“Do what the priest tells you!”

That was my Irish Catholic family’s policy for most of my childhood.

Things didn’t go well when I wanted to start reading the Bible for myself.

The priests warned me that the Bible was dangerous and that I shouldn’t read it on my own.

“Just listen to the Homily in church each Sunday, ” they assured me.

If there’s one thing American evangelicals get jumpy about, it’s any hint that someone is trying to the take the Bible away from them. These Catholic priests committed an “American evangelical mortal sin.”

After years of these attempts to control my Bible reading habits, I rebelled… by reading the Bible on my own. In the fallout of that decision, I left the Catholic Church for good and sought refuge in the Wild West of American evangelical Christianity.

During those years, I threw myself into service, mission, Scripture study, activism, and any other evangelical endeavor presented as authentic action for the truly committed. No matter how ineffective my work appeared, how much I struggled to become “pure” and “holy,” or how much I endeavored to be an influential culture warrior, I failed to ask if my foundational beliefs and practices were problematic.

Looking back now, I see that I made the mistake of trying to transform culture without first being transformed into someone worth imitating or able to offer something truly transformative.

Eventually, the fire of fighting spiritual battles faded for me, and the pursuit of God became deeply frustrating. I was left with only the hollow shell of my arguments and fears, and I lacked the substance of connection, let alone union, with God.

My evangelical anxiety peaked while in seminary.

At the end of my coursework I dropped my seminary diploma onto a dusty pile of theology books and realized that I had no idea how to pray. In retrospect, I realize now that I could exegete Scripture in the original languages, but I didn’t have words to pray. (Little did I know, I wouldn’t need many anyway.)

Then one day, a pastor I knew from one of my seminary classes invited me to his new prayer service. This was back when all the cutting-edge evangelicals were experimenting with liturgy, candles, prayer books, and in the extreme cases, art.

This pastor didn’t strike me as the type to jump on a trend. I think he genuinely wanted to figure out ways to make church meetings more meaningful and to provide a deeper connection with

God. Reluctantly, I agreed to show up.

Liturgy, chants, and candles were the last thing that I, as a former Catholic, wanted out of church. But I was desperate to prove to myself that I was still a Christian and to prove to myself that God is real.

If anything, attending the service felt like a huge step backward. Evangelicalism was supposed to be my savior, the thing that rescued me from the seemingly lifeless liturgy of my Catholic days.

The whole service was completely unlike anything I had experienced as either a Catholic or an evangelical.

We chanted about God’s love.

We spent time centering on the Jesus Prayer.

We meditated on Scripture using the slow reading practice known as lectio divina, which helped us pray the words of Scripture.

Throughout the service I kept worrying that I was doing it wrong and wondering why I wasn’t having an encounter with God. It didn’t seem to be working. Either I was hopelessly broken or God wasn’t real. I returned home defeated, and I plunged deeper into my spiritual despair.

Yet in the following days, months, even years, I found myself returning to those prayer practices. Perhaps the connection they provided with God was something other than the FLASH, BANG!!!! conversion experience I’d been taught to expect among evangelicals.

Little did I know, this pastor had sown the seeds for my spiritual liberation from the anxious,

hardworking evangelical tradition. The practices in this underwhelming service would transform my faith, help me learn how to pray again, and help me rediscover the love of God.

The answers to my spiritual formation questions and my desire to find the love of God could be found in the writings and practices of the Catholic contemplative teachers who had been preserving variations of these spiritual practices for generations since the days of the Desert Fathers and Mothers.

The walls I had built against Catholicism as a Bible major at a Christian university and as a seminary student came crashing down as I learned the freedom and quiet of contemplative prayer practices.

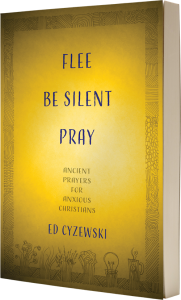

This post was adapted from Ed Cyzewski’s new book, Flee, Be Silent, Pray: Ancient Prayers for Anxious Christians.

This post was adapted from Ed Cyzewski’s new book, Flee, Be Silent, Pray: Ancient Prayers for Anxious Christians.

Ed Cyzewski writes at www.edcyzewski.com and at the Patheos blog: This Kinda Contemplative Life. He is the author Flee, Be Silent, Pray, A Christian Survival Guide, and other books. Connect with him on Twitter @edcyzewski and Instagram @edcyzewski.

Ed Cyzewski writes at www.edcyzewski.com and at the Patheos blog: This Kinda Contemplative Life. He is the author Flee, Be Silent, Pray, A Christian Survival Guide, and other books. Connect with him on Twitter @edcyzewski and Instagram @edcyzewski.