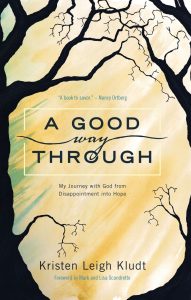

Kristen Kludt —

Excerpt from her new book, A Good Way Through. Available now!

In my experience of Los Angeles, everyone who lives there, regardless of years, seems young. You have to be resilient, creative, and perhaps just a little bit self-focused to survive there. On my first day of teaching, just after we had moved to LA, I noticed trucks unloading equipment in the school soccer field. “What is that?” I asked a colleague.

“The industry,” she said, as if that explained everything. In time, I would discover it did. “The industry” in Los Angeles is the entertainment industry, and much of the life of the city revolves around it. The culture is fast-paced, even cutthroat. People hoping to “make it” in LA save up all the money they can, and land there ready to work around the clock to succeed. They sacrifice sleep, comfort, even friendships to try to live into their calling. A few succeed overnight. The rest doggedly keep at it, get day jobs or head “back East” to save up more money and try again.

Our life in Los Angeles was rich, but it lacked perspective. Most of the people we knew were under forty. So, when my therapist introduced me to Sister Margaret, my hopes were high for a deep connection with someone who had the perspective of a lot of life behind her.

I drove the thirty miles to my first meeting with Sister Margaret, arrived twenty minutes early, and parked across the street, using those minutes to quiet my rapidly beating heart. I was nervous about meeting this woman; I wanted her to like me. I crossed the street to the Villa, and Sister Margaret greeted me on the concrete walkway beneath towering evergreens. “I am so glad to meet you.” She opened her arms wide to usher me inside.

Sister Margaret is small, humble, unassuming, and filled to the brim with quiet delight. When we met, she had been a nun for sixty-five years. We sat opposite each other in comfortable chairs in front of an empty hearth. Through the window I could see the bright green and red leaves of a poinsettia, and through that, the green grass. Sister Margaret asked me to light a candle, and we prayed.

In that season I was impatient with my own lack of transformation. I could see signs of growth: I felt safer in the darkness and I experienced more love and joy than I had in prior months, but I was still struggling. Can’t I just fix this and move on? I wondered. What else do I need to do to heal and change more quickly? I interrogated myself daily.

As my impatience became apparent in our conversation about life and faith, Sister Margaret said something to me that I have found myself saying to other people, and to myself, many times in the years since: “This earth is very old, and our God is very patient. God is a gardener. Gardeners don’t go around kicking the cabbages and telling them to grow faster.”

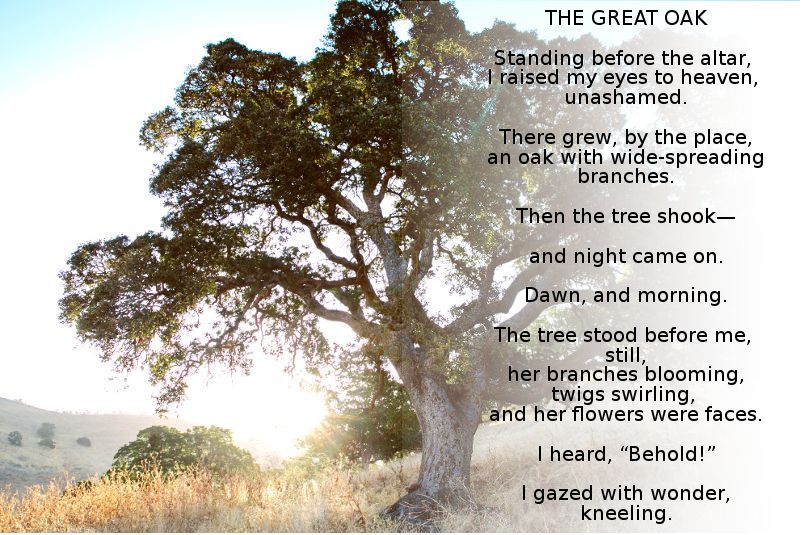

When I closed my eyes to pray with her that morning, I saw in my mind a great tree, and I thought of this great, old earth. The tree in my mind was tall like a mountain and dressed in a pattern of green boughs. It was quite still, but I knew, beyond my ability to perceive, it was stretching ever taller with the turning of the earth.

