by Derek Olsen

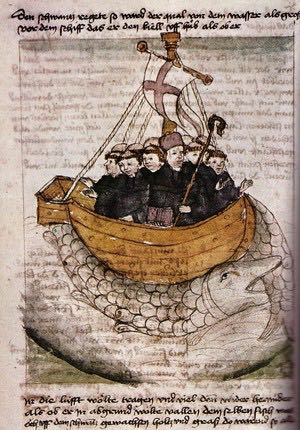

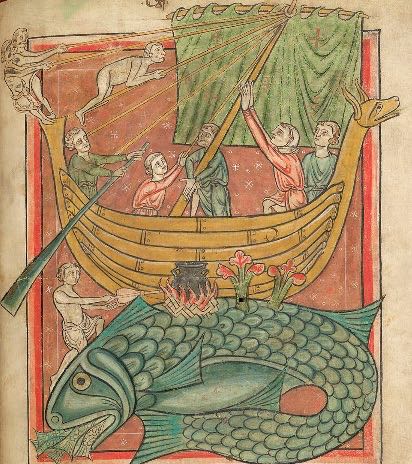

One of my favorite tales of pilgrimage is the Voyage of St. Brendan the Navigator. A tenth-century story about the life and travels of an Irish monk from the end of the sixth century, I first encountered this text at an early age, and was immediately taken with the image of a ship full of monks landing atop a whale. As I got older, I read the story again, and recognized it as an adventure story dressed as a saints’ life. As I have continued to live with it, though, I have come to the realization that there is more to it than that: it is a teaching about the life of prayer dressed as an adventure story dressed as a saints’ life.

Voyages and pilgrimages are a feature of early Irish monasticism. Modeled as it was on the lives and practices of the Desert Fathers and Mothers of Egypt, solitude and the waste places of the earth were important settings for monastic self-cultivation. We are told that Irish monks would climb into their flimsy coracles and push themselves off into the sea, trusting in God that they would arrive in some deserted place to dwell as hermits. Indeed, the Norse sagas tell of viking settlers landing in unknown terrain populated only by seals and the odd wild Irish monk.

These monastic voyages are inherently different from other kinds of pilgrimage; typically a pilgrimage is a journey to a destination and back again. The Irish trips tended to be one-way voyages into the unknown. Like Brendan, they set off in search of “the Promised Land of the Saints” guided only by the grace of God.

I can totally relate.

I often feel, like them, that life is sweeping me along to an unknown destination; that the waves and turbulence of life are threatening to swamp the delicate boat in which I ride. Juggling a relentless flood of calls upon my time and attention, I often feel like I’m just a few paddles away from complete shipwreck! And yet, as I sweep along, I have the sense I’m headed somewhere but the means of conveyance and direction of travel are not ultimately under my control.

The truth is that the monks were looking for a figurative location, not a literal one. When they went floating off in search of the “Promised Land of the Saints,” they weren’t expecting to land in a place flowing with milk and honey; they knew they would find themselves cast on some rocky shore to wrestle out the rest of their days, locked in combat with God and their own soul, warring against the passions, laboriously seeding the virtues in their habits, casting ceaseless prayers for the world and its inhabitants into the wind, and keeping watch for the incarnation of the Christ within their own hearts. This was the very opposite of escapism; alone, they had no distractions calling them away from relentless self-scrutiny and conversation with God. They were heading to a place of hard work to continue the voyage within their own souls towards the Triune God.

As I’ve learned more about the spirituality of the early monastic movements and the roots of the Desert encounter with God, the more depth I’ve found within the Voyage of St. Brendan. What I keep seeing now is that the voyage itself is a means for cultivating the destination. The habits of the voyage shape its end.

While the places that St. Brendan visits captivate the imagination, you’ll notice as you read that place has a very strong correlation with liturgical time. Brendan’s seven-year journey is a cycle, returning every year to the same locations for Maundy Thursday, Holy Saturday, the whole fifty days from Easter through Pentecost, and the Christmas season. Their wanderings amidst the wonders of the sea are liturgically structured.

Furthermore, Brendan and his monks discover not only new places and strange wonders, but new ways to pray: the Isle of the Birds and the Isle of the Strong Men in particular teach them specific patterns of prayer deeply rooted in the Liturgy of the Hours and the spirituality of the psalms that is its natural fruit.

Brendan’s journey is fraught with uncertainty and peril; he has only a vague sense of where he’s going and no idea how to get there. He has no preconceived notions of what he is going to encounter along the way, and finds everything from earthly gardens to the shores of hell itself. But what grounds him in the midst of these strange and magnificent sights is the rhythm and routine of the structured life of prayer. Steadily, over years, Brendan and his companions are transformed not just by the journey but by the practices of their journey—the repetition of prayer and praise. At their penultimate stop, they lay their eyes on a classical monastic ideal: a man whose practice of constant prayer has granted him the grace to live the life of an angel. Then, having seen this model of human life at the height of transformation, they at last walk the green and pleasant land of paradise itself.

As the seasons shift and the year turns its way towards Advent, Brendan’s voyage speaks to me of the importance of patterns, cycles, and rhythms. I’m not (thankfully!) drifting through the ocean in a coracle, but I am aware of the play of seasons and hours as I rush along in my courses. While I do not live the life of a monk, the same practices that sustained Brendan and his crew—the cycles of psalms, the rhythm of seasons—help orient me to my ultimate goal as well. As I pass through the wonders and oddities that characterize my own life, I too find it structured and supported by embracing the stability of the Church Year and the regular rhythms of the hours of prayer. In Morning and Evening Prayer, in Noon Prayer and Compline, the constant repetition of the psalms is an anchor despite the tumult around me. As I hurry my girls to school or ballet, I sometimes find the songs of the Isle of Birds (“Praise the Lord all his angels, praise him all his host”(Ps 148:2) and “Praise is due to you, O God, in Zion, and to you shall vows be performed” (Ps 65:1)) drifting through my head.

As we make our way into Advent, I invite you to take stock of your own voyage. What do you use as your own markers, your own practices of stability? How do you keep time along the way to lead you deeper into your journey into God? What are the practices that feed your soul, get stuck in your head, and recall you to the Gospel life?

2 comments

[…] Pilgrimage and St Brendan […]

Thank you. Just finished the Navigatio & pondering its relevance to my pilgrimage. Wonderful thoughts here!