long. I never know how much energy the next day will bring, whether I will be able to speak, to move out of bed, to get dressed, to self-propel my wheelchair, to feed myself, to listen to a friend, to prioritise playing with paint and print and photos.

I am better than I used to be at accepting the temporary limits my body imposes, and at adapting to the limits that might shift at any moment of the day, imposing rest, or demanding a complete cessation of everything in the collapse which a seizure brings. But sadly, I must confess I am not a patient person. My inner perfectionist stamps her foot, my inner critic screams venomously about my inadequacies, my inner taskmistress ominously cracks her whip. My neglected artist child gears up for a full-on tantrum. And yet, I know that the counterbalance to this internal self-punishment is to look out – up or down, it doesn’t matter – and flex my rejoicing muscles. For there is always something to be grateful for in my present, something praiseworthy will always be right in front of me. God is always in my details. Presence is always assured, and this moment of connection with thanksgiving is always certain and concrete.

I am better than I used to be at accepting the temporary limits my body imposes, and at adapting to the limits that might shift at any moment of the day, imposing rest, or demanding a complete cessation of everything in the collapse which a seizure brings. But sadly, I must confess I am not a patient person. My inner perfectionist stamps her foot, my inner critic screams venomously about my inadequacies, my inner taskmistress ominously cracks her whip. My neglected artist child gears up for a full-on tantrum. And yet, I know that the counterbalance to this internal self-punishment is to look out – up or down, it doesn’t matter – and flex my rejoicing muscles. For there is always something to be grateful for in my present, something praiseworthy will always be right in front of me. God is always in my details. Presence is always assured, and this moment of connection with thanksgiving is always certain and concrete.

The most accessible way for me to reconnect with the Giver is through my contemplative photography practice acts of daily seeing. It reminds me where I am rooted, not just through its subject matter, which often focuses on what I see as the glory in the things others overlook, but also through my breath, through my technical precision or experimentation, through my attentiveness to waiting to receive the moment to press the shutter, through a deliberate openness to Thy Will be done in this moment.

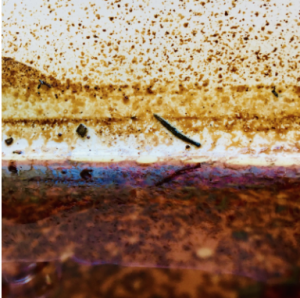

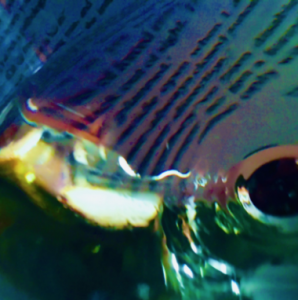

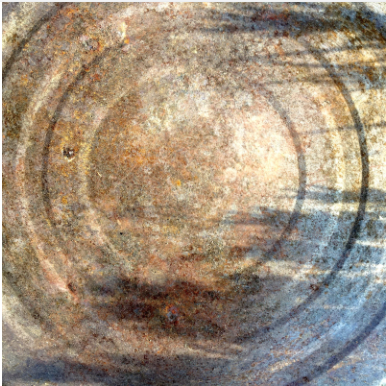

The images I receive in this way often reflect my interest in obscurity, in layers, in essences, in what is unclear, in Wabi Sabi, in ‘through a glass darkly’. Out of my contemplation of these themes, many of the photos I offer up as contemplative tools for others use distinct distortion techniques (like using macro or zoom lenses, distancing or foreshortening, removing context, and using strange angles). I suspect I do this in order to make the everyday unrecognisable, in order to re-appreciate the beauty and the mystery of what is before me, in order to encourage the looker to take time to see beyond the surface. I’m not trying to hide the Godhead in mystique, but for each image to create a pause long enough to show off the God who is so much more than I ordinarily perceive. I know my images often frustrate those whose first instinct is to ask ‘what is it?’ Yet I have found that when I ask this question, my need for such certainty, clarity, control and order normally ensures I miss the point of so much that resides in God’s Kingdom.

The images I receive in this way often reflect my interest in obscurity, in layers, in essences, in what is unclear, in Wabi Sabi, in ‘through a glass darkly’. Out of my contemplation of these themes, many of the photos I offer up as contemplative tools for others use distinct distortion techniques (like using macro or zoom lenses, distancing or foreshortening, removing context, and using strange angles). I suspect I do this in order to make the everyday unrecognisable, in order to re-appreciate the beauty and the mystery of what is before me, in order to encourage the looker to take time to see beyond the surface. I’m not trying to hide the Godhead in mystique, but for each image to create a pause long enough to show off the God who is so much more than I ordinarily perceive. I know my images often frustrate those whose first instinct is to ask ‘what is it?’ Yet I have found that when I ask this question, my need for such certainty, clarity, control and order normally ensures I miss the point of so much that resides in God’s Kingdom.