A few weeks later, at a Kairos worship gathering, one of our pastors spoke about being oaks of righteousness. Afterward, as we sang, I again closed my eyes, and a prayer settled on my shoulders like a shawl: God, grant me the faith of an acorn.

Small enough to nestle in the palm of my hand, acorns grow into trees large enough to shelter a family from sun or storm. From what we know of them, they do so without planning or effort on their own part. They don’t have to will themselves to grow faster. They are subject to the wind and the rain and the soil and the sun and they will grow, quickly or slowly. They submit themselves to burial beneath the soil, to the breaking of their skin and their hearts, and so begin their lives as trees.

Years turn to decades, and they grow taller, soaking up only what comes to them—there is no thought of running after what they need for growth, only a slow, upward journey toward the light. As they grow taller, so they grow deeper, roots digging ever more surely into the soil that will offer everything they need to live, or won’t, and that will be the end and they will break and fall and rot and become new life and sing new songs as insects and grubs and salamanders.

The next time I visited Sister Margaret, I told her of my acorn prayer. She smiled her sweet smile, and said, “Come.” She led me out of the house, down through the garden, and around a corner to a nook under the evergreens. “Look,” she said. “I brought this home as an acorn. I didn’t think it would grow, but I planted it anyway, and look!” In a large pot was a miniature oak. Only three feet in height, it had the gnarled, scrappy look of the black oaks of Yosemite. It had few leaves, and fewer branches, but it was a living, breathing tree before us. “Someday, it will outgrow its pot,” she said, “and then I will plant it in the ground.”

I drove home under the bright blue sky. I wondered, what does it look like to grow like an oak? To let go of responsibility for my own transformation and just to allow myself to be loved? I didn’t know yet, but I would continue to make space in my life for this God I wanted so desperately to know. I prayed, God, grant me the faith of an acorn, that I might find life in death and trust that I will grow, like a river awash with rain, without striving.

A Good Way Through: Vignettes from Kristen Kludt on Vimeo.

Kristen Leigh Kludt is a contemplative Christian writer and spiritual guide. Mother to two boys, she lives, works, and plays in San Francisco’s East

Kristen Leigh Kludt is a contemplative Christian writer and spiritual guide. Mother to two boys, she lives, works, and plays in San Francisco’s East  Bay, where her husband is a pastor. She is growing daily toward a life of integrity and love.

Bay, where her husband is a pastor. She is growing daily toward a life of integrity and love.

Excerpt from A Good Way Through: My Journey with God from Disappointment into Hope (February 21, 2016)

Titles have never been my strong suit.

I used to write regularly for a Christian newspaper, and no matter how hard I worked on the titles for my articles, they would inevitably be changed in the editing process. Today when I write a sermon, the title often comes to me last, only after the sermon is finished. Even as I write this article, I’m saving the title until the end.

So when Abingdon Press invited me to write a Lenten Bible study for 2017, I didn’t mind at all that the title had already been chosen. To follow up their previous Advent study called God Is With Us, the editor had chosen Christ Is for Us for Lent. The two titles worked together beautifully—the God who is with us during Advent and Christmas would become the Christ who is for us during Lent and Easter.

So when Abingdon Press invited me to write a Lenten Bible study for 2017, I didn’t mind at all that the title had already been chosen. To follow up their previous Advent study called God Is With Us, the editor had chosen Christ Is for Us for Lent. The two titles worked together beautifully—the God who is with us during Advent and Christmas would become the Christ who is for us during Lent and Easter.

For the next months, as I lived with the Revised Common Lectionary texts for the Lenten season, I continued to deepen my understanding and experience of Christ is for us. When Jesus spoke to the Samaritan woman at the well with respect (John 4:5-42), when he gave sight to the man who had been born blind (John 9:1-41), when he raised Lazarus from the dead (John 11:1-45), he showed that he was on their side. The presence of deep social division, disability, and even death did not prevent him from reaching out, coming alongside, and transforming their lives

Today we also face deep social divisions–a host of “isms” around the world and between people who live in the same country and city, and sometimes even on the same street and within the same church or family. We also struggle with various disabilities—both physical disabilities like the blindness of the man who received his sight and the spiritual blindness of some of the Pharisees. Like Lazarus and his family, we also face illness, death, and mourning, and Jesus comes alongside us with tears, words of comfort, and the promise of new life.

