Many years ago I found myself in a really hard period of time in which I almost lost my life on several occasions; both through the disease I had, and at my own hand. The pain I feel as I look back on that period of life and the utter despair I felt have diminished over time, but it certainly opened my eyes to see more clearly what other people are going through.

Most importantly I see it was in that time God stopped me: Stopped me from self-destructing. Stopped me from continuing in the hectic pace I was on. Stopped me for long enough to grab my attention and teach me to listen.

What do you say to God when there is nothing but anger wanting to escape your mouth? When all you have to say is so incredibly horrible that you are shocked at the depth of anger held in your heart? You let it out. You speak to God and be real about how you feel… and when you reach that time you think you have spoken, ranted, raged it all out, you cry… and eventually you listen.

A heart exposed to your creator will find it is secure in those love filled hands and heart, when eventually you stop. And listen. And you’ll find the whispers of the one who knows you even more than you know yourself. That whisper becomes louder, and more clear… and the clarity of the words being spoken to you… over you… come like the roar of a lion, or like a voice in the wind.

Listen to those wind words….

What wonderment do you have in store today God?

What whisper comes on the wind?

What light will raise my spirit, as a gentle breeze wavers in?

Wet leaves glisten in sunlight as branch sway in a dance,

And I sit in the quiet with eyes open…

What wonderment do you have in store today God?

What word comes on the wind?

As birds sing and call both melody and harmony

A page turns; a new chapter? Or perhaps a new moment?

As my heart beats, and I sit in the quiet with ears open…

What wonderment do you have in store today God?

Will I hear your whisper on the wind?

As I sit in my tiredness, will I sleep through this day?

Maybe sing with bird’s melody, or dance with frivolity?

As I sit in the quiet with mind open…

What wonderment do you have in store today God?

Will you speak on the wind? Or is this a day of silence?

Will I bask in your sunshine? Settle from my spin?

Will I hear your voice today?

As I sit in the quiet with heart open…

As I sit and wait, open to you Lord, will you come as the wind?

A rushing, cleansing Zephyr? Or a rustling enfolding Breeze?

Will you sweep in like a storm? Or spring up gently to caress my face?

What wonderment do you have in store today God?

I wrote this poem about 10 years ago, as I found that God did indeed speak to us if we are willing to quiet ourselves and listen.

If I take nothing else from that horrendous time away with me, the recognition that God will whisper to and (when necessary) roar at us has to be a great lesson.

So where are you up to today? Do you hear that quiet whisper inviting you to journey deeper? Move forward? Do this? Stop that? Is it an invitation to slow down and hear the God of the universe sing a song of deep love for you? Or maybe it’s a song of healing for old or fresh wounds? It takes a step on your part… invite God and listen.

Today I finish with a prayer… if you will, make it yours…

Oh God! Take me to that place where your beating heart sings in my ear. Take me to that place where warmth enfolds me, where grace will hold me. Take me to that place where my Saviour whispers, and truth breaks down the strongest of my defenses…. In the name of Christ I pray.

Today’s post is part of our series on listening.

As I write this I am standing, not sitting. Six days past, working in the garden, I pulled a lower back muscle and have found myself confined to the bed and couch. I cannot sit down without pain. There is slow and consistent recovery, aided by a great physio and lots of love from friends and family, but not having the internet on my phone or not owning a laptop, I have missed so much sitting at the computer connecting with my Christian writer friends, being blessed and fed by quotes, articles, and devotionals to which I subscribe.

The day before my back injury God spoke so clearly verse after verse in my bible about lifting the burdens from my back. When I then injured it so badly, I struggled to make sense of what I had thought I had heard, and understood, and claimed as a promise of healing and restoration. Perhaps I simply hurt my back because I went outside and gardened in the cold of the early morning, when my body was cold (most likely), perhaps I needed a good break and to slow down and come away for a while; and yet perhaps I had reached a point where I was weighed down with so much, that in his wisdom and love he was pointing out to me that if we are not careful our burdens become so heavy, they break our backs.

Listening to God, sometimes I feel I hear him so clearly, and other times I don’t know if what we hear is our own voices or his; often I think he has to break through the din caused by our own fears, anxiety, guilt. Sometimes I want to provide an explanation to what may be beyond explanation, or beyond the need for me to understand; and the ‘reason’ that I give for things is often mine, not his. Although I have rested in his presence this last week, he has been quieter than I felt he was before the injury. Maybe times of brokenness and healing towards restoration are times of silent reconstruction. Just as the deep injured muscles in my back slowly restore, the healing work in my heart and mind is tended to by him with the same silent, tender, but thorough care.

