By Lilly Lewin

Many of us who work in churches are exhausted the week after Easter. We’ve just worked many long days in a row, and led or planned for many services and activities all in preparation for the big Easter Sunday. And if you don’t happen to work for a church, you still have probably been super busy getting ready for family and friends to celebrate the Easter holiday, and probably very busy with school and sport activities for either yourself or your family members. Or maybe, it’s just work that has overwhelmed you so you are looking forward to a much needed nap on the couch Easter Sunday!

Today I want us to look beyond Good Friday and even beyond Easter Sunday.

I want to remind us that Easter is a Season of the Church Year, not just one day.

The Season of Easter is actually 50 days, That means we get to keep celebrating NEW LIFE and Resurrection, and keep the experience of this joy going way beyond Easter Sunday.

I am challenging myself, and you, this week after Easter, to find time to get outside and be with Jesus in Nature. Take the time to have a Sabbath day beyond Sunday. Take a mini retreat to restore and get refreshment. It may sound impossible, but take an entire morning off or part of an afternoon. If you have kids, find a friend who will babysit for you and then return the favor so he or she can also have time for a Sabbath or retreat time. Make space in your schedule to have time to just BE with God.

When we lived in Napa Valley, we hosted a gathering called “Time in the Vines” or “Porch Time.” We invited people to come spend the morning with us on our porch and in the vineyard where we lived being with God in nature. I would curate the reflection time and my husband Rob would prepare lunch for everyone. We would often listen to a passage from the Bible and then I would give people questions to consider while they were being quiet either sitting on the porch or walking out in the vines. This is one of the reflections we did during Easter a few years back.

Porch Time (Your Mini Retreat/Sabbath Day begins Here! )

Thanks for taking the time out to be still and just BE!

“God is the friend of silence. See how nature—trees, flowers, grass—grows in silence; see the stars, the moon and the sun, how they move in silence…We need silence to be able to touch souls.” Mother Teresa

Opening Prayer:

There is nothing more important than what we are attending to.

There is nothing more urgent that we must hurry away to.

We Wait on you God.

Your time is the right time.

We wait for You to make Your word clear to us.

We know that in time

and in the spirit of deep listening

and in quiet stillness

Your way will be clear. AMEN ( based on a prayer by Thomas Merton)

We are in the season of Easter…the days between the Resurrection and Pentecost.

Sometimes we forget that Easter isn’t just one day. Easter is a Season of the Church Year and the Season of Easter is actually 50 days long. That means we get to keep celebrating NEW LIFE and Resurrection and keep the experience of this joy going way beyond Easter Sunday.

Sit and Look and Watch or Take a Walk and Look for “ Little Easters.” Joy Spots, Happy Places, and or Signs of Resurrection and New Life. Joyce Rupp calls the things we see and experience, the things that bring us new life and make us smile and hopeful

“Little Easters.” Today watch for these!

Allow God to talk to you through nature: the wind, the vines, flowers, trees, etc.

What newness do you need in your life right now? What kind of refreshment or resurrection?

Spend some time with that and talk to God…journal, walk, create something in art.

READ the Scripture 2-3 times and Listen

LUKE 24 the Road to Emmaus

13Now that same day two of them were going to a village called Emmaus, about seven miles[a] from Jerusalem. 14They were talking with each other about everything that had happened. 15As they talked and discussed these things with each other, Jesus himself came up and walked along with them; 16but they were kept from recognizing him.

17He asked them, “What are you discussing together as you walk along?”

They stood still, their faces downcast. 18One of them, named Cleopas, asked him, “Are you only a visitor to Jerusalem and do not know the things that have happened there in these days?”

19″What things?” he asked.

“About Jesus of Nazareth,” they replied. “He was a prophet, powerful in word and deed before God and all the people. 20The chief priests and our rulers handed him over to be sentenced to death, and they crucified him; 21but we had hoped that he was the one who was going to redeem Israel. And what is more, it is the third day since all this took place. 22In addition, some of our women amazed us. They went to the tomb early this morning 23but didn’t find his body. They came and told us that they had seen a vision of angels, who said he was alive. 24Then some of our companions went to the tomb and found it just as the women had said, but him they did not see.”