Today we also face deep social divisions–a host of “isms” around the world and between people who live in the same country and city, and sometimes even on the same street and within the same church or family. We also struggle with various disabilities—both physical disabilities like the blindness of the man who received his sight and the spiritual blindness of some of the Pharisees. Like Lazarus and his family, we also face illness, death, and mourning, and Jesus comes alongside us with tears, words of comfort, and the promise of new life.

Christ is for us—what a beautiful message for the coming Lenten season. As we reflect on Jesus’ journey to the cross, as we think on his suffering and death, we can be assured that Christ is for us. Whether we plan to give something up in memory of his suffering, or take on something new in anticipation of the resurrection, we do not do these things to win God’s approval. Christ is already on our side.

What’s more, this message is not only for Lent. While the Revised Common Lectionary designates certain texts for certain seasons, Scripture speaks across the seasons and to all of life. So yes, Christ is for us during Lent, and yes, Christ is for us at all times. We are not alone. We can rest in God’s presence and healing, knowing that the Spirit is at work all year round.

April Yamasaki serves as the lead pastor of a mid-size, multi-staff church, and is the author of Christ Is for Us, Sacred Pauses, and other books on Christian living. She blogs regularly on Writing and Other Acts of Faith and When You Work for the Church. Christ Is for Us: A Lenten Study Based on the Revised Common Lectionary is available from your favorite bookstore and in paperback, large-print, and e-book formats from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Cokesbury.

April Yamasaki serves as the lead pastor of a mid-size, multi-staff church, and is the author of Christ Is for Us, Sacred Pauses, and other books on Christian living. She blogs regularly on Writing and Other Acts of Faith and When You Work for the Church. Christ Is for Us: A Lenten Study Based on the Revised Common Lectionary is available from your favorite bookstore and in paperback, large-print, and e-book formats from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Cokesbury.

by Christine Sine.

As many of you know I am working on a new book on creative spirituality. I have recruited a group of friends to walk with me through this process and add their own creative energy to the project. Last week I sent some beginning ideas to these friends and received this wonderful response from Kim Balke who is an expressive arts therapist in Canada.

From my point of view as one who works with children most of the time, I wanted to add a suggested exercise to help free your soul based on Jesus’ words, “Unless we become as children we cannot enter the kingdom of God “(the most creative dimension I know of!).

Here it is: take some time to enjoy a few picture books for children, some from your earliest childhood memories, some contemporary. They may help foster a heart posture of openness, curiosity and wonder. Here are a few I recommend and that I have in my tool box with children (and really enjoy myself), and I have these so I can lend them to you when you come up this way, too. You could probably get most of them in the public library, I think:

Visiting Feelings, by Lauren Rubenstein

I Dreamt, A book about Hope, by Gabriela Olmos

Maybe Something Beautiful: How Art Transformed A neighborhood, by F. Isabel Campoy

The Night Gardener, by The Fan Brothers

Daniel Finds a Poem, by Micha Archer

What Do you do with an Idea? by Kobi Yamada

Always Remember, by Cece Meng (about grief,loss)

After reading a story, respond with a doodle, drawing, poem or even keep a few rhythm instruments handy and discover the sounds that hold something that stood out for you in the story…a page of illustration you are drawn to, perhaps.

Her idea really resonated with me as I prepare for Lent. While we were in Australia I purchased a very special book from my childhood called The Magic Pudding. It was created almost 100 years ago by Norman Lindsay an amazingly creative artist, sculptor and writer. It has wonderful illustrations in it, but to be honest I hardly looked at them. After all I am no longer a child. My adult self valued the book rather than the story.

Kim’s suggestion gave me permission to unleash my inner child, take out the book and enjoy the innovative depiction of Australian animals. Their creation stirred the imaginations of many Australian kids and certainly stirred mine again as I reflected on them.

A couple of days ago I was given another wonderfully enriching children’s book The Harmony Tree by Randy Woodley. This time I needed no prompting to explore and reflect on the beautiful illustrations and story. My inner child responded immediately stirring new places of creativity and imagination within my soul.