If there is one word I have heard this past week, it is ‘wait’

To this end, I found and re-read the old poem below which I wrote once for a friend who was at crossroads in his life.

We lie in wait, trusting in him, knowing his ways are not our ways, his thoughts not ours, but his purposes – always for our good.

We wait,

We wait for the evening’s respite, for the week’s end, for the Spring

to come, again.

We wait for the weather to clear, for the sun to shine, for the days

to lengthen.We wait to take a break, we wait for opportunity, we wait for time

to do, all we’ve been planning.

We wait for blossoms to bud on the burgeoning wood, for the leaves

to green, and the bird’s dawn chorus.We wait for health, and wholeness, for full healing to come and

revive our spirits.

We wait for inspiration and words of discernment, and a sense of God’s

clear calling.We wait because we know

There’s better around the corner. That love grows,

and time heals, and joy comes in the morning.

Which is true, but it is also true too, that God, our God

waits with patience, ‘to be gracious to us’ too.He waits,

While we wait for the tide to turn, and the river to subside,

and the leaves to change.

He waits at the river ford where we make our own way,

challenges the stepping stones.He waits while He has us, moulding to His hand’s shape,

in the heat of His kiln.

He waits while we thirst in the wilderness, patience

doing its perfect work.He waits for our yearning to cease, and for us to recognise

the blessing in every heartbeat.

As the acorn is split open, in the moment life is found.

Not ahead and not behind.So He waits,

While we wait for Summer to come, for seasons to change,

and His favour to return.

He would that we would hear Him calling in the moments we discard,

wring out life for all its worth.As He waits in the here and now.

Ana Lisa de Jong

Living Tree Poetry

“Yet the Lord longs to be gracious to you; therefore he will rise up to show you compassion.

For the Lord is a God of justice. Blessed are all who wait for him!”

Isaiah 13:18 (NIV)

Today’s post is part of our series on listening.

By Andy Wade –

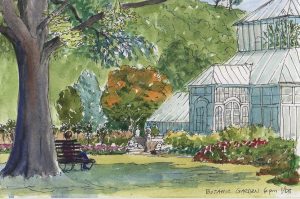

The backyard is really a living metaphor for life.

A quick look yields some obvious points:

- You reap what you sow… most of the time.

- Some things simply can’t be rushed.

- Planning and preparation yield the greatest results.

- There will always be pests.

- Many of the things you thought were pests actually have an important role to play – they just need to be better understood.

- There will also be “beneficials”, those that join you in the process of bearing fruit.

Spending a bit more time exploring, one discovers a deeper level of truth:

- Planting all the same crop in one space increases the chances of problems, while diversity yields mutually beneficial results.

- My garden is not just for me, it’s a celebration of life and beauty that can be shared with neighbors, friends, family, and even strangers. In this way, the garden becomes a source of celebration, joy, and community.

- You always have a choice how to deal with problems – there are toxic methods that simply attack, and there are gentler, less destructive approaches.

Stepping deeper into the backyard reveals even more:

- There is way more going on here than meets the eye!

- The less you disturb the soil, the more time you’ll have to enjoy and celebrate the harvest.

- The garden system, like all of creation, has ways to repair itself. I don’t have to spend so much time “fixing things” if I listen and learn from God’s creation.

Now here’s an interesting exercise. Go through the above lists slowly and think more specifically:

- How do these ideas apply to my family?

- How do these ideas apply to my neighborhood?

- How do these ideas apply to my church community?

- How do these ideas apply to my city or town?

I did, and the insights were amazing!

by Gil George

In a recent blog post (Dear God Time) I shared our family bedtime ritual. The key pieces of our bedtime prayers are in asking my kids who they want to thank God for, who they want to pray for, and what part of the beautiful creation they are thankful for or want to pray for. This has become a time of holy listening for me as I get to hear my daughters’ perspective on what is important, who really needs prayer, and to hear their words of faith and wonder.