25He said to them, “How foolish you are, and how slow of heart to believe all that the prophets have spoken! 26Did not the Christ[b] have to suffer these things and then enter his glory?” 27And beginning with Moses and all the Prophets, he explained to them what was said in all the Scriptures concerning himself.

28As they approached the village to which they were going, Jesus acted as if he were going farther. 29But they urged him strongly, “Stay with us, for it is nearly evening; the day is almost over.” So he went in to stay with them.

30When he was at the table with them, he took bread, gave thanks, broke it and began to give it to them. 31Then their eyes were opened and they recognized him, and he disappeared from their sight. 32They asked each other, “Were not our hearts burning within us while he talked with us on the road and opened the Scriptures to us?”

33They got up and returned at once to Jerusalem. There they found the Eleven and those with them, assembled together 34and saying, “It is true! The Lord has risen and has appeared to Simon.” 35Then the two told what had happened on the way, and how Jesus was recognized by them when he broke the bread.

Things to Consider while Journaling:

• How do you recognize Jesus on the Road? What things help you to see him?

• What things keep you from recognizing Jesus? What things blind you to God/Jesus? And keep you from really seeing?

• The Two invited Jesus to stay with them, even though they didn’t know who he was. They practiced hospitality. How do you view hospitality today? Anyone you need to invite over?

• The Two on the Road were filled with grief? Any things or people you are grieving today? Talk to God about this. Allow God to love you in the midst of it.

• What things need to happen this week in order for you to feel like you see rather than be blind?

• What things need to happen in you in order for you to see Jesus rather than to be blind to Him?

• Notice the plant life…

Depending open where you live, what state or what hemisphere, what is growing? What is not? What is growing in you today? What do you want God to grow in you this Easter Season?

Take some time and talk to God about this.

——

I hope you have a wonderful Easter Sunday and feel the love and power of Jesus surrounding you. Remember to keep looking for

“LITTLE EASTERS,” “HAPPY PLACES” and/or “JOY SPOTS” beyond Easter and even beyond your mini retreat. Take the time to notice! Look and watch for things that remind you of resurrection. Look for and start watching for things that make you smile, laugh, or bring you joy! Keep a list of these things. You might even start a photo collection of these. Take a photo on your phone. Create a photo collage at the end of the day/week and post on facebook or instagram. Print out a copy of your joy spot photos to keep in your journal to remind you of how Jesus is blessing you! Remember to thank God when you recognize the joy spots and Little Easters along your way! And keep celebrating Easter all the way to Pentecost!

You want to hear about the Last Supper, do you? It’s a bit of a sore point for me, because I still grieve for the spiritually blinkered, inept disciple I was that night, and what I missed, hidden in plain sight. Having already proved myself to be impetuous in thinking I could walk on water like Jesus does, I became incredulous at the thought of him dying on a cross, never mind washing my grimy feet.

Yes, you heard that right. The God of the whole universe knelt at my soiled feet, tenderly washing and drying each foot as an act of supreme submission and love, when I should have knelt at His, especially after acknowledging Jesus as the Christ, Son of the living God.

I’d scoffed at first, dismissing washing feet as a weird idea for our revered Teacher to implement. Once I realised it was a sign of being united with Him, why I wanted to Him to wash so much more, of course—silly, wholehearted, young fool that I was! Now I’m amazed how blind I was to this act of sublime humility, little knowing just how much it would mean to me, and all it implied about God’s surrendered, sacrificial love.

I knew nothing of holy servanthood, whereby the path to the cross would be paved with stepping stones of love. I was ignorant of my own supreme arrogance in assuming I would remain loyal to the end and how, before many hours had passed, I would reveal myself to be a craven coward denying all association to my Lord.

These things still make me hang my head in shame. It’s a wonder and glorious act of grace that Jesus chose to reinstate me. Not only that, I gained a commission and a passion to live for Him to my own dying days, finally becoming a man who could be courageous.

We were sombre together that night, though we could barely comprehend what it would mean for Jesus to save us by dying an excruciating death on a cross. Our low mood was heightened by wondering which one of us would be capable of betraying Jesus, as He had suggested—an act so heinous we fearfully examined our hearts with a guilty conscience, aware of our own propensity for sin.

