Today’s post is written by Chris Holcomb, a former MSA intern currently living in Boone, NC, where he works as an insurance agent for Bankers Life, volunteers as a community metrics intern for BALLE, and occasionally blogs at thellamaandthecow.wordpress.com. He and his wife are enjoying learning what it means to slow down and appreciate life in the beautiful Appalachian Mountains.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

As I referenced in my Back to the Basics post exploring poverty, one of the formative experiences in my life was a mission trip to Costa Rica where I did very little to aid the people of Costa Rica, but they did much to help me. It was there that I first witnessed in a radical way the potential for disconnect between income and happiness or gratitude. Some of the happiest and most gracious people I have ever met have lived in trailers, dirt-floor homes, and homeless shelters.

Because of this, it has always been slightly disconcerting to me as an economics student that my academic discipline is based partially on the relationship between money and utility (a measure of happiness or satisfaction) and the principle that “more is always better.” While I have never purported that there is no relationship between money and happiness or that “less is always better,” my life experiences have taught me that there are often much more important things for my own personal satisfaction in life than just my wealth or possessions. I believe that most economists, if you asked them about their personal experiences, would say the exact same thing as me, and yet we continue to religiously watch the daily rise and fall of the stock market, hold up per capita GDP as the primary barometer for our country’s health, and read sensationalist articles telling us that “Money Can Buy Happiness.”

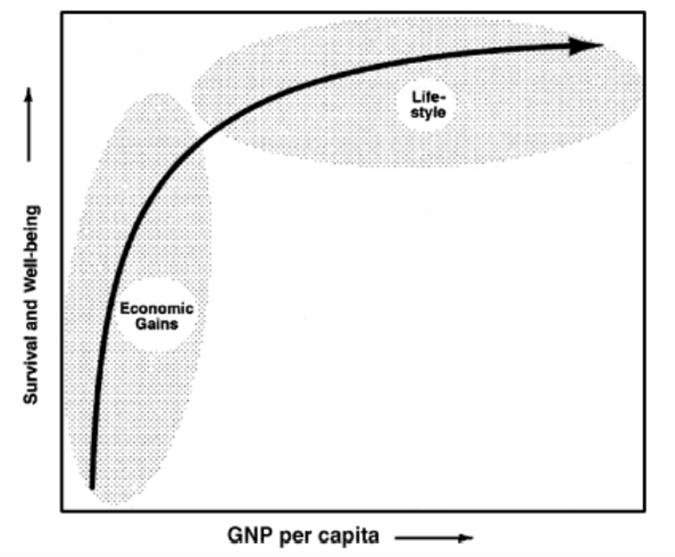

Thankfully, there is a growing movement to promote alternatives to GDP (Such as: the Genuine Progress Indicator, the Human Development Index, the Ecological Footprint, The Happy Planet Index, and Gross National Happiness), and many before me have given this movement ammunition by studying well-being at both personal and national levels. A good synopsis of the breadth of research on this topic can be found in Alois Stutzer and Bruno S. Frey’s report here. It has been pretty widely established by now that the relationship between per capita GDP and a country’s well-being (as measured by subjective surveys) is logarithmic, that is, countries see dramatic increases in well-being as GDP initially rises, but each further increase in GDP brings about progressively smaller increases in well-being. This makes sense; a five dollar bill is worth less to a millionaire than a beggar. The following chart from Ronald Inglehart (simplistically) further illustrates this transition: that after basic needs are met through economic growth, individuals do not see as much gain in well-being from improvements in income and “Non-economic aspects of life become increasingly important influences on how long, and how well, people live.”

Those of us Westerners who don’t have to worry about where our next meal is going to come from are living in this lifestyle sphere, and it is this society that Christine writes for in her post, “What Happiness Habits Should We Develop?” When considering topics for my senior economics thesis, I decided to build upon all of this prior research and put Inglehart’s hypothesis under a microscope. I knew that the things Christine’s post mentions had been more important than money for my own personal happiness, but I wanted to see what the data had to say to either confirm or deny my instincts about their application at a national level.

While I was slightly limited by my lack of a PhD and access to any data that wasn’t free, my research was subject to critique by both my peers and superiors and, I believe, representative of the highest achievable academic quality at the undergraduate level. I began by analyzing whether there really was a difference between high and low-income countries in terms of what makes them happiest. Setting $8,500 in per capita GDP as the cutoff point between low and high-income, I found that there were indeed massive differences between the two groups. The 5 most important variables for the collective well-being of a low-income country were:

1. Subjective Opinion of Health

2. Level of Freedom of Choice and Control

3. Lack of Materialistic Priorities

4. Per Capita GDP

5. A Low Unemployment Rate.

For High-Income Countries, the top 5 were:

1. Subjective Opinion of Health

2. Lack of Materialistic Priorities

3. Importance Given to Leisure Time

4. Level of Confidence in “the churches”

5. Having Fewer Working Hours

While subjective assessments of health and levels of materialism remained important in all countries, the other 3 variables for each group were markedly distinct from each other. This result seemed to justify my decision to look more selectively at just high-income countries for analyzing national well-being, as most previous analyses had lumped all countries together for their tests.

As I analyzed this subset of countries further, I explored many different questions and came away with two more observations that are worthy of sharing here. The first was that while increases in GDP do still result in increased well-being among high income countries, this effect almost entirely disappears when the decreases in unemployment and annual working hours that typically accompany GDP are taken into account. This suggests that if we really want to increase our well-being as a country, we ought to decrease our average working hours per person, allowing for more leisure time and more employment.

The second observation had to do with our views on the government’s role in environmental protection. It seems that there is a stark contrast between those who are willing to spend personal income for environmental protection and those who would like the government to do so. Citizens willing to spend their personal incomes typically reside in less wealthy countries that place more emphasis on leisure time, while citizens encouraging their government to stop pollution typically reside in higher income countries with lower ecological footprints and less trust among the population.

Overall, I must say that while not everything was exactly as I expected, my research did little to sway the priorities that I had learned from life prior to my semester of statistical analysis. Whether we look at psychological studies, econometric analysis, or personal experience, it seems that if we really want to be happier both individually and collectively, we must follow Christ’s example: ensure that the poor, widowed, and orphaned have the basics they need for survival; realize that slavery to a job, chasing after increased incomes, and the accumulation of material possessions is an ultimately hollow pursuit; and cultivate strong relationships that engender trust with those around us as a Church body united in Christ.

My full paper is available for free download here.