One key practice in listening well to their faith is not to put words in their mouths, but to allow them to direct these pieces of prayer. By asking them to initiate I get to hear who the really special people are. My girls have a very short list of people who they are especially thankful to God for, and I have not yet made their list. What I have found is that they list off the people who have gone out of their way to build connection, not the default family members, but the people from outside who have especially invested time and love into them. I have learned through listening to my girls who the treasures are in their lives, the surrogate aunts and grandparents and surrogate grandparents who they know love them. I have come to treasure these friends above and beyond because they love above and beyond.

My girls’ “pray for” list is equally illuminating to me. I get to hear about the bullies and the bullied, the pieces of hurt that I miss, but my kids see. I hear them pray for friends that have moved away, old church folks from my previous call, and I get this incredible window into the compassionate heart of my children. By listening to their compassion I have learned who I might have missed, and how often I miss. I also get to hear them wrestle with things they have heard about that they don’t quite grasp and are confused about in others and by listening to their confusion I can begin to wrestle with my own. Given free rein to bring anything or anyone to God, my girls do, and I have learned a lot about the childlike faith of lament and bringing “owies” to be kissed by the presence of God.

The last piece of listening really taps into childlike wonder at things we adults stopped noticing a long time ago. During our prayers for the beautiful world there was a six month period of time in which one of my girls was thankful for the clouds that give us rain, snow, sleet, hail, and shade from the sun. For how the clouds turn pretty colors and make fun shapes. Six months of wonder at something I occasionally swear at. What a perspective shift it is to be given the gift of listening to wonder and awe. Over time there were thanks for dogs, mountains, waterfalls, dogs, forests, sheesh dad take a hint dogs, beaches, and any body of water larger than 3 inches. We tapped into that wonder when at her first time to the ocean our youngest looked out with wide eyes and shouted “Puddle!” and prayed for that huge “puddle” for weeks.

I have found that listening to the prayers of my children has opened my eyes to a joyous wonder in being a child in God’s loving arms. Sometimes I even get to model that love, but most awesomely, I get to rest in that love as I listen to the prayers of my children.

Today’s post is part of our series on listening.

by Lynne Baab

by Lynne Baab

Some of the same obstacles that make it challenging to listen to people also make it hard to listen to God. I learned this insight a few years ago when I did some research about listening.

I interviewed 63 ministers and congregational leaders in the US and the UK about listening. In my interviews, I asked about listening within congregations, listening to the wider community, listening to God and obstacles to listening. I heard lots of great stories (and the stories shaped my book, The Power of Listening, reviewed here on Godspace.) I was quite surprised that most of my interviewees became most animated when they talked about obstacles to listening.

They talked about challenges to listening that come from external sources: noisy rooms and people who talk too fast or too softly. Several interviewees said that they knew individuals who had never been listened to, so they had no models for how to listen well. These obstacles relate to listening to God just as much as listening to people. What’s the equivalent of noisy rooms and voices that are hard to hear when we think about listening to God? Too much activity, bustle and noise – these definitely impede our ability to hear God. Christians can also lack models for listening to God because it seems like a weird or unconventional activity.

My interviewees also talked a lot about obstacles to listening that come from within. I want to lay out three of the inner obstacles they talked about and show how those obstacles relate to listening to God as well as listening to people:

1. Preoccupation with the to-do list or what’s next on the schedule. Our swirling thoughts about activities and what we have to do next can keep us from slowing down to pay attention to the person in front of us, and they also prevent us from paying attention to God’s still small voice.

2. Concern about what we’re going to say next or that we will be required to do something we don’t want to do in response to what we’re hearing. Our uneasiness about we will need to do next impedes listening to people. Will we be able to respond appropriately to what we’re hearing, whether that’s the words we say next or the action we might be required to take? This same kind of fear blocks our ability to hear God. Will God demand of me something I don’t want to do?

3. Fear of silence. Quite a few of my interviewees said that so many people are afraid of silence, or are at the least quite uncomfortable with it. We have habituated ourselves into a constant stream of noise: music, videos, TV, movies, video games, etc. Smart phones enable us to avoid silence entirely if we want to. Silence when talking with others is essential from time to time in order to let people reflect and dig deep into their thoughts. Many people feel very uneasy if silence falls in conversations, so they rush to fill the silent space with words. If we are used to filling silence in conversations with words, we are likely to do the same in prayer.