Later on, the bread and wine of our new covenant communion would take on special significance, reverberate with sacred awe and holy reverence, as we considered the beaten, bloodied, broken body of our Saviour crushed like pressed oil and grapes of wrath, made drink offering and manna bread for us, and all who would follow Him.

We would replay every moment of that last day and all that happened thereafter, cursing our own lack of awareness and culpability in contributing to putting Christ on the cross, while we wondered anew at God’s great, sacrificial gift to fallen humanity.

And as you know (for it’s a tale I’ve often told), extraordinary events followed hot on the heels of that night. Earth and heaven joined hands, were shaken to the core, with a tomb broken open by angelic means and the Lord Jesus Christ freed from death’s confines, raised for evermore.

Later, fearful, spineless disciples were turned into faith-filled, ardent apostles. But that’s a tale for another day. This is all you’re getting tonight, I’m afraid. Old Uncle Peter needs his rest. It’s time for sleep now. May your dreams be sweet, my friend.

**To read about the significance of Maundy Thursday, how it is named and celebrated differently around the world, please click here… **

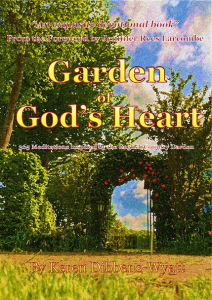

As regular readers know, many of us here at Godspace love gardens, and enjoy partnering with God in the process of helping nature bloom and thrive in our small plots of land. For a disabled person like me, unable to do any real gardening, my limited time outside has taken on a different form. It started as a seed of contemplation a few years ago, became a love of photography, and then both those things sprouted into a daily blog and thence into the leaves of a paperback book.

As regular readers know, many of us here at Godspace love gardens, and enjoy partnering with God in the process of helping nature bloom and thrive in our small plots of land. For a disabled person like me, unable to do any real gardening, my limited time outside has taken on a different form. It started as a seed of contemplation a few years ago, became a love of photography, and then both those things sprouted into a daily blog and thence into the leaves of a paperback book.

I spent some time each day prayerfully considering something I’d seen in a garden, mostly in the tiny one at the back of our rented home, or in my parent’s larger one when I went to stay, thinking about what it spoke to us of its creator. I found the most magical truths came out of these times: scriptural metaphors, such as a sparrow swooping under the watchful eye of God, or the clothing of lilies in splendour; scientific discoveries, like the fact that a snail can rebuild its shell when it is broken, or that a shield bug goes through several different instars or incarnations before reaching adulthood, and most of all, deep, resonating wonder at the sheer inventiveness and beauty all around us. Previously unconsidered items like compost heaps and barbecues, hoses and bird droppings, became food for thought and meditation. To my surprise, they yielded still more fruit for pondering.

I began to write them down, one source of inspiration each day. I loved creating poetic prose to go alongside my photographs of nature, and felt God prompting me to continue and to keep digging deeper in his rich soil. The results of my labour were not your usual gardening fare; no vegetables, herbs or flowerbeds sprang up. Instead, a book of 365 meditations was germinating. After roping in photographer friends and searching painstakingly through copyright free sites to make sure each entry had an apposite image to accompany it, the job of editing, pruning and proofreading began. After several years’ work, this Garden of God’s Heart is now ready to be picked off the shelf, and eaten with glee.

I hope very much that readers will savour the words and pictures that can take them through a whole year of devotions, and find it is a treasure trove of a book, saturated with love for God and all his creations, including the smallest and most overlooked things, right in front of our noses. I hope too you will enjoy this little taster….

Day Sixteen: Ladybird

The scarlet and the black, your priestly cloak holds tight to cased layers of petticoat-wings, made of the finest dark lace. Your Catholic credentials borne further aloft by your association with Our Lady and the holy names you carry: our Good Lord’s wee beastie (lieveheersbeestje), Moses’ little cow, little messiah, Lady’s bird. Wrapped in Mary’s red cloak and decorated by her seven sorrows, you fall from a thorny crown of rose briars like a drop of blood shed for us.

The scarlet and the black, your priestly cloak holds tight to cased layers of petticoat-wings, made of the finest dark lace. Your Catholic credentials borne further aloft by your association with Our Lady and the holy names you carry: our Good Lord’s wee beastie (lieveheersbeestje), Moses’ little cow, little messiah, Lady’s bird. Wrapped in Mary’s red cloak and decorated by her seven sorrows, you fall from a thorny crown of rose briars like a drop of blood shed for us.