Still, I don’t underestimate the acute discomfort that can come when I look at something and I don’t know what I’m supposed to think. I can feel my whole body tense and revolt in response to the brain’s panic when it can’t recognise, name, catalogue, or signify what is in front of me. I feel stupid. I feel left out of the ‘inner circle’, the cognoscenti, those who must surely understand everything. I can experience a deeply painful heart-longing for direction from the artist: what was ‘intended’ when they made this image? Did they think of how it might feel to not ‘get it’? Very quickly, such a lack of understanding or clarity can bring me to a lonely place, making me feel utterly isolated in my confusion.

Still, I don’t underestimate the acute discomfort that can come when I look at something and I don’t know what I’m supposed to think. I can feel my whole body tense and revolt in response to the brain’s panic when it can’t recognise, name, catalogue, or signify what is in front of me. I feel stupid. I feel left out of the ‘inner circle’, the cognoscenti, those who must surely understand everything. I can experience a deeply painful heart-longing for direction from the artist: what was ‘intended’ when they made this image? Did they think of how it might feel to not ‘get it’? Very quickly, such a lack of understanding or clarity can bring me to a lonely place, making me feel utterly isolated in my confusion.

So often I find cry out to the Great Artist for the same kind of direction. I feel I am so poor at discernment, and even though I try to practice listening more intently through the making of a weekly sabbath lectio collage, hearing a single ‘word’ with clarity from amongst my complicated brain chatter is more than challenging. And even if I am able to distill out a word or phrase to mull over visually as well as prayerfully during the week that follows, I frequently find myself journalling to ask God, ‘Which direction should I face? Which of the hundred ideas I have before breakfast should I follow? And what about the hundred ideas I had yesterday? And the day before that?…’

As a result, I can feel rudderless. I can feel abandoned. Thus I have to remember again: I am powerless. What God is inviting me to do is to let go of my driven attempts at forcing the pace from my own willpower: God is calling for me to let go deliberately and completely. In letting go, I notice that the zeitgeist of anxiety around COVID-19 has crept under my bedroom door and is infecting me, reigniting those depressive tendencies in me that wait to rear up at the slightest provocation. And yet: I am shielded and privileged and white and prosperous (in practically every relative sense); I am able to read and write; and I own technology which allows me to access this virtual space here at Godspace, which means access to a gifted, loving, generous community who provide me with a safe place to speak what is on my heart. As I let go of all this, I can hear my heart whisper: What of all those who are voiceless in any or all of these ways? How do I help them to be heard?

As a result, I can feel rudderless. I can feel abandoned. Thus I have to remember again: I am powerless. What God is inviting me to do is to let go of my driven attempts at forcing the pace from my own willpower: God is calling for me to let go deliberately and completely. In letting go, I notice that the zeitgeist of anxiety around COVID-19 has crept under my bedroom door and is infecting me, reigniting those depressive tendencies in me that wait to rear up at the slightest provocation. And yet: I am shielded and privileged and white and prosperous (in practically every relative sense); I am able to read and write; and I own technology which allows me to access this virtual space here at Godspace, which means access to a gifted, loving, generous community who provide me with a safe place to speak what is on my heart. As I let go of all this, I can hear my heart whisper: What of all those who are voiceless in any or all of these ways? How do I help them to be heard?

Perhaps resisting asking ‘what is it?’ of an image seems a strange place to start living out the values of the Beatitudes, but something in me is definite that practicing glimpsing and acknowledging the presence of the Holy in the midst of an unrecognisable mess might just provide the smallest of openings for the Spirit to slide in – and then, God knows, anything might happen. And so if I listen to that urge, rather than following the desire to impose what I define as order and ‘the answer’, I might get close to obeying the commission I sense God is asking me to fulfill: making an epiphany of the ordinary – showing the messy, dirty, unlovely ordinary as belovedly sacred again – wherever and whenever I look.

We look with uncertainty

beyond the old choices for

clear-cut answers

to a softer, more permeable aliveness

which is every moment

at the brink of death;

for something new is being born in us

if we but let it.

We stand at a new doorway,

awaiting that which comes…

daring to be human creatures,

vulnerable to the beauty of existence.

Learning to love.

‘we look with uncertainty’

All images by Kate Kennington Steer, used with permission.

1 comment

This is beautiful and powerful. Thank you so much for sharing your journey.