Imagination and creativity is at the heart of who God is and who God has created us to be. Returning to that imaginative framework of childhood is one important way to tap into it. So maybe this Lent what we need to let go of is the constrictive and unimaginative views of adulthood and return to the creativity of childhood.

A couple of years ago I wrote several posts about needing to rediscover the creativity of childhood that I thought you might want to revisit as you think about this: Get Creative and Play Games for Lent and 5 Ways to Foster Creativity in Kids During Lent.

What is Your Response?

When was the last time you looked through a children’s book, not to read it to a child but for your own enjoyment? When was the last time you allowed your inner child to emerge?

Grab a children’s book – your child’s, your grandchild’s or one you still have that you treasure from your own childhood. Look at the illustrations. What thoughts are stirred? What images come to mind? What creativity does it ignite within you? Go through the exercise Kim suggests and respond with a doodle, drawing, poem or even keep a few rhythm instruments handy and discover the sounds that hold something that stood out for you in the story.

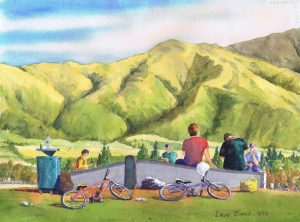

Twenty-five years ago, my congregation began offering contemplative prayer events, sometimes in a class setting on Sunday mornings and sometimes at quiet day retreats on Saturdays. I went along to try out silent prayer with others. I learned how to do centering prayer and the prayer of examen, as well as lectio divina . I took to contemplative prayer like a duck to water.

I realize others don’t always have the same experience that I did, but for me, contemplative prayer was like coming home. In the midst of the verbally oriented faith that I experienced at church and in smaller gatherings, contemplative prayer gave a sense of God as big and wild and wonderful—the mystery beyond our comprehension, and yet also our refuge and fortress, a source of peace, comfort and security.

I needed that sense of peace. My life in those years was tumultuous and stressful. My husband was deeply unhappy at his work. Our kids had entered adolescence, and we were baffled and frustrated by their increasingly challenging behavior. I had finished a seminary degree and was a candidate for ordination as a Presbyterian minister, but I had no idea when or if I would ever be ordained, or even if I really wanted to be.

I felt called to congregational ministry, but I was doing some part-time writing and editing for the Presbytery and Synod, and writing was becoming an increasingly significant part of my life. I was worried about my future. Would it include church ministry or writing? How would I decide?

I came to contemplative prayer and found relief from the turmoil and a glimpse of “the peace of God that surpasses all understanding” (Philippians 4:7). I enjoyed the sense of personal peace that came from contemplative prayer for several years before I had a major aha moment. This burst of insight came from an article in the journal Weavings entitled “Prayer as Availability to God” (Sept/Oct 1997).

The author, Robert Mulholland, points out if contemplative prayer involves listening to God, then we will become more attuned to God’s purposes and goals if we engage in contemplative prayer. If contemplative prayer includes offering ourselves to God, then the more we pray in this way, the more we will be able to participate in God’s purposes and goals. In other words, we will become more available to God.

Until I read the article by Robert Mulholland, I hadn’t realized that contemplative prayer was playing a role in tuning my heart to God’s values and empowering me to serve God more fully. The more I reflected on my experience with contemplative prayer, I realized that along with the peace, I was indeed sensing God’s guidance more clearly and growing in my ability to follow God’s leading.

Contemplative prayer, then, is not just a nice thing to do that helps us find relief from the pain of daily life. It does do that, but the peace God gives through contemplative prayer enables us to look beyond our own troubles and issues to the wider world that God loves so much. It is a peace that empowers us to long for what God cares about and to engage with God in loving the people in our hurting world.

Today is the World Day of Social Justice, and I invite you to consider the connections between your prayer life and your availability to God.

- In what ways does your prayer life help you listen to God and engage with God’s priorities in the world?

- How does listening to God speak to you of social justice?

- In what ways does prayer help you engage with God’s priorities and call you to action on behalf of the poor and marginalized?

This post is excerpted from Joy Together: Spiritual Practices for Your Congregation by Lynne M. Baab.

This reflection is excerpted from the book, Belonging and Becoming: Creating a Thriving Family Culture, chapter 3, A Thriving Family Finds Its Rhythm.