A Cardinal, crimson carrier of insect incense, you waft cheerfully up and away like a hovering brooch; terror of the aphid, protector of the rose, defender of the faith, leopard of the garden skies, emblem of my early childhood reading, friendly-faced defier of fire in nursery rhymes, up, up and away you zoom, my imagination soaring with you.

Extract from Garden of God’s Heart by Keren Dibbens-Wyatt, photo by kfjmiller on morguefile.com

“Garden of God’s Heart is a delightful collection of meditations from an English country garden. I love Keren’s poetic prose which invites us into the contemplation of God’s beautiful creation in fresh and insightful ways. Each phrase holds treasures of understanding that lingered on my tongue and in my thoughts, beckoning me to dig deeper and enter the Garden of God’s Heart. A refreshing and enjoyable book, not just for those who love gardens, but anyone whose senses are stirred by the fragrance of a flower or the beauty of a tree. ”

Christine Sine, author of “To Garden with God,” contemplative and gardener.

Garden of God’s Heart has a Foreword by Jen Rees Larcombe, is published by Migiwa Press and is available to buy at Amazon, Lulu and Barnes & Noble.

Washing the Feet – Jan Hynes – Used by permission

by Christine Sine

It’s just before the passover feast. Jesus is eating dinner in Bethany and Mary pours expensive perfume on his feet and wipes them with her hair. (John 12 & Mark 13). A few days later, at the last supper, it is Jesus down on the floor washing feet (John 13) This is something usually only done by a slave.

Maundy Thursday Foot washing

On Thursday we will attend the Maundy Thursday love feast and foot washing at our church. It is my favourite Holy week celebration. Yet as I read these two passages in preparation for our celebration it suddenly struck me – was Jesus washing of feet not just a proclamation of himself as servant of all but also an identification with the slaves, the condemned and unnoticed in our midst. Is it that he was saying I am just like that woman. Is it

He Qi: Woman anointing Jesus Feet.

I suspect that the memory of the woman anointing Jesus feet must have come to mind when he took up the basin and towel. Some were just as offended by his actions as they had been by the woman’s. And perhaps it was this juxtaposition that really brought home to Judas that Jesus sided with the poor and the outcast, not the rich and the powerful. Perhaps for all the disciples this was a moment of painful realization that Jesus was not going to proclaim himself as the kind of king they had been hoping for.

Have you ever reflected on this juxtaposition of Jesus having his feet washed with perfume and then a couple of days later turning round and washing his disciples’ feet? I would love to hear what you know about this or what images it creates for you.

by Christine Sine

It’s Holy week. Yesterday we progressed around the church with our palm fronds singing hosanna, reminding ourselves of Jesus triumphal entry into Jerusalem. From here we walk with Jesus towards the cross through what I have in previous years called the most subversive week of Jesus life. In the past I have said that Jesus walk through Holy week begins with this triumphal entry and ends at the cross.

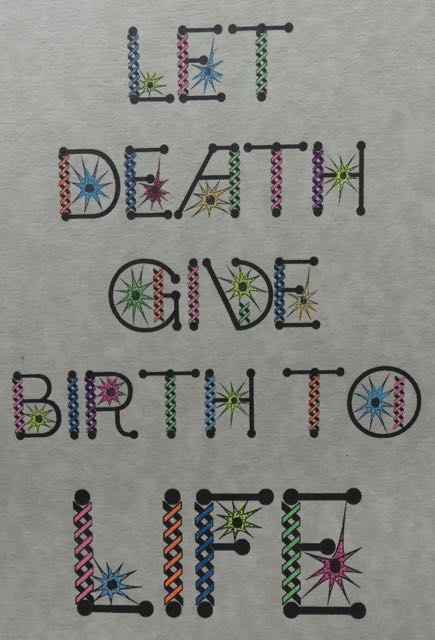

Today as I helped plant our spring vegetables, I was reminded that it does not really end at the Cross at all, it ends in the new life of the kingdom. It is very easy for us to get stuck at the cross, focus our attention on Jesus’ death and allow the true wonder of Easter to escape us.