My interviewees mentioned other inner obstacles as well. Overcoming these obstacles, both in conversations with people and with God, requires self-awareness and intentionality. “Be still and know that I am God,” the psalmist recommends (Psalm 46:10). Being still requires a desire to do so, as well as lots of practice. It doesn’t feel natural at first. This blog gives many practical ideas about how to learn to be still and listen to God.

Here’s my practical idea: I want to encourage you to think about your biggest obstacles to listening to people, and then reflect on the ways those same obstacles influence your ability to listen to God.

Today’s post is part of our series on listening.

by Christine Sine.

I am in a season of what I think of as holy waiting. I am sitting in that time between now and not yet where I am very aware of what is behind me but not sure of what lies ahead. It is holy because I sense it is both God ordained and God directed.

Holy waiting is active waiting, not sitting around hoping God will do something new but actively moving towards the new and listening to God and to others about how that new should be shaped. It is the kind of waiting we need to embrace whenever we are unsure of the path ahead.

Listening in Community

Holy waiting begins with listening. We listen to God. We listen to our own inner promptings and we listen to the wisdom of community. At least we should. Community listening and group discernment, like the Quaker discernment process we adopted in MSA many years ago, are often the most neglected aspect of listening in times of transition and change. Yet in many ways these are the most important. None of us hear the voice of God clearly 100% of the time. Our cultures, our world views, our leadership styles all get in the way. Friends, colleagues and consultants provide the checks and balances we need to keep us on track,

Listening in community often seems to slow a process down. We want to hurry along and reach the destination but healthy waiting takes time. As we mentioned in our Friday post The Complexity of Transition our listening process for my current transition began several years ago. It has involved many people both within and outside the MSA community. At times it seemed to drag. At times it seemed to grind to a halt. Yet in the background God was always at work, helping us ask the right questions and reach for the right solutions. Without community involvement we may have moved faster but I suspect we would have made more mistakes.

Listening in Repentance and Forgiveness.

One of the hardest questions I have had to ask myself as I prepare to hand over my leadership role is What should I have done differently? It is not an easy question to ask and an even harder one to answer honestly both to myself and to others. To face with honesty and vulnerability the mistakes I have made and the wrong steps I have taken is an important step on the path towards wholeness. Seeking forgiveness from those who may have been hurt in the process is even more important. It frees me up to move forward and it also gives freedom to those who follow me to not be weighed down by the baggage I might leave behind.

Listening through Prayer

This probably seems like the most obvious way to spend our time in a season of holy waiting. Yet often we pray in all the wrong ways. Our prayers are more demands for certain answers than prayers for God’s wisdom and direction. Prayer during a time of holy waiting should be more about active listening than talking, more about looking for the right questions than seeking the right answers. Keep a journal. Write down the questions that come to mind and the and answers you sense God is giving you.

Listening through Serving.

Holy waiting is a time for reaching out to others. How can we serve our neighbours, our colleagues and those around us as we would like to be served? Serving others helps us get our own lives in perspective and not think more highly of ourselves than we should. It liberates us from the need to be in control, often opens our eyes to new ways of thinking and makes us aware of new possibilities that God wants us to imagine.

Jesus constantly gave up power he did not grasp for it. He refused to allow his followers to make him into the kind of leaders the Jews and Romans specialized in where authority was used to control and often to subjugate others. Jesus leadership model was that of true servanthood. Through word and example he embodied a different model of leadership. He rarely told his followers how to do something he asked questions that enabled his disciples to find the answers that God had already placed within their hearts. Serving others helps us to grow into this type of leadership model.

Listening by Striving for Justice

Times of waiting often bring awareness of injustice in our own lives and in the lives of those around us. Sometimes situations that have been festering quietly in the background suddenly spring into life. Waiting clarifies truth. God nudges us to see how we have treated others unjustly, or how we have been treated unjustly and need to speak out. Listening to the still small voices that help us make equitable and just decisions is much easier in times of holy waiting.

Listening through Resting.

Can rest be active you might ask? The answer is yes. Holy waiting means learning to rest in each moment, to savour its beauty and connect to the God who is present in that moment in unique and special ways. This takes intentionality and purpose.Learning to not strive for future success or accomplishment is very countercultural and often seems counterintuitive. As I have mentioned before, our natural tendency is to be non reflective, rushing through life with blinkers on. To change that is an act of the will that does not come easily to us. Yet the rewards are enormous.

What is Your Response?

