Sometimes the thought of being a child again is appealing. Not so many worldly cares, decisions, responsibilities. A comfortable home provided for you. Time to run and play on the grass.

But many children do bear the weight of what is wrong in the world. Many children have not known the security of a warm home, their own bed, grass to play on, and a stable community in which to live and worship and learn.

This was true of the transient farm workers’ children I went to school with as a young child in the late 50s and early 60s during the few years my family lived in the agricultural valleys of Central California. One town where my preacher father was the pastor of a small church, we lived in a racially mixed neighborhood of lower-middle-class, stable families. My neighborhood playmate was a little black girl. I thought nothing of her color, except maybe fascination; and when we went into her house, I remember her mother as a smiling kind lady who offered me milk and cookies.

I was about 8 when culture shock hit. We moved to a small town in the San Joaquin Valley, where 2/3 of our elementary school were black and Hispanic, many of whom were transient farmworkers’ children. I probably stood with my mouth open the day I first heard the “N” word yelled at a group of kids and then the angry commotion that resulted. I had never seen or felt a group of people, let alone kids, that seemed to throb with such vehemence that day. A busload of children almost rocked with pent-up energy; arms and hands gestured out windows; heads yelled out slang and pejoratives to others on the sidewalk. During recess, gangs ran on the edges of the big playground, and often altercations exploded between groups. The teachers had their hands full trying to control the intensity in the classrooms.

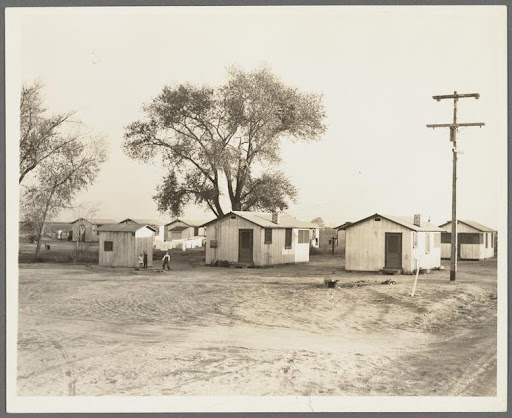

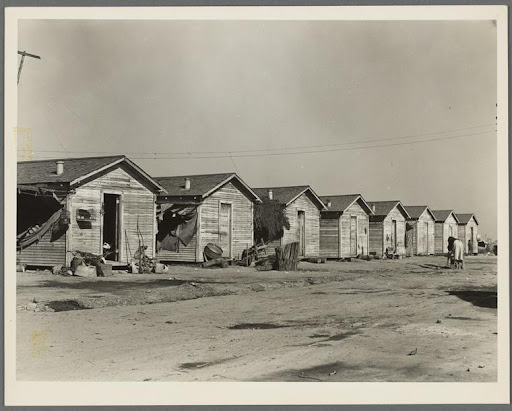

One day, Daddy drove my sister and me out to see a farm labor camp that a local farmer provided for his laborers and their families. I still remember our shock at seeing how some of our classmates lived. A semicircle of little shacks, some with cardboard patching up holes or windows. Old things sitting around. And everywhere just dirt. When it rained a big puddle formed. No grass to play on or trees to climb. No bushes or flowers anywhere. No bicycles or sidewalks to skate on.

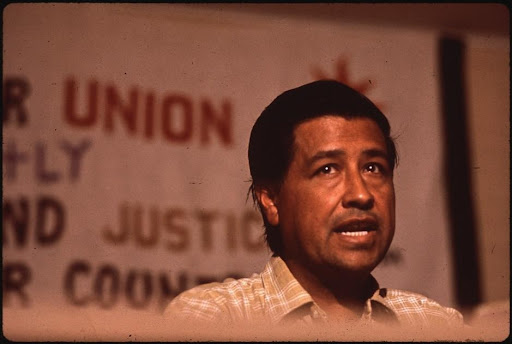

As children, my sister and I knew nothing of activists who were even then working to improve the living conditions and wages of farmworkers. But now I look back and realize the great work done by leaders such as Mexican-American labor leader and civil rights activist Cesar Chavez. I’m pretty sure some of the farmers in our church in those days weren’t happy that farm labor unions were forming, and that Chavez was organizing protests and negotiating for better contracts and laws.

Why is it that even Christian people often are slow to see such needs and embrace changes that are good for humanity? Yes, farmers were trying to make ends meet and realize a profit from their crops. Towns wanted order, not conflict. Schools wanted clean, healthy students sitting quietly at desks, ready to learn. And in the context of the Cold War, fears abounded that unions and other activist community organizations might be fronts for Marxist elements.

Life is messy. But society is only as stable and strong as its least powerful members. Cesar Chavez (1927-1993) knew this. Along with Dolores Huerta, he founded the National Farm Workers Association, which later merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee to become the United Farm Workers labor union. His politics combined with Roman Catholic social teachings. He was influenced by reading about the lives of St. Francis of Assisi and Mahatma Gandhi, and others to engage in nonviolent protest.

He organized workers, led protests, hunger strikes and fasts, and formed alliances. During his public fast in 1968, he received this telegram from Martin Luther King, Jr.:

You stand today as a living example of the Gandhian tradition with its great force for social progress and its healing spiritual powers. My colleagues and I commend you for your bravery, salute you for your indefatigable work against poverty and injustice, and pray for your health and your continuing service as one of the outstanding men of America.1

Through the many years of hard work and dedication of Chavez and others, the farm workers union became a political force whose support was sought by presidential candidate John F. Kennedy as well as California gubernatorial candidate Ronald Reagan. When Kennedy was assassinated, Chavez served as a pallbearer at his funeral. In the 1970s he met with Pope Paul VI, who commended his activism.

Chavez was (and remains) a controversial figure. But his lifelong, tireless work on behalf of unjust conditions for farmworkers, especially Chicanos in agricultural California, has had lasting good effect. His work continues to influence activists both in ecological ethics and in keeping the focus on human dignity—and, I would add, hope for the children.

In an open letter to the grape industry amid the Grape Strike, Chavez wrote:

The men and women who have suffered and endured much and not only because of our abject poverty but because we have been kept poor. The color of our skins, the languages of our cultural and native origins, the lack of formal education, the exclusion from the democratic process, the numbers of our slain in recent wars — all these burdens generation after generation have sought to demoralize us, to break our human spirit. But God knows we are not beasts of burden, we are not agricultural implements or rented slaves, we are men. And mark this well [..] we are men locked in a death struggle against man’s inhumanity to man in the industry you represent. And this struggle itself gives meaning to our life and ennobles our dying.2

__________________________

Notes: 1 & 2 Accessed at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cesar_Chavez

Photo Credits:

- Charles L. Todd and Robert Sonkin migrant workers collection (AFC 1985/001), American Folklife Center, Library of Congress

- National Farm Workers Association protest buttons, Creative Commons

- CAESAR CHAVEZ, MIGRANT WORKERS UNION LEADER in 1972, public domain

- An example of housing for farmworkers and families in mid-20th century in California, public domain

Lent continues, the season is still full of possibility and promise. Are you finding ashes and desiring beauty? Now available as an online course, this virtual retreat will help you to lay out your garment of lament and put on your garment of praise. Gather your joys and release your grief with Christine Sine and Lilly Lewin! Click here for more info!

Lent continues, the season is still full of possibility and promise. Are you finding ashes and desiring beauty? Now available as an online course, this virtual retreat will help you to lay out your garment of lament and put on your garment of praise. Gather your joys and release your grief with Christine Sine and Lilly Lewin! Click here for more info!