Unless a grain of wheat is planted in the ground and dies, it remains a solitary seed. But when it is planted, it produces in death a great harvest. (John 12:24 The Voice)

Death gives birth to life. I don’t plant my seeds and then forget about them.

Are we stuck at the cross in the throes of death when God wants us to burst out of the tomb into new life? Are we stuck at the cross, unaware that the new life of the kingdom is bursting out around us?

Jesus endured the cross, he didn’t revel in it as we sometimes seem to. He looked ahead to the joy of a new world breaking into ours.

Don’t get me wrong. I love to walk the stations of the cross on Good Friday. I love to remind myself of the agony that Jesus went through in order to break the bonds of sin to bring us all to freedom, but I don’t want to stop there. I don’t want to live there in the heartbreak and despair.

The joy of Easter is not Good Friday, but Easter Sunday. This is the end of Jesus subversive walk. This is the place we are meant to live. Not on the cross, not in the darkness of the tomb but in the liberating light of God’s new world.

I want to enter into the new life of God, and bring that newness into the lives of those around. I want to see it burst forth into the creation that is still waiting with groaning, looking forward to the day when it will join God’s children in glorious freedom from death and decay. (Romans 8:21, 22)

Easter Sunday ushers in 50 days of celebration of resurrection life but for most of us by the time the sun sets on Easter Sunday we seem to have forgotten about it completely. We are back to life as usual, just as the disciples were.

In Acts 10:39-42 we read

“And we apostles are witnesses of all he did throughout Judea and in Jerusalem. They put him to death by hanging him on a cross, but God raised him to life on the third day. Then God allowed him to appear, not to the general public, but to us whom God had chosen in advance to be his witnesses. We were those who ate and drank with him after he rose from the dead. And he ordered us to preach everywhere and to testify that Jesus is the one appointed by God to be the judge of all—the living and the dead.

The Cross, the empty tomb are not the important events of Easter, the living presence of God in the resurrected Jesus is. It wasn’t the empty tomb that transformed the disciples and the women who followed him, it was Jesus appearing to them, eating with them, interpreting the scriptures for them. They met the risen Christ in the 50 days after Easter, and it changed their lives so that they went out not just talking about the things Jesus did, but living them.

What Is Your Response?

My challenge to all of us today is: will we hang around long enough to enter into the full joy of the risen Saviour? Will we hang around long enough to encounter the living Christ? When Easter Sunday is over will we be back to life as usual or are we ready to encounter Jesus over the next 50 days, which is the true season of Easter, and have our lives radically changed and redirected as a result?

Watch the video below and think about how during this Holy week you can get ready to “light the world” in the coming days.

“It is ourselves that we must spread under Christ’s feet, not coats or lifeless branches or shoots of trees, matter which wastes away and delights the eye only for a few brief hours. But we have clothed ourselves with Christ’s grace, with the whole Christ-“for as many of you as were baptized into Christ have put on Christ-so let us spread ourselves like coats under his feet.” ~Andrew of Crete 8th c

Not fig leaves or animal skins, desperately sown

after eating forbidden fruit, to cover our sin and nakedness.

This time it’s God’s Lamb shedding his blood,

giving his life, for the life of the world.

Riding on a donkey’s back

Jesus, our King and Savior,

triumphantly enters Jerusalem.

Those who line the way, caught up in the moment,

spread coats and lifeless branches under his feet.

Joyfully proclaiming,

“Hosanna, blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!

–the king of Israel!”

It’s different this time…

no animal skins to cover our nakedness…

no palm branches, coats or cloaks

to throw under his feet.

We, the baptized, are clothed with Christ’s grace,

unmerited favor and mercy,

dressed finer than even the wildflowers.

Called to put on the whole Christ

summoned, if we will, to spread our whole selves,

not coats or lifeless branches, costing nothing, under his feet.

Clothed with the whole Christ, made new,

we commit ourselves, like him,

to God’s way, acquiesce to God’s will,

and in doing so find peace, joy, purpose.

“ Let us spread ourselves like coats under his feet”.

As an Amazon Associate, I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links.

Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

When referencing or quoting Godspace Light, please be sure to include the Author (Christine Sine unless otherwise noted), the Title of the article or resource, the Source link where appropriate, and ©Godspacelight.com. Thank you!