Sit quietly, take some deep breathes in and out. Consider the places in your life where you feel you are in a process of holy waiting. Or perhaps you are not in a time of holy waiting, but are aware that God wants you to listen in new ways. Watch the video below. Which of the suggestions above most resonates with you as a means of response? What else is God prompting you to do?

Today’s post was inspired by this sermon given by Susan Chloupek at Saint Andrews Episcopal Church in Seattle.

This month I am reading Keith Anderson’s book ‘A Spirituality of Listening: living what we hear’ and I am reminded that the world is simultaneously much bigger and much smaller than I realise. In the midst of a dense period of brain fog, migraine and depression, it has been good to be challenged to keep looking up from bed to hear the wild wind rustle of God’s Grandeur out of the window and to be confirmed that the path I have chosen, to see God in the tiniest details of my small life, is indeed a fruitful way forward. The gold thread twisting through Anderson’s book is that ‘God speaks in ordinary things often silenced because we forget to listen’ (60) and that ‘our work done in the most ordinary ways becomes extraordinary if we remember one thing: the most ordinary things are transformed by the possibility of God’s presence’ (61). His conviction is that ‘wisdom still cries out if we can learn how and where to listen’ (24).

Nearly four years ago I started writing about the intersection between contemplative spirituality and photography on a blog called shot at ten paces. The name emerged out of a conversation with the poet Gillian Wallace about my frustrations with my photography. I characterized my seeming inability to learn and retain the most basic technical knowledge, which would develop my photography skills to commercial levels, as an inability to ‘see the big picture’. All I did was take photographs of was what was in front of me at home, or of what I could see from my wheelchair, my front doorstep, or out of a car window. My photos reflected my mental and emotional state – I needed to find my God in my here and my now, because God felt a long way distant.

But the presence of rain drops held inside a net of lobelia on the edge of a hanging basket, or the colour of a pot on a windowsill, or the weeds thrusting up through the concrete path, all began to catch at my notice and I explored them in countless close ups with camera in hand. Yet it was only during this conversation with Gillian that I discerned that this way of seeing really was what I was interested in. Far from it being a limited way of seeing imposed by physical and mental illness, it was a freeing gift that I was naturally attracted to. I had been given the opportunity to see what others often overlooked, and by being open to receive images through a camera, I had the opportunity to become a co-creator with God.

Since that conversation I have become passionate about communicating, like Anderson, that ‘there is an invitation to an orientation of one’s life to a universe that is alive with presence and voice, always with “more that can be told”’ 14). So with camera in hand, (a DSLR when I am well enough to hold it, an iPhone on a more daily basis) I explore my faith conviction that God is in the small things, God is in the details. And so, to use Lucy Ellman Clark’s phrase I am on a ‘Pilgrimage of the Quotidian’. God asks me to pay attention, to be present to God’s presence, which will always be right in front of me, if I have the eyes to see and the ears to hear.

As Keith Anderson affirms, such exploration requires a ‘posture of expectancy’ (39). I need to get curious about what God is doing, what God is saying, where God is living in whatever this day brings. My approach needs to be one of wonder, although as soon as I write that word I am reminded how far short I fall of living with such imaginative openness in most moments of my life. Yet I know that we are all beginners in this way of listening. I can begin again an intentional practice to have a conversation with God which begins with my receptivity, not my words; and rest safe in the knowledge God’s presence can pierce the blanked blockedness of an exhausted mind.

It seems no coincidence that as I read Keith Anderson’s encouragement to cultivate ways of listening for God’s presence in the ordinary tasks that face me this day, I stumbled over this:

Wisdom is

so kind and wise

that wherever you may look

you can learn something

about God.

Why

would not

the omnipresent

teach that

way?

St Catherine of Siena/ Daniel Ladinsky

Kate Kennington Steer is a writer and photographer with a deep abiding passion for contemplative photography and spirituality. She writes about these things on her Shot at Ten Paces blog. She has recently begun an offshoot project, posting a daily iPhone image as a ‘act of daily seeing’ on Facebook. Join in with gentle ambling conversations about contemplative photography by visiting Act of Daily Seeing.

All the above images are iPhone images.

As an Amazon Associate, I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links.

Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

When referencing or quoting Godspace Light, please be sure to include the Author (Christine Sine unless otherwise noted), the Title of the article or resource, the Source link where appropriate, and ©Godspacelight.com. Thank you!