I like to know what to expect and what’s expected of me. I like getting new calendars, making to-do lists and reading course syllabi. Although I don’t always come off as the most tidy and organized person (my room is usually cluttered, my sleep schedule is unpredictable), I love having expectations that I feel confident will be met.

When I was growing up, our weekly and daily family rhythms were a source of stability. I knew to expect to have dinner together unless other plans were made in advance. I knew that on Thursday nights we’d have Dad and Kid Night, while mom went out and got a break. I knew that on Friday nights we’d all eat pizza and watch a movie and that on Sunday nights we’d check in as a family.

When I was growing up, our weekly and daily family rhythms were a source of stability. I knew to expect to have dinner together unless other plans were made in advance. I knew that on Thursday nights we’d have Dad and Kid Night, while mom went out and got a break. I knew that on Friday nights we’d all eat pizza and watch a movie and that on Sunday nights we’d check in as a family.

I could count on yearly traditions as well. I knew Mom would give us that day off of school for out birthdays, and we’d have breakfast in bed while we looked at baby pictures. I eagerly awaited the couple of weeks leading up to Christmas when we’d have Santa’s Workshop days when we made gifts for friends and family.

Having an established rhythm built trust within our family. We were expected to show up for the rhythms of the day, the week or the year, and we expected Mom and Dad to do their part in upholding the sacredness of our traditions and routines. These rhythms provided space and time for checking in, for celebrating, for learning or playing together, and for supporting each other through rough seasons.

As we have gotten older, the rhythms have shifted to accommodate our changing needs. We still check in as a family once a week, ask each other about the highs and lows of the past seven days and pray for whatever challenges each person is facing. Sometimes the check-in is rushed by the necessity of homework or other outside commitments, but knowing that we’ll all be in the same space soon, sharing about our lives, is comforting and valuable.

Rhythm is a powerful tool for ensuring that the way we choose to spend our time reflects what’s most important to us. During the school year, my rhythms are mainly based on my schoolwork, my family, my friends and maintaining my emotional/spiritual landscape – all things that are important to me. Truth be told, I don’t have this down yet. But due to our family practices, I have a solid framework for cultivating and striving for rhythms that will create space for the most important things in my life.

Hailey Joy Scandrette is Founder and Editor in Chief of Ignighted Magazine, an online magazine and community of people ages 18-30 seeking to follow the teachings and actions of Jesus through incarnational living. She is also the daughter of Mark and Lisa Scandrette, authors of Belonging and Becoming: Creating a Thriving Family Culture. This piece is excerpted from the book (pp. 78-79) in the chapter, “A Thriving Family Finds Its Rhythm”.

Hailey Joy Scandrette is Founder and Editor in Chief of Ignighted Magazine, an online magazine and community of people ages 18-30 seeking to follow the teachings and actions of Jesus through incarnational living. She is also the daughter of Mark and Lisa Scandrette, authors of Belonging and Becoming: Creating a Thriving Family Culture. This piece is excerpted from the book (pp. 78-79) in the chapter, “A Thriving Family Finds Its Rhythm”.

Slowly the snow is giving way to reveal the garden. It’s been a long winter, colder and snowier than normal, a stark contrast to the past several winters. Even as seed catalogues arrive weekly, it’s difficult for me to think about gardening when everything is cloaked in white.

Slowly the snow is giving way to reveal the garden. It’s been a long winter, colder and snowier than normal, a stark contrast to the past several winters. Even as seed catalogues arrive weekly, it’s difficult for me to think about gardening when everything is cloaked in white.

The warming shelter I help run is still open for another three weeks — four if the weather remains cold and wet — reminding me that even with this brief respite from the cold, winter is not over. The Indigenous people of Hood River Valley remind us not to plant crops until the snow has melted from Mt. Defiance, ancient wisdom calling us to tune our lives to the seasons of creation rather than the culture of hyper-productivity. We’re still in a season of rest.

“Gardening is a lot of work!”

We don’t often think of rest when it comes to the garden. In fact, I know several people who would rather have all grass, or even pave the yard to keep things really simple. I used to believe gardens were a lot of work. I would spend hours in the spring digging and turning the soil.

