by Laurie Klein

Symmetry

A WOMAN BOWS over her potter’s wheel. She centers the clay’s ungainly heft, digs in her thumbs to create a hollow, then coaxes the sides upward.

Her work resembles a slender throat. Those of us watching marvel, the vase birthed like a song between two hands, almost godlike.

Then like a child toppling blocks, with one lowered fist—and a wink—she mashes the delicate lip. The opening warps. The walls cave.

Why raise up a vessel only to crush it?

Now the glistening folds of clay collapse. She flattens them into a spinning disk.

Thumping down fresh clay—on what is now a plate—she repeats the process, drawing the new walls high, then higher.

The wheel slows to a stop, and the deliberate weight of her finger against the lip forms a spout.

“Pressure facilitates pouring,” she says.

Reverently touching the flattened mass upholding the pitcher, she adds: “And this is foundational. The base determines the vessel’s outcome.” She looks at each of us, in turn. No winking now.

“Only the lowly in heart become godly leaders.”

The work of a saint

Today, as on every November 17th, many Christians celebrate a godly leader named Hilda, patron saint of learning and culture.

In 657 A.D., this grand-niece of Northumbria’s king embraced a daunting vocation: managing a co-ed monastery. Under Hilda’s guidance it became the leading abbey of the Anglo-Saxon world, and she, its revered abbess.

Hilda advised kings. She hosted the pivotal synod that determined the future direction of the English church. Five of the monks she mentored later became bishops.

And Cædmon, the abbey herdsman—aging, clumsy, tongue-tied, untutored—grew into his improbable name, which means poet.

A song in the night

During those times an abbey feast meant celebrants would perform a solo when the harp came their way. Ashamed to be song-less, illiterate Cædmon always fled.

One night, huddled in his bed of straw after yet another escape, he heard a voice in a dream: “Sing to me the beginning of all things.”

Cædmon opened his mouth to argue. Instead, out poured spontaneous words and a melody, addressed to the giver of songs in the night—the One addressed in Psalm 42:6. “Every day, you are kind, and at night you give me a song as my prayer to you, the God of my life.” (Contemporary English Version)

The next day the cowherd sang for the abbess.

A Slender Throat

Did he close his eyes? Did his throat go dry?

Abbess Hilda listened, astounded. Then she pronounced his song divinely inspired. To test his gift, she asked him to render a passage of sacred history into verse. After the monks explained it to him, he fulfilled the task.

Thereafter, the abbess encouraged the harp-dodger’s mystical, God-given skill. Uplifted by her patronage, his poetry flourished.

I picture Hilda’s support like a metaphorical plate beneath his unlikely pitcher: Cædmon the cowherd, destined to become the father of English poetry.

Today only one of his praise poems survives. Those words paved the way for later poets like Gerard Manley Hopkins, William Blake. In her poem, “Cædmon,” Denise Levertov writes: “[N]othing was burning, Cædmon cried out, nothing but I, as that hand of fire / touched my lips and scorched my tongue / and pulled my voice / into the ring of the dance.”

“Now we must praise”—that’s the opening line of Cædmon’s first poem. If he could address us today, perhaps that bashful man who hid from the harp might say, Cherish this world. Bless the Source.

Exalted or humbled, be the vessel uniquely raised up or brought down—consecrated to serve, ever-graced by God.

Dear readers, amid this culture of ours spinning out of control, may we likewise support, inspire, and hearten each other.

***

Cædmon’s Hymn (a modern translation)

Now we must praise the protector of the heavenly kingdom

the might of the measurer and his mind’s purpose,

the work of the father of glory, as he for each of his wonders,

the eternal Lord, established a beginning.

He shaped first for the sons of the earth

heaven as a roof, the holy maker;

then the middle-world, mankind’s guardian,

the eternal Lord, made afterwards,

solid ground for men, the almighty Lord.

In what way will you praise God today? Who will you encourage?

*****

The monk known as the Venerable Bede retells the story of Hilda and Cædmon in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People (731 A.D.). Fortunately, before an abbey fire almost destroyed this sole poem in existence today, someone copied the text. It’s now housed in the British Library. View a full set of images of the digitized manuscript here (click to page 5).

Click here for a dramatized video starring St. Hilda and the Legend of the Snakestones. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FMQsU1oYKWM

Other sources:

http://www.sthildasacc.org/about-us/who-was-st–hilda-of-whitby.html

https://imagejournal.org/article/caedmons-hymn-the-first-english-poet/

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/whitby-abbey/history-and-stories/caedmon-poetry/

As an Amazon Associate I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links. Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

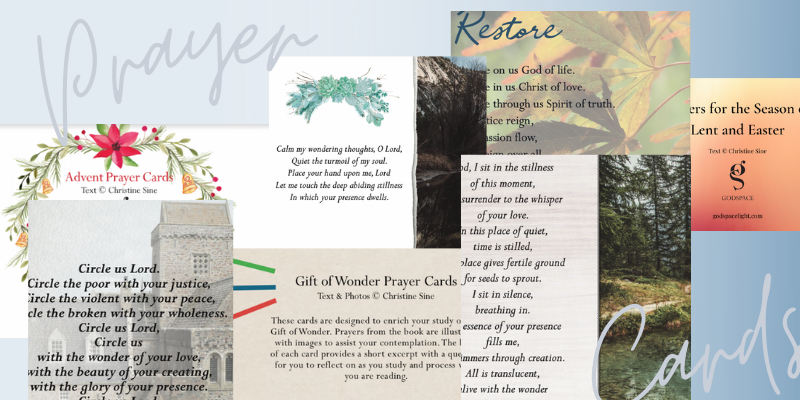

Prayer cards are available in the shop for many occasions and seasons–from everyday pauses and Lenten ruminations to breath meditations and Advent reflections, enjoy guided prayers and beautiful illustrations designed to delight and draw close. Many are available in single sets, sets of three, and to download–even bundled with other resources!

Prayer cards are available in the shop for many occasions and seasons–from everyday pauses and Lenten ruminations to breath meditations and Advent reflections, enjoy guided prayers and beautiful illustrations designed to delight and draw close. Many are available in single sets, sets of three, and to download–even bundled with other resources!