guest post by Elaine Enns and Ched Myers

Almost 60 years ago, America’s greatest prophet Martin Luther King, Jr. likened racism in our body politic to a lethal cancer. “The surgery necessary to extract it is complex and detailed. As a beginning we must X-ray our history and reveal the full extent of the disease.”

The murder of George Floyd reminded us yet again of how our society is haunted by endemic police violence past and present against black and brown bodies. So did the white supremacist riot at the U.S. Capitol on the Feast of Epiphany (indeed!). Nor would Dr. King have been surprised how our Canadian neighbors have just endured an excruciating summer of revelations, as ground-penetrating radar uncovered unmarked children’s graves at several former Indian Residential School sites across their nation, part of the legacy of Indigenous genocide that the U.S. fully shares.

When we peer beneath the surface of our white-settler lands, history, and culture, we indeed encounter ghosts. And the trivializing of this phenomenon by our Halloween-industrial complex cannot erase the fact that we live in a haunted house, which white denial and “agnosia” (willful or unknowing) have built.

Over the past quarter-century, “hauntology” has become a new social-psychological field of study about how the trauma of past oppression lingers in both people and places. Sociologist Avery Gordon, in her important book Ghostly Matters, contends that “haunting is a constituent element of modern social life through which repressed or unresolved social violence makes itself known in everyday life, especially when they are supposedly over and done with (slavery, for instance) or when their oppressive nature is continuously denied.” Gordon also emphasizes, however, that reckoning with these ghosts can mobilize “individual, social, or political movement and change.” But only if they are faced.

The Gospels portray the healer Jesus of Nazareth unmasking “unclean spirits” that lock people down. Sometimes they represent political “occupying powers” (as in the case of the “Legion” in Mark 5:1–20), sometimes personal forces of “possession” (as with a demon of silencing in Mark 9:17–29). One of Jesus’ strangest parables about the work of healing from such hauntings provides poignant illumination of King’s diagnosis.

When the unclean spirit has gone out of a person, it wanders through waterless regions looking for a resting place, but not finding any, it says, “I will return to my house from which I came.” When it comes, it finds it swept and put in order. Then it goes and brings seven other spirits more evil than itself, and they enter and live there; and the last state of that person is worse than the first. (Luke 11:24–26)

This may sound strange to modern ears, but it speaks to the complex stratigraphy of inward and outward hauntings that must be exhumed in the work of facing “the full extent of the disease”—its gravity, power, and permeation.

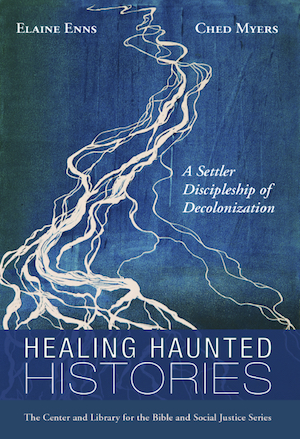

This parable strikes us as a trenchant diagnosis of the psycho-social geography of “possession-occupation” baked into a half-millennium of settler colonialism and racism, plaguing (in different ways) both inheritor-beneficiaries and victim-survivors of this system and its legacy. Indeed, this work is like peeling the proverbial onion seven layers down; the haunting of our psyches and spirits, our communities and culture, our public life and institutions, goes that deep. This is why the process outlined in our new book Healing Haunted Histories: A Settler Discipleship of Decolonization seems so daunting to us settlers of privilege, and why we avoid it at every turn.

But the gospels insist that Jesus wasn’t a socializing physician, patching people up to carry on with the status quo. Rather, he was a radical doctor who sought out the roots of our dis-ease. He offered strong medicine to treat the external oppression and internal psychosis of empire, which is why his healings were always disruptive of the status quo, earning him the ire of the authorities.

Responding to people in power who insisted there were no fatal flaws in their social-political-religious system, Jesus famously offered this koan: “Those who are well have no need of a physician, but those who are sick. I have come to call not the righteous, but sinners to repentance (metanoia, meaning to change fundamental direction; Luke 5:31–32). For the inheritors of white privilege, the greatest barrier to our liberation is our delusion of innocence. Only when we recognize the lethality of our dis-ease (to borrow from Twelve Step language) and turn to a Power greater than our own, will we be willing and able to turn our individual and communal histories around in the service of wholeness and justice, and to join with marginalized communities to heal our haunted bodies and body politic.

We long for our churches to become spaces that nurture the courage and competence to embrace a discipleship of decolonization, fueled by the prophetic hope that a day is coming when Creator will wither injustice to its roots, “until the sun of justice rises, with healing in its wings” (Mal 4:2).

Elaine Enns and Ched Myers codirect Bartimaeus Cooperative Ministries on unceded and untreatied Chumash land in the Ventura River Watershed of southern California. Healing Haunted Histories was published in February 2021 (see here for reviews, programs and discounts).

As an Amazon Associate I receive a small amount for purchases made through appropriate links. Thank you for supporting Godspace in this way.

Celtic Prayer Cards include 10 prayers inspired by ancient Celtic saints like Patrick or contemporary Celtic writers like John O’Donohue. A short reflection on the back of each card will introduce you to the Celtic Christian tradition, along with prayers by Christine Sine and beautiful imagery crafted by Hilary Horn. Celtic Prayer Cards can be used year-round or incorporated into various holidays. Available in a single set of 10 cards, three sets, or to download.

Celtic Prayer Cards include 10 prayers inspired by ancient Celtic saints like Patrick or contemporary Celtic writers like John O’Donohue. A short reflection on the back of each card will introduce you to the Celtic Christian tradition, along with prayers by Christine Sine and beautiful imagery crafted by Hilary Horn. Celtic Prayer Cards can be used year-round or incorporated into various holidays. Available in a single set of 10 cards, three sets, or to download.