With sweat dripping from my brow while my glasses slipped down my nose, I would dig deep, often two feet down, to loosen the soil. I’d pluck every weed, every clump of roots left from last year’s crop, until I could rake the garden into a flat brown empty canvas ready for planting.

With sweat dripping from my brow while my glasses slipped down my nose, I would dig deep, often two feet down, to loosen the soil. I’d pluck every weed, every clump of roots left from last year’s crop, until I could rake the garden into a flat brown empty canvas ready for planting.

During the spring, summer, and autumn, I would be out in the garden pulling weeds for hours. The garden was neat and tidy. Nice straight rows of vegetables stood out against the rich bare soil that separated them. Ah, this is how a garden is supposed to look!

At certain times throughout the season I would grab my organic fertilizer and carefully apply it around the plants. They needed food, after all. I would also watch carefully for garden pests and spray them with neem oil or other organic pesticides. The garden was beautiful, but it took a lot of work!

Spiritual insights

Have you ever approached your spiritual life like this? It’s a lot of hard work! I need to do my morning devotions without fail. I need to keep an active prayer list of all the folks I’m praying for. I need to clear out my calendar so that I can attend every church service and event. I sweep my spiritual house clean and fill it up with busy work. On the outside my life looks quite spiritual. Some even admire me for my commitment and resolve. Inside I’m exhausted. Faithfulness is a lot of hard work, after all.

Learning from God in the garden

Over time I began to realize I had created a lot of work for myself in the garden. Even my organic gardening was more work than it needed to be. As I read about other approaches and watched the less tended parts of my garden, I began to see something amazing: sometimes things thrive best when you stop working against the natural rhythms created by God.

I quit digging up my garden. I discovered that when I didn’t disturb the worms and other critters in the soil, and when I didn’t pull out all the remaining roots and other food they thrive on, they did the digging for me! Not only that, they also provided rich nutrients for the soil.

I quit digging up my garden. I discovered that when I didn’t disturb the worms and other critters in the soil, and when I didn’t pull out all the remaining roots and other food they thrive on, they did the digging for me! Not only that, they also provided rich nutrients for the soil.

In the spring, I lightly weed just where I’m going to plant, and I pull out any noxious weeds that spread like wildfire. It doesn’t take long, and the only sweat I break is because the sun is beating down on me.

I’ve barely added any fertilizer in the past several years, opting instead for rich compost created in my worm bin and out in my compost heap. Almost all the nutrients in my garden are produced in the garden. When you allow it to live its natural rhythm it feeds itself! I work much less and enjoy much more.

Spiritual insights

Over the years I’ve wasted a lot of time trying to fit into spiritual boxes created by well-meaning folks but who didn’t really know me. We all have a kind of spiritual temperament, a natural rhythm and style that works well with how we were created. Morning devotions may be perfect for one person but a complete failure for another. Journaling might unleash deep spiritual insights for some, gardening for others, and long periods of deep meditation for still others. All of these are tools intended to deepen our relationship with God and one another, but they are not the purpose of our faith.

At the heart of permaculture is understanding the landscape. Where does the light shine and for how long during the day? Where does the wind blow? Where does the water naturally collect? Understanding our core spiritual rhythms and temperament is similar to understanding the way that our land responds to the rhythms of nature. Every person, like every physical space, responds differently.

There is a rich, self-sustaining spirituality inside each of us. The Holy Spirit is there to help us discover it. When we begin to work in harmony with how God created us and with God’s presence within us we discover our relationship with God is much smoother, much deeper, much richer, and much less frustrating than before.

- Do you relate to any of the things I’ve mentioned here?

- As you were reading, did other new insights come that you’d like to share?

- How familiar are you with our own spiritual landscape?

Below is a short video about a permaculture garden. This is a great introduction to what permaculture is and how it works. This is very similar to what I’ve done in our yard (though appropriate for our northwestern climate). An additional benefit which I didn’t anticipate: with less work and more time to enjoy, I’ve discovered the garden to be even more a place of worship.

As an Amazon Associate, I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links.

Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

When referencing or quoting Godspace Light, please be sure to include the Author (Christine Sine unless otherwise noted), the Title of the article or resource, the Source link where appropriate, and ©Godspacelight.com. Thank you!