Mary’s Act of Hospitality

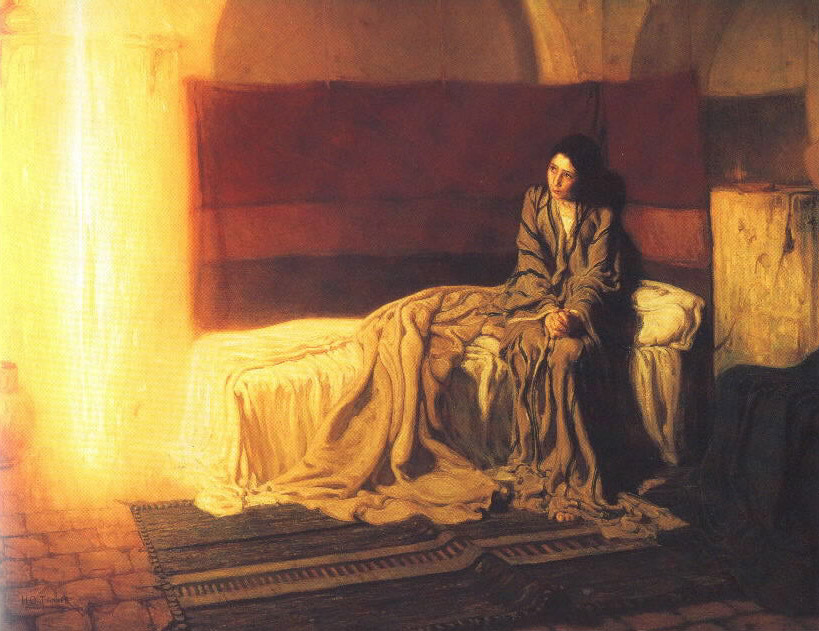

Let’s start with Tanner’s depiction of the Annunciation, where Mary looks, frankly, less than thrilled.

Luke tells the story, sourced presumably from Mary herself, years later, of Gabriel the angel bursting in on her with this announcement:

‘Mary, you have nothing to fear. God has a surprise for you: You will become pregnant and give birth to a son and call him Jesus.

He will be great,

be called ‘Son of the Highest.’

The Lord God will give him

the throne of his father David;

He will rule Jacob’s house forever—

no end, ever, to his kingdom.’

Mary knew her Scriptures. Check out the song she sings a few weeks later when she greets her cousin Elizabeth – she’s got some theological chops. I reckon she had a pretty good idea of what she was agreeing to. It’s an exciting opportunity, being part of God’s plan for redemption of the world. But perhaps Mary’s expression in Tanner’s painting reflects other knowledge she had.

Pregnancy is a dangerous business.

According to UNICEF, ‘women in the world’s least developed countries are 300 times more likely to die in childbirth or from pregnancy-related complications than women in developed countries’.

So if you, like me, live in a place with good healthcare for pregnant women and babies, you’ll need to imagine yourself a resident of rural Burma, or South Sudan, to understand what Mary was taking on – a pregnancy that was 300 times more dangerous than, for example, my current one.

According to the United Nations Development Programme:

‘South Sudan has the highest maternal mortality rate in the world – 2,054 per 100,000 live births. This is an astronomical figure representing a 1 in 7 chance of a woman dying during her lifetime from pregnancy related causes. Currently, there is only one qualified midwife per 30,000 people.’

First century Palestine was probably not so different from modern South Sudan in this respect. There would probably have been more midwives, but about the same level of modern medical resources like antibiotics, testing for dangerous blood pressure or gestational diabetes, and ultrasound scans.

In moments of logical thinking, Mary may have felt confident that her baby would survive – given his parentage and place in history – but no such assurance was given for her part in the story. Mary must have known of a great many women in her community who had died in childbirth or soon after.

Mary was probably also a teenager, which makes pregnancy even harder on the body and riskier. And even if she and her baby survived the next nine months, she was probably well aware of the discomforts – reflux, insomnia, swollen legs, sciatica, vomiting, back pain and more – and the dangers of bearing a child.

I think she knew what a dangerous task she was taking on – leaving aside for now any inkling of the grief that would later accompany her mothering – and she said yes with her eyes wide open. Hence the serious expression.

It was a generous act of hospitality to agree to carry and nourish Jesus in her body.

Here are Elaine Storkey’s beautiful words about this kind of hospitality:

‘Pregnancy is itself a symbol of deep hospitality. It is the giving of one’s body to the life of another. It is a sharing of all that we have, our cell structure, our bloodstream, our food, our oxygen. It is saying ‘welcome’ with every breath and every heartbeat. And for many mothers that welcome is given irrespective of the demands made on one’s own comfort, health, or ease of life. For the demands of this hospitality are greater than almost any of our own. And the growing foetus is made to know that here is love, here are warm lodgings, here is a place of safety. In hiding and in quiet the miraculous growth can take place.’

Welcoming the Unborn Child and the Vulnerable Parent

Wherever you live, unless it’s Scandinavia, you are probably surrounded by vulnerable women like Mary. Either you live somewhere with inadequate healthcare for pregnant women and babies, or you live in a first-world, socially-fractured community where the poor are getting poorer and children born into poor homes are much more likely than others to grow up in violence, neglect and dysfunction. Or both. Am I right about your situation?

An unborn child being carried by a mother in crisis or poverty or dysfunction is our neighbour in the same way as the man beaten by robbers in Jesus’ story of the Good Samaritan. What are our obligations of care and compassion for such children?

Just as Mary lent her own body to welcome the embryonic Jesus, we are called to sacrifice a measure of our own comfort and wealth to welcome vulnerable children and support their parents.

What can we do?

A clear consensus is emerging in the research. Early intervention in dysfunctional or under-resourced families brings the best results for building resilience in kids.

If we want to bring the kingdom to our local communities, and break the cycles of violence, neglect and poverty that exist in so many of them, perhaps the most strategic thing we can do is offer practical, meaningful support to pregnant women in crisis and vulnerable parents of young children.

This Advent, might the Holy Spirit be drawing you into a new step of radical hospitality? Could it be that God has people in mind for you to support?

Head to this post for a collection of ideas, some easy, some hard, that together could create an hospitable community where children grow up in supported and supportive families and the kingdom becomes more visible. Which ones are within your capacity this Advent or in the coming year?

Mary’s Son brought good news. We need no longer be disconnected and desperate. We who know her Son can bring light and love to all parents who struggle, if we decide to do so and are fuelled by God’s Holy Spirit.

This Advent, what hospitality is the Holy Spirit drawing you to offer?

———————————————————————————————————————-

Thalia Kehoe Rowden was a Baptist minister before the birth of her first child, in December 2011. Now anticipating the birth of a second December baby, she most definitely doesn’t want to be travelling on foot to Bethlehem or anywhere further than the kitchen, so feels a great deal of sympathy for Mary. She lives in Wellington, New Zealand, and writes at Sacraparental.

1 comment

[…] I wrote this week for Godspace, according to the United Nations Development […]