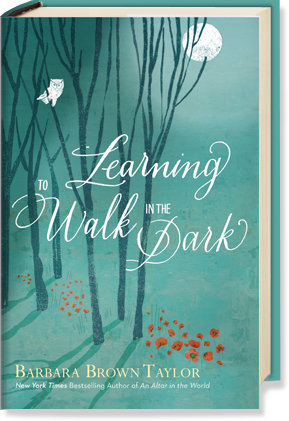

Yesterday’s post was inspired by my reading of Barbara Brown Taylor’s latest book Learning to Walk in the Dark an inspirational book in which she questions our tendency to associate all that is good with the light of day and all that is bad or evil with the darkness of night. She argues that we need to move away from our “solar spirituality” and ease our way into appreciating “lunar spirituality” (since, like the moon, our experience of the light waxes and wanes). Through darkness we find courage, we understand the world in new ways, and we feel God’s presence around us, guiding us through things seen and unseen. Often, it is while we are in the dark that we grow the most. Barbara explains:

The way most people talk about darkness, you would think that it came from a whole different deity, but no. To be human is to live by sunlight and moonlight, with anxiety and delight, admitting limits and transcending them, falling down and rising up. To want a life with only half of these things in it is to want half a life, shutting the other half away where it will not interfere with one’s bright fantasies of the way things ought to be. (55)

I have long been aware of how much more my own spiritual growth is accelerated by seasons of darkness. I know too that in the garden seeds germinate in the dark, and plants even grow more quickly at night then they do in the daytime. A rhythm of darkness, as I explained in a recent post Are You Getting Enough Sleep, is essential for us to function properly. And as I read Learning to Walk in the Dark I realized that it is even more essential than I thought.

I was particularly struck by the author’s recounting of the story Jacques Lusseyran, a blind French resistance fighter.

The problem with seeing the regular way, Lusseyran wrote, is that sight naturally prefers outer appearances. It attends to the surface of things, which makes it an essentially superficial sense. (105)

Our eyes skid over objects and glide quickly over things that we do not properly attend to. Being blind made him attentive to everything. And he noticed that when he was sad or afraid his inner light decreased. When he was joyful and attentive it returned. The best way to see the inner light was to love. In 1944 Lusseyran was captured by the Nazis and shipped to Buchenwald. He discovered that when he let himself become consumed with anger, he started running into or tripping over things. When he learned to love and live at peace with his circumstances, the inner light brightened and he could find his way without difficulty. As Lusseyran says:

If we could learn to be attentive every moment of our lives, he said, we would discover the world anew. We would discover that the world is completely different from what we had believed it to be. (106)

Learning to be attentive to all that is around us, is one of the challenges of life. Yet as Barbara Brown Taylor asks:

If you do not have the time to pay attention to an ordinary table, how will you ever find the time to pay attention to the Spirit? (106).

This has reinforced my desire to take time to notice. To run my hands over surfaces and allow them to speak to me. To listen to sounds that I usually ignore and hear what God would say through them. To inhale the aromas of God’s world and allow them to stir my spirit. This is my resolution for this year and this book has challenged me to pursue it.

2 comments

Thank you for this. My husband is an astronomer and spends many nights in the dark appreciating the splendor of the stars- this can’t be done in bright sunlight. Beautiful spiritual picture.

Thanks Carol, I love to gaze at the stars too and living in a city where there are always bright lights means that I have lost that opportunity. When we go to a place in the country, getting out to appreciate the night sky is one of the first things I like to do.